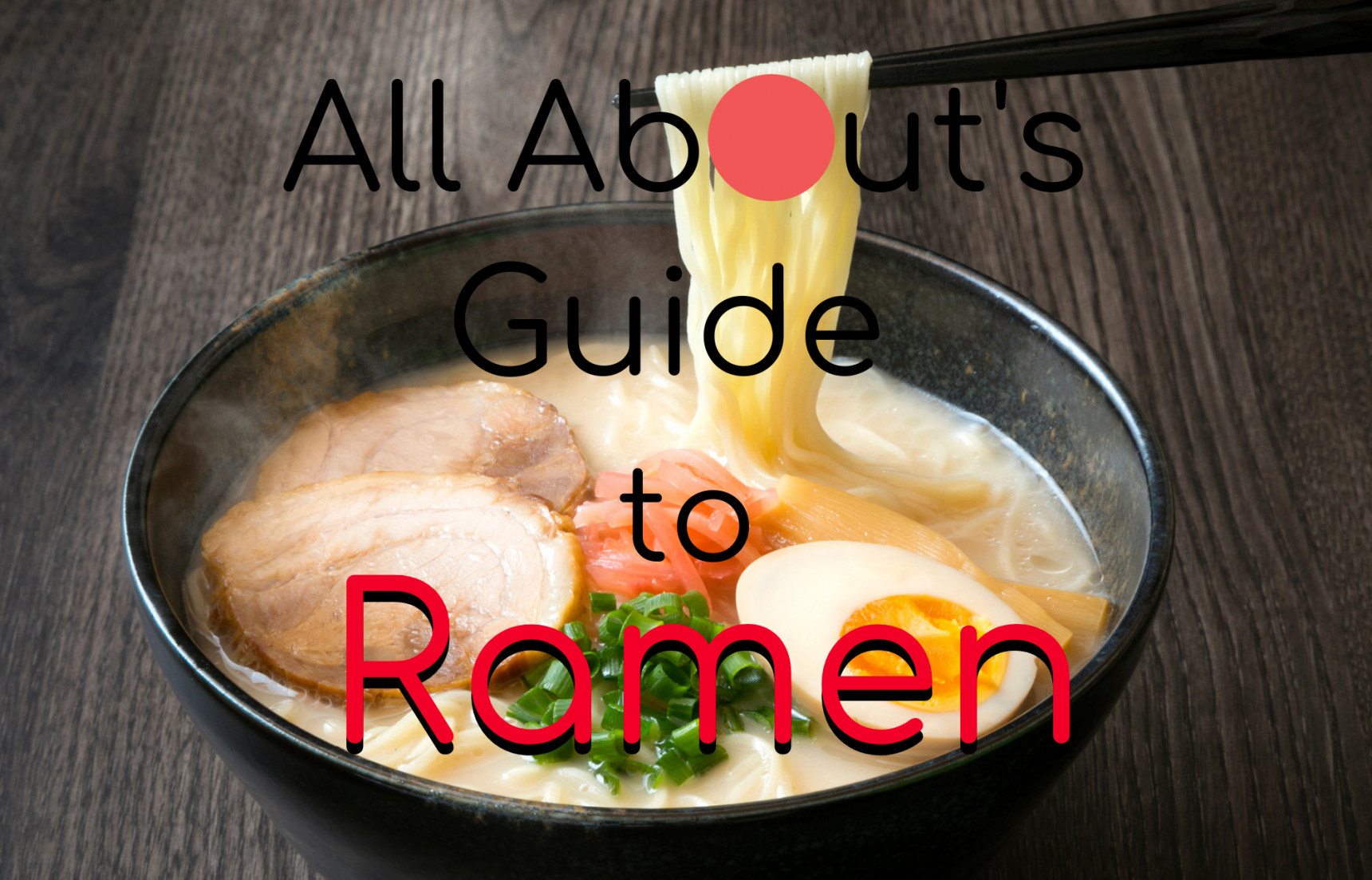

All About's Guide to Ramen

Ramen (ラーメン) is one of Japan's most beloved foods, and an iconic pillar of the country's acclaimed cuisine. This deceptively deep dish of noodles in broth sprinkled with toppings has captured hearts across the world, and often tops the list of food tourists entering the country. So let's dive into one of Japan's culinary national treasures.

By DavidHistory of Ramen

Pinpointing the date of ramen's first appearance in Japan has provided historians with some difficulty, made no easier due to the challenges faced in ramen taxonomy—what some consider to be a primitive form of ramen, others believe to be too detached from modern ramen to be given the same name. According to information found in the Shin-Yokohama Raumen Museum, some argue that ramen was eaten in Japan as early as 1485—based on excerpts from a renowned priest's journal (the Inryokennichiroku) in which he claimed to serve a Chinese ramen-like dish called "keitaimen" to his guests.

Another common claim is that the influential daimyo Mitsukuni Tokugawa was the first Japanese person to eat ramen. According to his journal (the Nichijoshoninnikki), he was offered a Chinese-style noodle dish by his Confucian friend, the Chinese exile Zhu Zhiyu in the 1690s. He liked it so much it was a recipe that he would later use to treat distinguished guests.

And others believe that we call ramen today, didn't actually exist until at least the late 1800s or early 1900s when soupy noodle dishes started to become more popular throughout the country. The origin of ramen in Japan may be up for debate, but one thing is for sure: ramen was originally a Chinese dish.

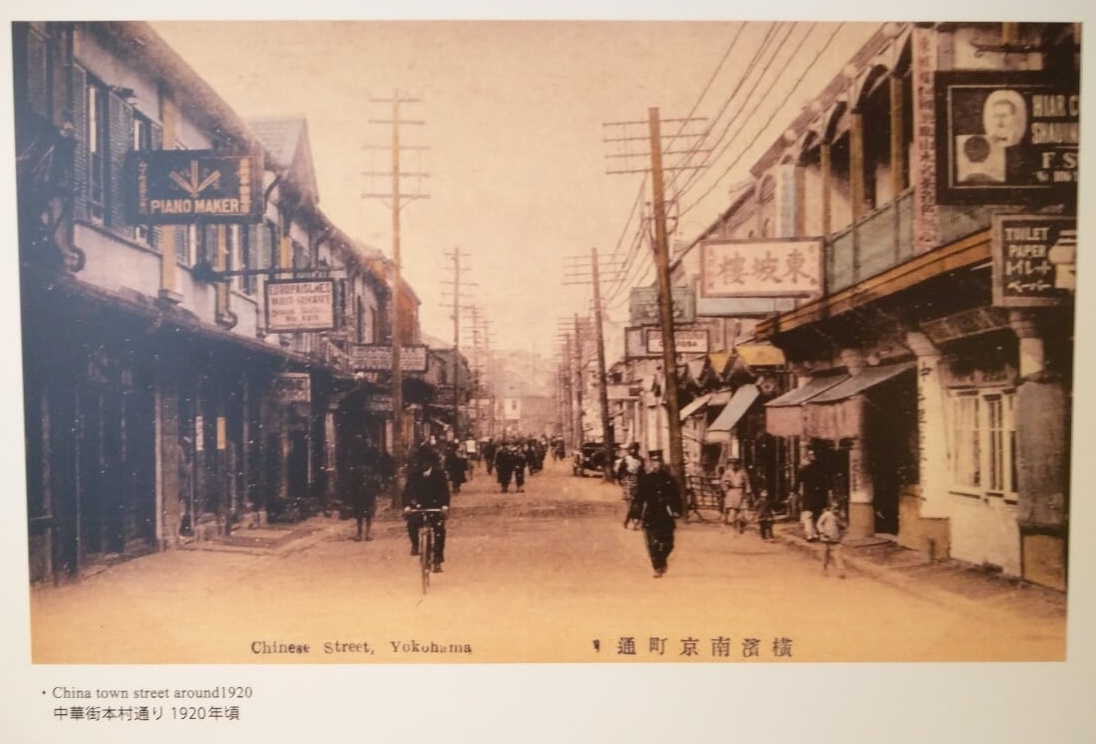

According to Modern Japanese Cuisine: Food, Power and National Identity by Katarzyna Joanna Cwiertka, the spread of ramen around Japan—and the subsequent changes (or "Japanization") that it went through before becoming the beloved dish it is today—happened after Japan opened its borders in the 1800s. In 1858 Japan signed the treaty of Amity and Commerce—following a 200-year period of national isolation, where almost no foreigners were allowed in Japan and no Japanese were allowed to leave. The following year in 1859, Japan opened its ports to foreign trade.

A by-product of this change in policy was never before seen numbers of immigrants and colonialists entering the country, especially in Japanese port towns. Since China was one of Japan's closest neighbors, the Chinese entered the country en masse, particularly as interpreters. Over time, the vast amount of Chinese living in Japan led to Chinatown-style areas, complete with Chinese grocery stores, Chinese tradesmen and Chinese restaurants.

One of the main dishes offered in these restaurants was Chinese soba noodles in soup, or Shina Soba, which was the precursor to ramen. Rairaiken opened in 1910 in Tokyo's Asakusa neighborhood, and is widely known as the first place to sell Shina Soba. It became one of its signature dishes, and so Rairaiken is regarded as Japan's first "real" ramen shop. Japanese people began to frequent Rairaiken and other Chinese restaurants selling the dish, and before they knew it they had succumbed to the Shina Soba fever. By the early 1930s (following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria and a disintegration in Japan-China relations) many Japanese cooks took over Chinese kitchens, at which point they started to embellish the dish with their own twists.

Shina soba eventually acquired the status of a "national" dish in Japan under a different name—ramen. Surprisingly, the name ramen came about in the '50s and '60s, following the surging popularity of a chicken-flavored instant version of the dish, which went on sale in 1958.

What is Ramen?

One of the main ways in which Shina Soba transformed into ramen was through the addition of an umami-rich broth, which now goes hand in hand with ramen. Umami (which was first identified by a Japanese scientist) is one of the five flavors detected by your taste buds—alongside salty, sweet, bitter and sour—and is the essence of that meaty or fishy taste that shines in ramen broth. While Chinese soba dishes came with a broth too, it was lighter, and used across a variety of other dishes in Chinese cuisine. Ramen broth, however, was made on more of an ad hoc basis, specifically as the base of a hearty bowl of ramen.

Ramen broths come in a variety of forms, from dashi (fish stock), miso or soy sauce to rich stock from pork or chicken bones.

Ramen's other central pillar is (of course) the noodles, and again these come in variety of forms depending on the ramen base, the region in which they're made and the culinary preferences of individual chefs and their target audiences. Ramen noodles made from wheat, brine, water, salt and eggs are generally categorized by their thickness, percentage of water used to make them, shape or waviness (chijire) and their color. Although the individual effects of any single ingredient may be subtle, the finished noodles are made to match particular types of soup.

But of course, no bowl of ramen would be complete without toppings! While there are no set rules for toppings, which are entirely at the discretion of chefs and diners, there are regional trends based on soup and noodle preferences. That said, there are certain staples that can usually be found in ramen around the country, including chashu (sliced pork belly), menma (seasoned bamboo shoots), spring onions, narutomaki (those swirl-patterned fish cakes), marinated soft-boiled eggs and nori seaweed.

Types of Ramen

Here's where things get a little murky. As previously mentioned, the classification of ramen can be a little difficult. Types of ramen vary from island to island, prefecture to prefecture (there are at least 30 distinct kinds of regional ramen) and even season to season. The aforementioned Shin-Yokohama Raumen Museum classifies Japanese ramen using three different scales—based on the soup, seasoning and "style."

Let's start with soup. The classification of soup depends on the base, with four main categories—tonkotsu (slow-boiled pork bones and fat), chicken, fish (dashi) and vegetable.

Then there's seasoning. Ramen can be classified by the main type of seasoning used in the broth. Ramen broths can contain anywhere from five to forty (!!) ingredients, and when you factor in the varying regions and local preferences, it starts to look as though there may be as many different types of ramen broth as there are ramen restaurants spread across Japan's islands.

So to narrow it down a bit, there are three main types of seasoning: shoyu (soy sauce), a shio (salt) and miso.

https://allabout-japan.com/en/article/5/

The last classification is by style. There are many different styles of ramen, and it's not surprising if most people aren't familiar with some of them. For example, there is tsukemen (dipping ramen—noodles with a thick broth served in separate bowls), mazemen (noodles and toppings without any broth), hiyashi chuka (a light cold ramen dish often enjoyed in summer) and tons of others from all around Japan.

Some of the most common include styles of ramen include:

・Sapporo ramen, topped with sweet corn, bean sprouts and local seafood in a miso broth.

・Kitakata ramen, with thick noodles in a pork and niboshi (dried sardine) broth.

・Hakata ramen (pictured above), with thin noodles in a tonkotsu broth, accompanied by an array of "exotic" toppings.

These are often referred to as "The Three Great Ramens of Japan." The last point to note is that the three classifications of ramen aren't necessarily exclusive from one another, meaning that finding a tonkotsu miso tsukemen (or any other wild combination) is a distinct possibility.

Ramen Etiquette

Now that we have more thorough understanding of ramen as a cuisine, let's look at how we tackle the ordering and eating of ramen when in Japan. People who are familiar with Japanese culture will know that etiquette is ubiquitous and of the utmost importance—this is also true for eating ramen.

One feature that is commonplace in many ramen shops—from those with hidden doorways in non-descript backstreets, to the brightly lit chain stores—is a vending machine which you use to place your order. At many popular spots around Tokyo, they'll have pictures or English because they're used to accommodating international clientele. But if you're at a particularly small or local restaurant, you'll unlikely to find pictures or English. But shop recommendations or specialties are often clearly indicated with a sign that reads "osusume," (お勧め・おすすめ・オススメ). Kore wa nan desu ka is another useful phrase (it literally means "What's this?") to learn, since even a single word answer like tonkotsu will let you know if you're on the right track.

You may even get lucky (such as in the photo above) with a sign stating something more obvious, like "No.1," which means that's probably what you should be ordering anyway! Just keep in mind that despite its cheap price (generally between ¥700 and ¥1,100), ramen can be a particularly filling food! There's no need to be too overzealous when it comes to ordering. Standard sizes often feel like they were at least a large once you've devoured them, and that's not even counting a side order of gyoza dumplings or a beer to wash it down!

Once you've successfully selected from the vending machine, you'll receive a ticket. If there's no line, you can take a seat at the counter, hand your ticket to a staff member and sit with bated breath while your meal is prepared. In most cases the food will be prepared somewhere behind the counter, so you can catch a glimpse of the chefs in action. When your ramen arrives, you will have two utensils with which to eat—a spoon for the broth, and chopsticks for the noodles and toppings. There are often extra condiments on the counter which you can add to your ramen. Feel free to use what you'd like, but be careful not to overburden your dish as it may cause offense to the chefs. Thankfully, eating ramen is a relatively shameless form of dining, so suckling, slurping and generally wolfing down your food are encouraged. Don't feel the need to hold back!

It's also worth mentioning that many restaurants are quite small. Be conscious of the fact that if you're dining with a large group, there's a very good chance you'll be split up for service.

Ramen Recommendations

It wouldn't be fair to call this a "guide" without a few recommendations on where you can sample different types of this delicious dish. Here are some of our favorite ramen restaurants around the Land of the Rising Sun.

Kageyama

Tokyo's Takadanobaba has no shortage of fine ramen shops, but my personal favorite is Kageyama. It's a thick chicken ramen served with lemon and rice. While the broth is like a thick chicken soup, the lighter toppings and lemon really brighten up the dish. It's perfect for summer!

Address: 1 Chome-4-18 Takadanobaba, Shinjuku, Tokyo 169-0075

Kikanbo

Kikanbo is a miso-based ramen chain with stores all over Tokyo (and a couple in China). Their most popular ramen is served with thick slices of pork belly, and for those who like their food to pack a punch, you can up the heat by choosing the degree of chilli and sichuan pepper in your meal.

Tomita

Tomita ramen in Matsudo (just outside of Tokyo) is famous across the country and the tonkotsu tsukemen (or tsukesoba) is widely regarded as the best there is. As such, waiting times can be at least an hour, and sometimes considerably more. But once you get a mouthful of that rich flavor, you'll understand that it was worth the wait!

Address: 1339 Takahashi Building, Matsudo, Chiba Prefecture 271-0092

http://www.ramenadventures.com/search?q=Tsuta

Tsuta

Tsuta in Sugamo, Tokyo was the first ramen shop to ever receive a Michelin Star, which is no small feat in a city with the most Michelin Star restaurants in the world. Their signature bowl is a shoyu ramen, made with soy sauce that has been aged for two years, along with soba noodles and other toppings. Wait times can be long, but Tsuta has developed a system; patrons get a ticket with a time slot on it after handing over a ¥1,000 deposit. When you return with your ticket, you're given your money back, which just so happens to be the price of a bowl!

Address: 1 Chome-14-1 Sugamo, Toshima, Tokyo 170-0002

Regional Ramen

It can be tough to get to every corner of the country to try its delicious regional ramen. That's why places like the aforementioned Raumen Museum are so awesome! Here are some other places where you can take a mini tour around Japan, from bowl to bowl.

Sapporo Ramen Alley in Hokkaido (pictured above) was the birthplace of the Island's acclaimed miso ramen, and is the largest ramen street in Japan. Here there are a litany of ramen shops were you can try this delicious miso based ramen, among many others. If you want a hearty bowl, this is where you'll find it!

Another great place to sample regional ramen is Kyoto Ramen Street, on the 10th floor of Kyoto JR Station. Here you can find eight fantastic ramen restaurants, all serving different kinds of regional ramen, including Bannai Shokudo, perhaps the most famous chain slinging Kitakata ramen.

http://afuri.com/menu/

Vegetarian, Vegan and Pescatarian Ramen

Although ramen is generally thought of as a meaty, umami-rich food, there are also plenty of options for vegetarians, vegans and pescatarians around the country. Afuri is classic example of this! Although their main dish is the popular yuzu (a Japanese citrus fruit) ramen, they also offer vegan ramen, which goes great with gluten-free noodles made from lotus roots!

For even more delicious options, check out the definitive Tokyo Vegan Guide!

https://allabout-japan.com/en/article/5203/

Something Different

If you're looking for something a little different you can try Menbakaichidai Fire Ramen in Kyoto, where they literally incinerate your ramen before your very eyes (all within the realms of health and safety of course), giving it a wonderful charred taste.

And for the more introverted eaters, you can check out the chain store Ichiran, which specialises in a Hakata-style tonkotsu ramen. In Ichiran the ramen is served to you in booths, where you don't actually have to come face to face with a member of staff.

Hungry for more? Check out All About's hub for all things ramen if you're still on the hunt for the perfect bowl!