12 Amazing Events in Japanese History

Human activity in Japan is estimated to trace back to around 30,000 B.C. While little is known of Japan’s earliest inhabitants, thanks to the introduction of Chinese writing in the fifth century, we do have extant written histories starting from the eighth century. Just for history buffs, here are 12 amazing events from Japan’s last 1,500 years!

By Michael Kanert1. Koreans Built Japan's First Temples (593)

https://pixta.jp/tags/%E5%9B%9B%E5%A4%A9%E7%8E%8B%E5%AF%BA?utf8=%E2%9C%93&page=1&sell_flat=1&rows=200&keyword=%E5%9B%9B%E5%A4%A9%E7%8E%8B%E5%AF%BA&exclude=&search_type=0&showDetailOn=true&option%5Bis_japanese%5D=&option%5Bshape%5D%5B%5D=&option%5Bmodel_re

The son of Emperor Yomei, Prince Shotoku (574-622) was a semi-legendary regent of the Asuka Period (592-710). He is credited with resuming contact with China and embracing Confucianism and Buddhism. Shotoku invited three carpenters from Baekje, a large kingdom encompassing the southwestern part of the Korean peninsula, to oversee the construction of Shitenno-ji (四天王寺), the first Buddhist temple in Japan, which began construction in 593 in what’s now south-central Osaka.

In 578, one of the three carpenters, Shigemitsu Kongo, founded the company Kongo Gumi, which contributed to both Nara's Horyu-ji Temple (now one of the oldest wooden structures in the world), and, almost exactly 1,000 years later, Osaka Castle, the mightiest castle ever built in Japan. Nearly 1,500 years after its founding, Kongo Gumi still exists today, and though it has operated as a wholly owned subsidiary of Takamatsu Construction Group since 2006, it is still largely recognized as the oldest company in the world.

2. A Japanese Woman Wrote the World’s First Novel (1010)

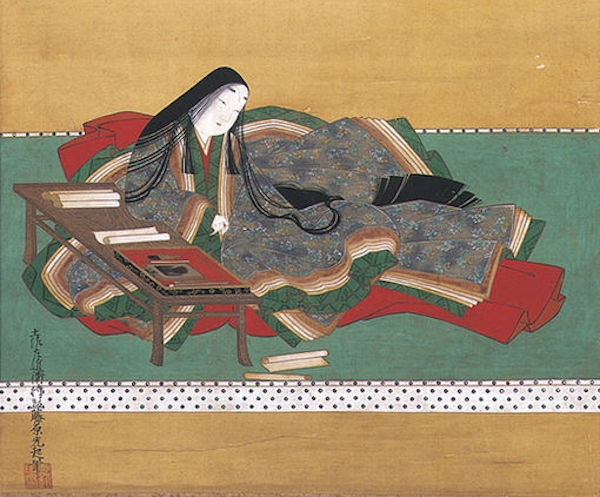

Completed around the year 1010, The Tale of Genji (源氏物語・Genji Monogatari) is generally considered to be the world’s first novel. It was written by a woman going by the pen name Murasaki Shikibu (c. 978-1014), though her real name is unknown. Born into a lesser branch of the powerful Fujiwara Clan, she served Empress Joto-mon’in in the court of Emperor Ichijo.

The Tale of Genji follows the (extensive) romantic exploits of Hikaru Genji, son of a fictional Emperor Kiritsubo and a low-ranking concubine, presenting a snapshot of the life and customs of Heian Period Kyoto (794-1185). In addition to prose text, the full version incorporates some 800 waka poems attributed to the amorous protagonist.

3. Benkei Died Standing (1189)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamoto_no_Yoshitsune

Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1159-1189) was a leader during the Genpei War (1180-1185), fought between the noble Minamoto (Genji) and Taira (Heike) clans. His chief retainer was Musashibo Benkei (?-1189), a fearsome warrior monk who joined Yoshitsune after the latter defeated him at a bridge in Kyoto.

Yoshitsune led his clan to a succession of victories, enabling his half-brother Minamoto no Yoritomo to become the first Kamakura shogun in 1185. After the war, however, Yoritomo became suspicious of his superlative half-brother, nullifying his titles and forcing him to seek refuge with the powerful Northern Fujiwara Clan. But Yoshitsune's patron died in 1187, and his son submitted to the demands of the new shogun and had Yoritomo's residence surrounded.

Benkei guarded the bridge to Yoshitsune's residence, where it's said he killed more than 300 men singlehandedly. Terrified to approach, the soldiers attacked from a distance with arrows, and though Benkei eventually stopped moving, still he did not fall. When at last the soldiers worked up the courage to come near, they found that Benkei had died standing on his feet. The event is known as Benkei no Tachi Ojo (弁慶の立往生), or the Standing Death of Benkei.

Yoshitsune, meanwhile, had committed suicide within his residence. He is symbolic of the tragic hero in Japan, a popular figure in kabuki, and the central character in the third section of the epic poem The Tale of the Heike (平家物語・Heike Monogatari), which recounts the events of the Genpei War.

4. ‘Divine Wind’ Repelled the Mongols (1281)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mongol_invasions_of_Japan

In 1274 and 1281, Kublai Khan sent two massive navies to conquer Japan after the Kamakura shogunate (1185-1333) refused to submit to his rule. An estimated 30,000 to 40,000 men were sent in autumn 1274, harrying the islands and northern coast of Kyushu. However, a typhoon struck as the Mongol ships anchored in Hakata Bay, sinking roughly a third of the fleet and sending the rest fleeing home—which was lucky for the Japanese, who had been largely overwhelmed by the Mongols’ unfamiliar armaments and tactics.

A second fleet, said to have comprised some 4,400 vessels and 140,000 men, came in August 1281. This fleet was hit by an even more powerful typhoon that drowned at least half the invading force and sank all but a few hundred ships. This second event gave birth to the term kamikaze (神風)—the “divine wind” that protected Japan. That said, the expense of preparing for the second invasion—including the construction of a 20-kilometer-long (12 mi) wall on the coast of Fukuoka—hobbled the shogunate, ultimately precipitating its decline.

5. A Tsunami Carried Away a Temple (1495)

https://pixta.jp/tags/%E9%8E%8C%E5%80%89%E5%A4%A7%E4%BB%8F?utf8=%E2%9C%93&keyword=%E9%8E%8C%E5%80%89%E5%A4%A7%E4%BB%8F&search_type=0

At a height of 11.3 meters (37.4 ft) and weighing in at 121 tons, the Great Buddha of Kamakura is Japan’s second-largest bronze buddha statue (the largest, Nara's Great Buddha, stands 14.98 meters/49.1 ft). It began construction in 1252 at Kotoku-in Temple (高徳院・Kotoku-in) in Kamakura.

While the Great Buddha was originally enshrined in the temple’s Daibutsu-den Hall, the hall was destroyed by a typhoon in 1334, and again in 1369. After the hall was destroyed yet again by a tsunami in 1495 (sometimes erroneously recorded as 1498), it was decided to just leave the Great Buddha in the open air—where it can still be seen today.

6. An African Samurai Defended Japan’s Greatest Warlord (1579-82)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_An0-cbZ60Q

In 1579, the Jesuit missionary Alessandro Valignano brought an African slave to Japan. Nobody is entirely sure where he was born, though it's been proposed he may have been from Mozambique, Angola or Ethiopia, or perhaps a European-born slave from Portugal. His real name, too, is unknown, but people in Japan called him Yasuke, which is believed to be the Japanese phonetic approximation of his original name.

Yasuke was called to an audience with Oda Nobunaga, the most powerful warlord of the day, who was so impressed by Yasuke's strength and size—recorded as roughly 188 centimeters (6ft 2in) tall—that he made him his personal retainer and bodyguard. In 1581, Yasuke was elevated to the rank of samurai and stationed at Azuchi Castle, Nobunaga's crowning glory, where he dined with the warlord and functioned as his personal sword bearer.

When Nobunaga was betrayed by Akechi Mitsuhide and forced to commit suicide at Honno-ji Temple (本能寺・Honno-ji) in 1582, Yasuke was there, and battled Mitsuhide's forces. He escaped to Azuchi Castle and briefly served Nobunaga's son until he, too, was attacked by Mitsuhide and committed suicide. Yasuke then surrendered his sword to Mitsuhide who, unaccustomed to a samurai surrendering rather than killing himself after the death of his lord, ordered Yasuke returned to the Jesuit mission in Kyoto. Thereafter, Yasuke's fate is unclear, though it's possible his presence was recorded around Kyushu in 1584.

7. Odawara Castle Fell to a Party (1590)

https://pixta.jp/tags/%E5%B0%8F%E7%94%B0%E5%8E%9F%E5%9F%8E%20%E5%8F%B2%E8%B7%A1?utf8=%E2%9C%93&page=1&sell_flat=1&rows=200&keyword=%E5%B0%8F%E7%94%B0%E5%8E%9F%E5%9F%8E+%E5%8F%B2%E8%B7%A1&exclude=&search_type=0&showDetailOn=true&option%5Bis_japanese%5D=&op

Oda Nobunaga had already unified the southern half of Japan by the time he was betrayed and forced to commit seppuku in 1582. His former sandal-bearer, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, picked up where Nobunaga left off, and by 1590, only the Hojo Clan stood in the way of a fully reunified Japan.

By this point Hideyoshi was so dominant that he didn’t have to attack the Hojo’s last stronghold at Odawara Castle: he just set 200,000 troops outside the castle gates and threw a three-month party, including concubines, prostitutes and even a mini-circus of acrobats, fire-eaters and jugglers, not to mention his personal tea master.

This isn’t to say Hideyoshi wasn’t brutal: shoring up the defenses at Odawara had created vulnerability at nearby Hachioji Castle, where Hideyoshi’s forces slaughtered so many people in a day the hillside is still thought to be haunted.

After three months of siege at Odawara, the Hojo Clan finally surrendered on August 4, 1590. Clan leader Hojo Ujimasa committed seppuku, and the castle was awarded to Tokugawa Ieyasu, who would ultimately reap the rewards of Hideyoshi's campaign by founding the Tokugawa shogunate in 1603, just five years after Hideyoshi's death.

8. Kabuki Was Invented by a Woman, then Taken Over by Men (1603)

https://pixta.jp/tags/%E5%87%BA%E9%9B%B2%E9%98%BF%E5%9B%BD?utf8=%E2%9C%93&page=1&sell_flat=1&rows=200&keyword=%E5%87%BA%E9%9B%B2%E9%98%BF%E5%9B%BD&exclude=&search_type=0&showDetailOn=true&option%5Bis_japanese%5D=&option%5Bshape%5D%5B%5D=&option%5Bmodel_re

In the first known record of kabuki in 1603, it was referred to as kabuki otori (かぶき踊 or かふきをとり), where kabuku is an old term meaning to lean or act strange, while odori (or otori) means dance.

The art form is credited to a woman named Okuni (お国), who assembled a traveling troupe that danced and acted—and engaged in prostitution. Kabuki quickly spread to red light districts throughout Japan, but problems with samurai fighting over their preferred performers led the government to ban women in kabuki in 1629—and then, when replacing women with young boys led to the same problem, boys were banned in 1652, resulting in the all-old-man kabuki we see today.

Unlike Noh, which was a ritualized, upper-class art form, kabuki was enjoyed by average people. Having developed into a more serious art over the years, kabuki is now written 歌舞伎, combining the kanji for sing, dance and technique.

9. 47 Ronin Spent a Year Plotting Revenge (1701-03)

Asano Naganori (1667-1701) was daimyo of the Ako Domain, which now comprises the cities of Ako and Aioi, as well as the town of Kamigori, on the southwestern edge of Hyogo Prefecture. When he was chosen to entertain imperial envoys in Edo (now Tokyo), he butted heads with protocol master Kira Yoshinaka (1641-1703), who was so rude that Asano finally drew his sword and wounded Kira. For his crime, Asano was ordered to commit seppuku and his clan was divested of its holdings.

47 Asano retainers, now lordless ronin, spent over a year preparing their revenge. Their leader, Oishi Kuranosuke, ostentatiously devolved into drunkenness, frequenting brothels and even divorcing his wife, all with the aim of getting Kira to let down his guard. When at last he did, the 47 ronin gathered and attacked his mansion on December 14, 1702, in the old lunisolar calendar (January 30, 1702, in the Gregorian calendar). One team beat down the front gate with a giant mallet, while another entered through the rear. 15 defenders were killed and 23 wounded, while the ronin sustained just two injuries—one of which was a sprained ankle. They found and killed Kira, then cut off his head and carried it to Sengaku-ji Temple (泉岳寺・Sengaku-ji), where their lord Asano was buried. They then turned themselves in.

Rather than being executed, the ronin were allowed to commit seppuku, thus restoring the honor of their lord’s family. Instantly becoming symbolic of samurai loyalty, they’re known in Japanese as the Shiju-shichi-shi (四十七士), while the surrounding events are known as the Ako Incident (赤穂事件・Ako Jiken). Their graves can still be seen at Sengaku-ji, located right beside Sengakuji Station on the Toei Asakusa Line. The story has been extensively dramatized in kabuki and other forms under the title Chushingura (忠臣蔵): Treasury of Loyal Retainers.

10. Gunboat Diplomacy Opened the Ports (1853)

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%BB%92%E8%88%B9

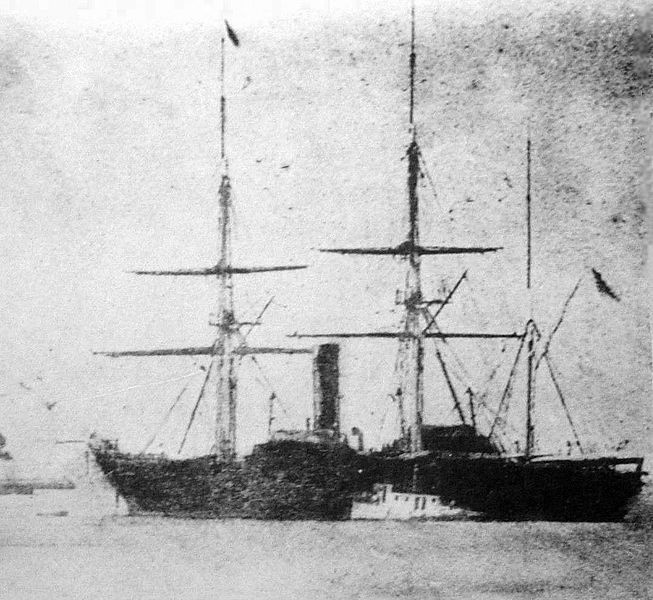

On July 8, 1853, Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry sailed his fleet of two steamers and two sloops—which the Japanese called “Black Ships” (黒船・kurofune) due to the black smoke the steamers spewed—into Edo Bay. While the isolationist Tokugawa shogunate had forbidden the construction of any ship larger than about 100 tons, the largest of Perry’s ships was 2,450 tons, and they came loaded with 73 cannons and some 1,500 troops.

Japan actually had a small complement of cannons of its own at this time, and trade with the Dutch in Dejima, Nagasaki—the only Japanese port open to just this one European nation—had enabled the shogunate to complete its first reverberatory furnace (a prerequisite for iron cannon construction) by 1852. But Edo’s defenses were still no match for Perry’s ships, and the shogun was forced to receive a letter from U.S. President Millard Fillmore demanding that Japanese ports offer supplies to America's burgeoning Pacific whaling fleet.

Perry promised to return a year later to receive the shogun’s response. He came back early, on February 8, 1854, now with seven ships, and a further two that arrived after he dropped anchor in Edo Bay. Thanks to this show of force, a treaty was signed on March 31, allowing American ships to dock first in Nagasaki, and later in Shimoda and Hakodate, thus ending the shogunate's Sakoku (鎖国) closed-country policy that had been in place since 1639, sending shockwaves throughout the nation.

11. Hidden Christians Kept the Faith for 200 Years (1650-1865)

https://pixta.jp/tags/%E5%A4%A7%E6%B5%A6%E5%A4%A9%E4%B8%BB%E5%A0%82?utf8=%E2%9C%93&page=1&sell_flat=1&rows=200&keyword=%E5%A4%A7%E6%B5%A6%E5%A4%A9%E4%B8%BB%E5%A0%82&exclude=&search_type=0&showDetailOn=true&option%5Bis_japanese%5D=&option%5Bshape%5D%5B%5D=

Francis Xavier led Christian missionaries to Japan in 1549, largely focusing on the southern island of Kyushu and nearby Yamaguchi. However, the religion was gradually repressed by the nation’s leaders, sometimes with loosely enforced bans, other times brutally—such as when Toyotomi Hideyoshi crucified six foreign missionaries and 20 Japanese converts in 1597. By 1650, the religion had been pushed entirely underground, with practitioners—dubbed Kakure Kirishitan (“Hidden Christians”)—concentrated in the islands west of Nagasaki.

After Commodore Perry forced Japan to open up its ports, O-ura Cathedral (大浦天主堂・O-ura Tenshu-do) was built for French nationals in Nagasaki as part of a subsequent commercial treaty in 1864. By this time, Christianity had become permissible for foreigners, but was still forbidden to Japanese nationals.

However, in 1865, a number of Kakure Kirishitan emerged to confess themselves openly at the new cathedral. Having secretly passed down their faith for more than two centuries, the event was referred to by Pope Pius IX as the ”Miracle of the Orient." When the ban on domestic Christianity was finally lifted in 1873, dozens of beautiful churches were built on the coasts and islands of Nagasaki and Kumamoto, many of which can still be visited today.

12. One Clan Held Off the British, Inspired Van Gogh & Overthrew the Shogun (1862-68)

The Satsuma Domain, now Kagoshima Prefecture, was among the most aggressive in adopting Western technology in the 19th century, and one of the first to successfully produce the reverberatory furnace necessary for iron cannon production.

When a British merchant, Charles Lennox Richardson, was killed by samurai from the Satsuma Domain for failing to give way to their daimyo’s father in 1862, the British responded by demanding restitution: 100,000 pounds from the Tokugawa government and 25,000 pounds from Satsuma. The Tokugawa paid; Satsuma refused.

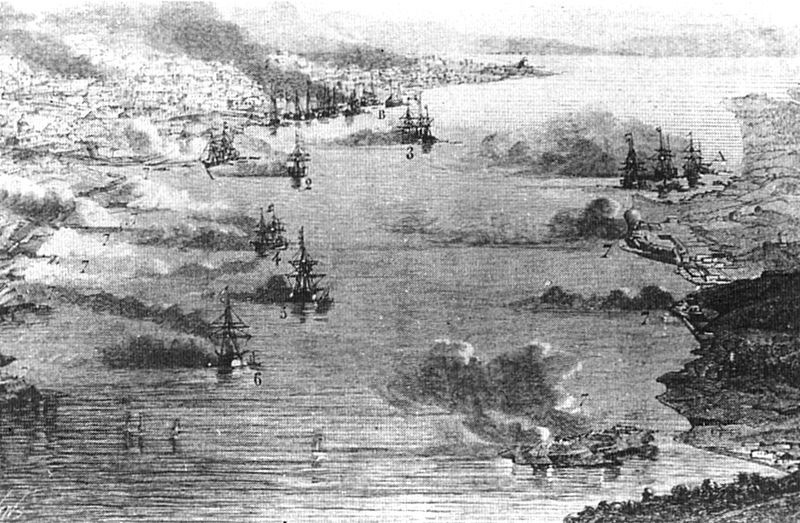

Seven British warships were deployed to Kagoshima Bay on August 11, 1863 and when negotiations failed, hostilities ensued. However, Satsuma had cannons of its own, and although much of the (evacuated) castle town was destroyed, the fleet’s captain and second-in-command were among those killed. Though not all sources agree, commonly cited figures suggest that 13 British and five from Satsuma lost their lives. And though Satsuma ended up paying the 25,000 pounds in reparations (borrowed from the shogunate, which it never repaid), Britain began to see Satsuma as a viable alternative to dealing with the Tokugawa in Edo, where France was gaining sway.

Two years later, in 1865, 19 young men from Satsuma defied the shogunate and secretly went to Britain to study Western technology. Upon their return, in addition to bringing back various industrial-age skills, the students arranged for Satsuma to present its own pavilion, separate from the shogunate’s, at the 1867 Paris World’s Fair—an event credited with inspiring Vincent van Gogh’s Japan-style art, and further reinforcing the Japonism movement that had already taken hold thanks to woodblock ukiyo-e prints brought back by Dutch traders.

In 1868, the Satsuma Clan, along with Choshu in what is now Yamaguchi Prefecture, led the forces of the Meiji Restoration to topple the Tokugawa shogunate, ending a system that had ruled Japan since 1603. Many of the Satsuma students would go on to become ministers and ambassadors under the Meiji government, as well as founding the institutions that would eventually become the University of Tokyo and Tokyo National Museum.

Bonus: One of the World’s Largest Tombs Was Built for a Japanese Emperor (399)

https://pixta.jp/tags/%E5%A4%A7%E4%BB%99%E9%99%B5%E5%8F%A4%E5%A2%B3?utf8=%E2%9C%93&keyword=%E5%A4%A7%E4%BB%99%E9%99%B5%E5%8F%A4%E5%A2%B3&search_type=0

The Kofun Period (third century-seventh century) was the fourth major period of human history in Japan, following the Paleolithic (30,000-14,000 B.C.), Jomon (14,000-300 B.C.) and Yayoi (300 B.C.-third century A.D.). During this time, colossal tomb-mounds called kofun were constructed for Japanese nobles, members of the imperial family and powerful members of the central government, thus giving the period its name.

The Nihon Shoki (日本書紀), Japan’s second-oldest book of classical history, records that Emperor Nintoku, traditionally considered Japan’s 16th emperor, died and was entombed in the year 399. His burial place is believed—with some uncertainty—to be the Daisen-ryo Kofun (大仙陵古墳), now found in Sakai City, Osaka. Shaped like a keyhole outlined by three moats when viewed from above, the tomb measures 486 meters (1,594 ft) in length and 35.8 meters (117 ft) in height, making it Japan’s largest keyhole-shaped tomb.

Nintoku’s Tomb further asserts to be the third-largest tomb in the world, after the Great Pyramid of Giza and China’s Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor—though how truly it supersedes lesser tombs depends on whether you measure height, volume or surface area, and where you start measuring. The Great Pyramid is a much larger 138 meters (451 ft) high; the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor is now just 47 meters (154 ft) high, but 515 meters (1,690 ft) long. But given that most people don't even know that Japan had a period of colossal tomb-mound construction, Nintoku's Tomb is worthy of a mention!

This style of burial was phased out as Buddhist precepts took hold in the mid-sixth century.