Driven Aloft: From Surgeon to Astronaut

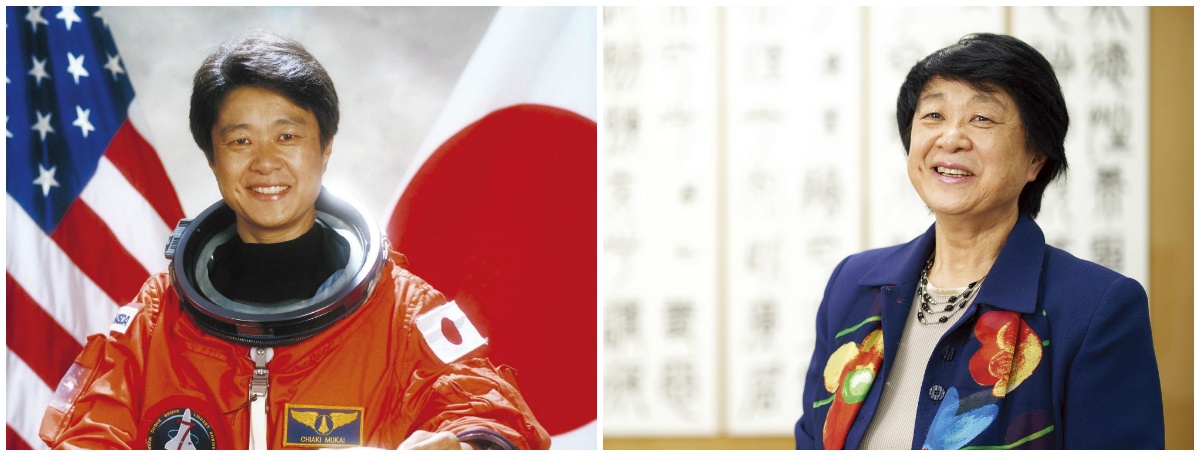

The Heisei Era (1989-) has been notable for Japan’s strides into outer space. Chiaki Mukai was the first Japanese female astronaut to join a space shuttle mission. Now the vice president of the Tokyo University of Science, she looks back on her career’s unusual trajectory.

By Highlighting Japan

https://www.gov-online.go.jp/eng/publicity/book/hlj/html/201904/201904_02_en.html

The Heisei years brought the birth of Japanese space exploration as well as the country’s first astronauts. Toyohiro Akiyama traveled to space in 1990, followed by Mamoru Mohri in 1992. Chiaki Mukai made history as the first Japanese woman to explore the cosmos aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia in July 1994 and again in 1998 aboard Discovery. Her leap from cardiovascular surgeon to space traveler created a lot of buzz at the time. In her current role as the vice president of the Tokyo University of Science, Mukai focuses on internationalization and the promotion of women in the sciences. “But I’m not Superwoman,” she says with a smile. “Becoming an astronaut was like winning the lottery several times.”

In the early 1980s, Mukai was working at Keio University Hospital, the first female cardiovascular surgeon to graduate from the hospital’s associated university. The National Space Development Agency of Japan, now Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), was focused on space shuttle research flights at the time, and was recruiting space technicians. Mukai thought, “This is my chance to see my hometown and Earth with my own eyes,” and applied. Although Japan had no equal employment opportunity laws, there was nothing written about the job being limited to men. Mukai was a hard worker full of curiosity, so much so that when her coworkers and superiors found out she’d applied, they simply remarked, “Of course, we knew it.” Mukai knew that all she needed to do was improve her physical strength and English-language ability. She powered up by swimming every day, and although she found English difficult she studied the language intensively. She finally succeeded in her quest, being selected for the program in 1985.

After the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986, however, the entire program went on hiatus, and Mukai’s training period was extended. “I lost friends on the Challenger,” Mukai says. “Watching the cutting edge of human technology turn into a giant orange ball of flames made my knees shake. It felt like a slap in the face for our human arrogance, placing too much faith in technology. If you look at satellite photos of the incident, all you can see is a little smoke above Florida. Looking up at something from below it seems so huge, but when you see it from the majestic expanse of space it seems minuscule. That shook me to the core, and certainly expanded my worldview.”

Mukai’s two spaceflights in 1994 and 1998 made use of her physiology expertise and medical experience. After that she was a visiting professor at the International Space University and a special consultant for JAXA. As Japan’s first female astronaut, she received a huge amount of attention, but says: “I never thought of it like I was participating as a woman or as a Japanese person. That was my way of creating an escape route. I’m the type of person who divides things in my mind into whether I can succeed at something or not based on my own hard work, not my background.”

Consistently bright and positive, her voice and attitude energize those around her. She jokes that since she has a medical license and flight experience but no money, she’d like to work as a tour guide for private flights to the moon.

“Heisei was a diverse age, and led to a plethora of new possibilities,” she concludes. “But we live in space, and Earth is very small when seen from the vastness of space. If humans don’t work hard to coexist happily, we’ll destroy ourselves. I hope the next era will teach people that.”