How to Fix 7 Common Mistakes in Your Japanese

Here’s a list of seven Japanese nuances that foreigners frequently get wrong, as chosen by one of the reporters on RocketNews24's Japanese sister site. Keep in mind that these aren’t mistakes that would necessarily prevent you from being understood, but rather mistakes that, if you can fix them, will make you sound more like a native speaker.

By SoraNews241. Differentiating between 'wa' and 'ga' particles

http://en.rocketnews24.com/2015/12/12/seven-mistakes-foreigners-make-when-speaking-japanese-and-how-to-fix-them/

Non-native speakers often misuse wa and ga. Both are particles, meaning that they come after nouns in a sentence, wa marking the conversational topic of a sentence, and ga marking the grammatical subject.

Differentiating between the loose connection of topic and comment that wa gives and the solid connection of subject and predicate that ga gives can be very difficult for non-native speakers. But just that one particle can make all the difference.

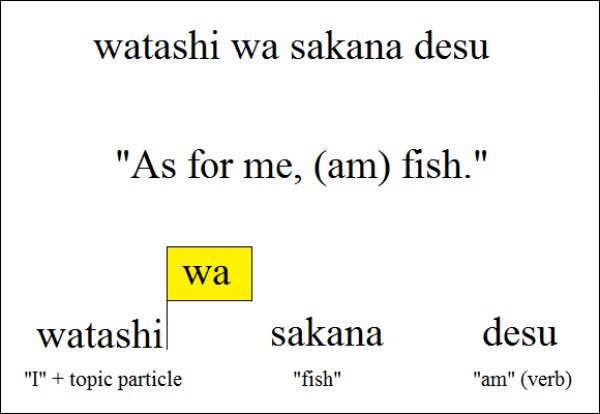

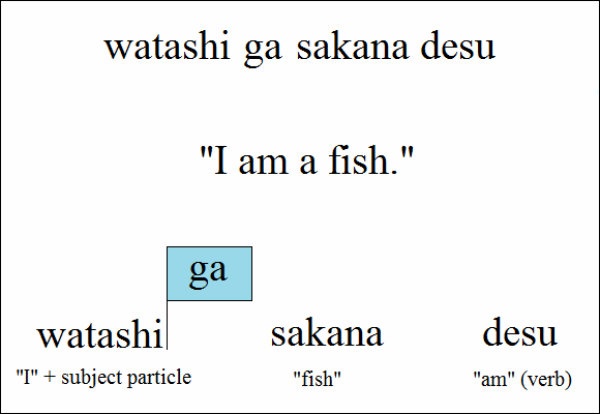

Let’s take a look at two sentences where the only difference is wa and ga. The particles are represented by flags marking the noun in the sentence.

Because of the loose connection between topic and comment that wa gives, this sentence has two possible meanings. The first one, above, is straightforward: (1) “As for me, I am a fish,” or simply “I am a fish.” However, in a different context, such as giving your order to a waiter at a restaurant, it could mean: (2) “I’ll have fish,” or “As for me, fish.” The topic and the comment are loosely connected by the wa, so the meaning depends on the context.

http://en.rocketnews24.com/2015/12/12/seven-mistakes-foreigners-make-when-speaking-japanese-and-how-to-fix-them/

In this sentence, watashi (“I”) is the grammatical subject marked by ga, so the meaning of the sentence is “I am a fish.” There’s no loose connection between topic and comment, just the solid connection between subject and predicate. If you were to say this one to your waiter, you’d probably get some strange looks.

One more note: ga can be used to zero in on the subject and exclude other possibilities. For example, if you were a fish, then you would introduce yourself using the standard, "Watashi wa sakana desu" (“As for me, I am a fish”). However, if you spotted someone wearing a fish-suit and wanted to declare that you, not the imposter, were a fish, then you would say, "Watashi ga sakaka desu" (I, not you or anyone else, am a fish).

With so many nuances and rules, making some wa and ga mistakes is inevitable. So don’t worry and just speak! It will take some practice and probably a few strange looks, but eventually your brain will sort it all out.

2. Honorific language

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fb/Himeji_Oshiro_Matsuri_Ju10_024.JPG

Rather than just switching around some words or using new expressions (which can also be done, of course), Japanese verbs conjugate into polite/honorific/humble forms. It’s almost as if rules dictated that you had to say “I eat fish” with your friends, “I eateth fish” with your boss, and “I forsooth-eateth fish” with the president.

The good news: the verb conjugations into the polite/honorific/humble forms aren’t that difficult. In fact, most people learn the polite desu/masu form first in Japanese since it’s a little easier than the casual forms.

The bad news: knowing when to use polite/honorific/humble language requires a whole new mindset. It’s easy enough to know that you should speak using polite desu/masu with your teacher or boss, but what about the more nuanced cases, like if you’ve grown close to a teacher/boss and don’t want to sound so formal, but still want to avoid being impolite? Do you speak using humble forms when meeting people for the first time, or will that come off as too distant and cold? At a business meeting, which side is supposed to speak using honorifics: the clients or the suppliers?

Thankfully, there’s more good news: even Japanese natives sometimes have difficulty keeping it all straight. Many companies give their new hires a training course in how to use honorific language properly, so if you’re ever in a position where it’s important for you to get it right, chances are someone will help you out.

Until that time comes, though, just keep this in mind: if you’re talking with someone to whom you’d say, “May I use the bathroom?” then stick with polite forms. If you’d say, “I gotta take a leak,” then feel free to let loose with casual forms.

3. Intonation

http://all-free-download.com/free-photos/download/megaphone_shout_action_219087.html

One thing that sets Japanese apart from other languages is the relative lack of intonation. Aside from the occasional pitch-accent, Japanese has no stress, no tones, and is mostly spoken in a “level” intonation. This doesn’t mean it’s spoken in monotone, just that individual words are spoken “evenly.” This can be a problem for speakers of English who are used to certain syllables in words having stress or more emphasis put on them.

For example, in the sentence we saw before, "Watashi wa sakana wo tabemasu" (“I eat fish”), often beginning Japanese learners will pronounce it something like: "waTAshi wa saKAna wo tabeMAsu," putting stress on all of the capitalized letters. This sounds very strange to native Japanese ears that are used to hearing the whole sentence spoken with the same intonation level.

To fix this, one thing we recommend is recording yourself speaking Japanese. If you have a favorite scene from a Japanese TV show or movie, try to recreate it yourself with your own voice, and record it. Listen to what you sound like compared to the original, and you may find that you’re carrying over some intonation habits from your native language that shouldn’t be there.