Taste 165 Years of Tradition at a Sake Brewery

If you're a sake lover, you've got to make your way out to Fukushima for this amazing brewery with 165 years of history in every sip.

By Kim Yanghyeon

Sake Competition is an event that began with the idea of: “proposing new criteria, without regard to brands, for consumers to encounter truly outstanding sake.” The event, now in its sixth year, drew a total of 1730 sake entries from 453 brewers for its 2017 edition. The sake entries were separated into categories by variety and assessed by a panel of judges from all over the world in May 2017. For the fifth year running, Fukushima Prefecture took more first-place prizes than anywhere else in Japan. After learning Suehiro Shuzo, in Aizuwakamatsu, Fukushima, took the top prize in the Junmai Daiginjo category, I went to visit Kaeigura, Suehiro Shuzo’s sake brewery with 165 years of tradition.

Aizuwakamatsu Station opened in 1899, which lends it an impressive historical air. From the station, Suehiro Shuzo’s Kaeigura is an approximate 7-minute ride on the city’s loop-line bus. There’s a bus stop right outside the brewery. Besides Kaeigura, which has been handed down through the generations for over a century, Suehiro Shuzo also has a plant fitted with modern equipment about 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) away from here. But to truly savor the brewery’s history and tradition, as well as its tasting-inclusive tours, I recommend visiting Kaeigura.

It’s late morning on a Monday and there is no shortage of visitors. At the entrance hangs a sakabayashi, a round symbol that has been hung outside sake breweries since the olden days. When new sake was made, green cedar leaves were shaped into a ball and hung out front. Around the time the leaves have dried and turned brown, the sakabayashi portends that the sake had matured and was perfect for drinking.

Here at Kaeigura, artisans have endured both pain and joy over the past century-plus crafting sake to make people say, “Wow, this is good!” after their first sip. Heading in, there are sake barrels at the entrance...towards the back and up the staircase to the second floor is the room where the head of the brewery stayed. The room has been preserved as-is and is now shown as part of the tour.

Shoji, the brewery manager, provided the explanations. “Junmai Daiginjo”...now that you mention it, that’s the sake my husband often asks me to buy. Nothing but well-polished rice is used. A high-class sake made from only pure rice: “Daiginjo.” This sake is, of course, also crafted from rice, but alcohol is added in order to boost the rich flavor of this high-class sake. My husband is no expert, but no matter where the sake is from, he insists that the hallmark of Junmai Daiginjo is its fruity aroma and always buys this particular variety. A sake from Suehiro Shuzo took top prize in the Junmai Daiginjo category at Sake Competition 2017, making it the best-tasting sake as selected by consumers.

Sake is made from rice, but I was surprised to hear that the perfect rice for making sake would not necessarily taste good when cooked and served at a meal. Just the opposite, even if you made sake from the brand of rice called Koshihikari, which is famous for tasting the best when cooked, it wouldn’t necessarily turn out to be the best-tasting sake. In Japan, the best rice for sake is called Yamada Nishiki. If the grains are polished down to just 35 percent of their original state, it is said to be the very best ingredient for making Junmai Daiginjo. The polishing technique is also something special, and the powder that results from polishing is sold at shops around the city as rice flour for making sticky rice cakes and bread. Indeed, not a single thing goes to waste!

This is where the sake at Kaeigura is fermented. The Toji, or master brewer in charge of making sake, decides everything on his own, creating the best environment for fermentation and, depending on the sake, spending anywhere from 20 to 35 days for the process.

It was fascinating to see places like this where, in the olden days, barrels made of wood were used to ferment the sake. Back then, fires were lit under iron kettles to steam polished rice, which was then put in the barrels with koji mold to ferment.

In those days, after the sake had completely fermented, the wooden barrels were taken completely apart and thoroughly cleaned. Manpower was needed for every step, as far as putting out the parts to dry in the sun, leaving little doubt that it was sake made with heart and soul. Such a process surely ensured the sake was quite a luxury item back then.

I headed upstairs to the second floor. The stairway to the second floor seen from the entrance...upstairs was where the head of this brewery once lived. There were times when making and selling such expensive sake, he was able to give his children a life of luxury. In order to teach them how much hard work went into making sake, regardless of whether they were sons or daughters, he is said to have put them to work in the brewery among a staff comprised entirely of men.

A painting that shows what the sake brewery looked like in those olden days. Like the custom in Korea, I imagined that women were absent in order to keep their “impurity” out (more on that later). Though it seems to have been because making sake was hard work for women, and if even one or two were on hand to make meals, it led to arguments among the men, who lived in close quarters over a period of several months. So, from the start, women were not hired. I just imagined how doted upon I would be had I been born the daughter of a sake brewer back then.

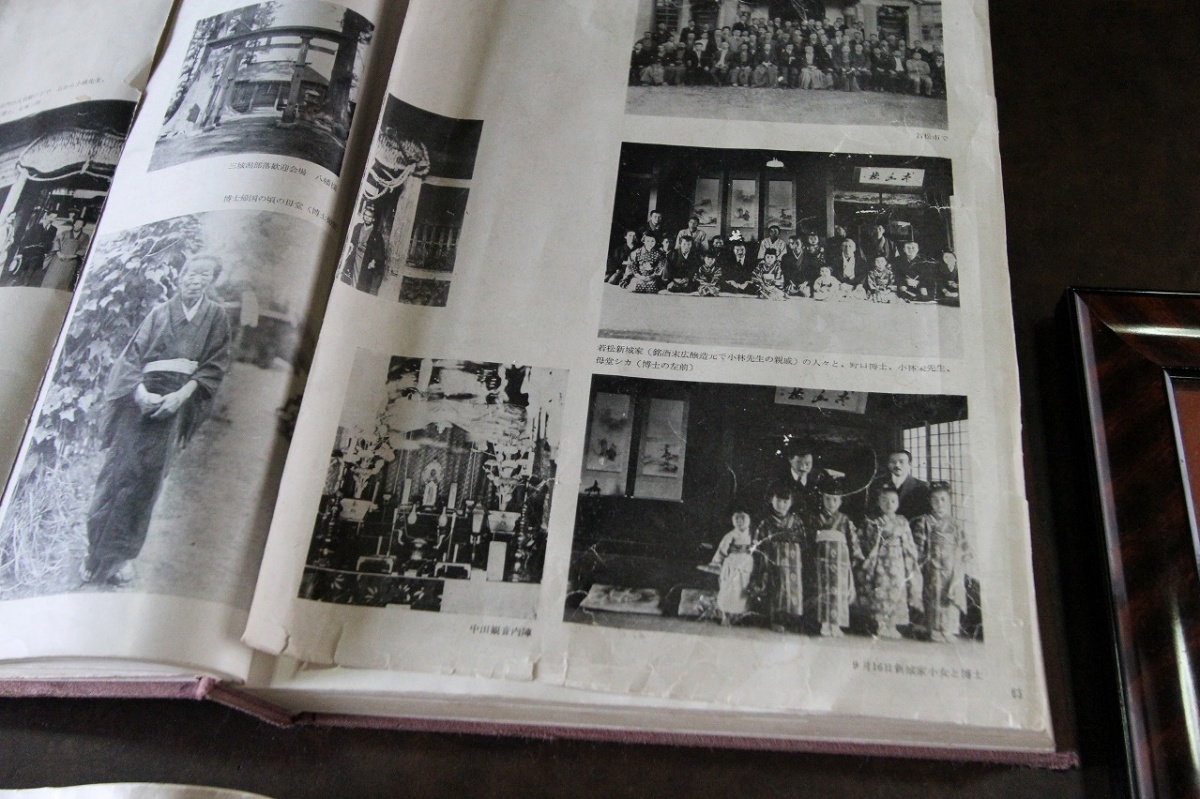

At Kaeigura, there is even a photograph of the brewery owner’s family together with Hideyo Noguchi, the world famous scientist who also graces Japan’s ¥1000 note.

Who would’ve imagined he would show up in a photo here? Noguchi was a native of Aizuwakamatsu and, as the head of the brewery in those days was good friends with him, is said to have visited often.

The tour over, I went down to the first floor for the tasting. Shoji, the brewery manager, poured me some delicious sake samples.

These are junmai-shu sakes sold only at this brewery.

The sake available here at Kaeigura is the kind overflowing with the devotion that you could only find in a place without modern equipment. Even people who, like me, do not have a taste for sake will get excited with a mere whiff of their utterly unique aromas. There was one sake in particular that caught my attention.

Junmai Daiginjo is a highly fragrant sake to begin with, but Suehiro Shuzo’s “Yume no Kaori” variety is, true to the Japanese name, fantastic for its dreamlike aroma. Normally, in a place like Korea, Japanese sake would be drank from a soju cup. But I think a better vessel for this Yume no Kaori would be a wine glass- it is simply so fragrant! I don’t drink all that much, but as someone who has enjoyed the particular aromas of the many Japanese sakes my husband drinks, I think I can say that I’ll remember this as the most special sake aroma I’ve ever experienced.

While it is an alcohol made from fermented rice, for me it is perfectly natural that this Yume no Kaori—true to sake’s English name “rice wine”—should be poured slowly into a wine glass, lightly swished, and drank while scrutinizing the aroma. Why not make the trip to Suehiro Shuzo’s Kaeigura in Aizuwakamatsu? This is where they make the best Junmai Daiginjo as recognized by consumers: Yume no Kaori. You may just encounter the aroma of your dreams.