The Sendai Tanabata Star Festival

We're seeing stars at the Sendai Tanabata Star Festival! One of Japan's most popular summer festivals, you'll be in awe at the festivities held every year in Sendai.

By Kim Yanghyeon

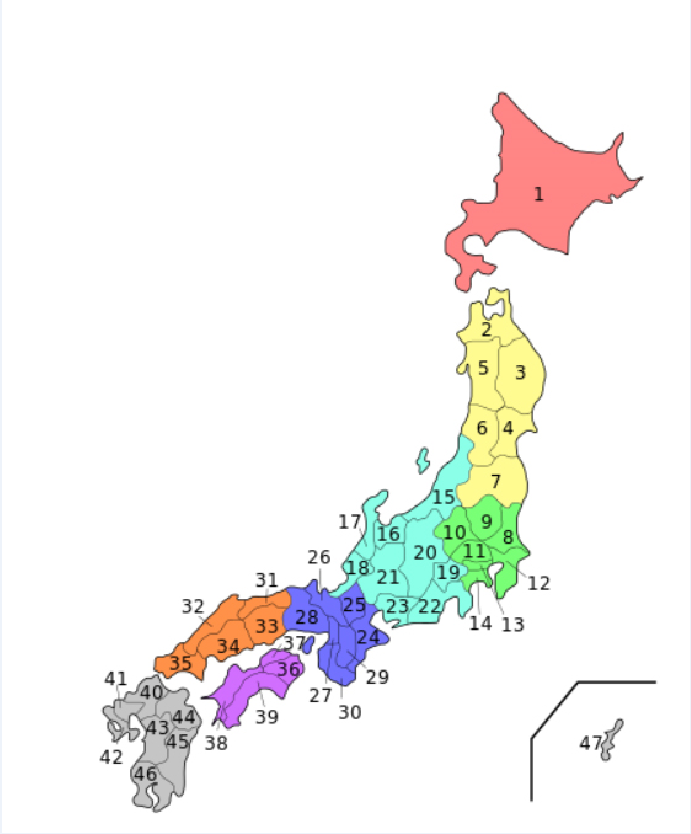

In the summer, regions across Japan host many religious festivals called matsuri. The yellow area is Tohoku, in northeastern Japan (numbers 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7), where summer matsuri are held in July and August.

Aomori's Nebuta Festival (2)

Akita's Kanto Festival (5)

Iwate's Sansa Odori Festival (3)

Yamagata's Hanagasa Festival (6)

Miyagi's Tanabata Festival (4)

Fukushima's Waraji Festival (7)

In 2017, I headed to Sendai to attend the final day (August 8) of one of these major events—Miyagi's Tanabata Festival.

Miyagi Prefecture is famous for being the home of Date Masamune, the lord of the Sendai Domain in Japan's feudal days. From that time forward, one of Tohoku's biggest festivals has been the Sendai Tanabata Star Festival. Date was a small child, never growing taller than 160 centimeters (5'2"), who lost sight in one eye due to a bout of smallpox when he was quite young. However, he dedicated himself to developing relationships inside and outside Japan, interacting with England and other countries in the 16th century. Sendai became known for many historical firsts due to the delegations that it sent abroad. The Tanabata Festival supported by Date has continued to this day, overcoming many challenging crises, such as earthquakes and bombardment during the war. Previously, I had only been able to see it on television, but now I had arrived at the actual site.

It's fortunate that the festival information counter inside Sendai Station offers maps in Korean.

On that particular day, a typhoon was lingering in Sendai. Luckily, however, most of the festival decorations are hung in a covered shopping arcade, so rain does not dampen the brilliant display.

I headed to the arcade a short distance from the station. I saw the first decorations swaying in the wind drifting in from the arcade entrance.

It seemed that this year's design involved shops putting up ornaments in front of their businesses while displaying their creative artwork for the year. I stopped in front of the most strikingly attractive decoration among the numerous ones present. Standing fixed in front of the display labeled "2017 Tanabata Gold Medal Recipient," I was surrounded by crowds snapping pictures. Curious. Why was this Tanabata Festival so popular when they did not have the kinetic energy, parades, and processions found in other regions? I found the answer in the artistry of this gold medal winner.

In the middle of a cluster of five decorations was one with Date Masamune, the one-eyed samurai who promoted this festival. More than any of the other works, this particular one drew the most attention and had been handmade using only traditional Japanese washi paper.

Where the arcade came to a T-intersection, more Tanabata decorations were fluttering in the breeze.

To my list of favorites, I added the red decoration put up by an airline company. I could tell that it was supposed to be a Japanese airplane just from the color pattern. At first, I had thought that Tanabata decorations were only made by people in the local area, but I guess companies make them as well.

As I walked some more, I saw quite a few decorations put up by each shop. The thousands—or even tens of thousands—of decorations had slight variations. I started to wonder who made these designs every year and how they made them.

My eyes caught a panda decoration, no doubt reflecting the happy mood that had run through society when news broke that a baby panda had been born at Ueno Zoo this year.

Popular characters were also portrayed in the decorations.

As I took a look at these sights throughout the arcade, the number of questions I wanted to ask kept growing. Along the walkway, I met staff members and volunteers working on the festival. The staff members wore yellow T-shirts and were able to provide explanations of the Tanabata Festival. The people in blue T-shirts were volunteers who were there to help tourists take pictures during their visit.

If I had been a visitor unable to speak Japanese, the volunteers could use a translation device to help them approach anyone they heard asking someone to take their picture or anyone they saw using a selfie stick or standing with their family and trying to take a picture. The happy smiles of the two volunteers I met were very contagious. There were more people wearing volunteer T-shirts than I had expected. One of them gave me a recommendation for a very tasty place to eat. I was able to learn all kinds of things about the festival and it made the experience even more enjoyable for me.

Tanabata, with huge decorations beautifully coloring the arcade. Was it just me, or were these small, decorated bamboo branches in one corner of the mall the same decorations you could find outside Sendai during other July 7 Tanabata Festivals? I talked to a staff member in a yellow T-shirt and she said that although it had been canceled due to the typhoon, there is usually a hands-on workshop where participants get to make the seven most popular types of Tanabata decorations.

I mentioned that if some of the materials were still available, I would like to take part in the canceled workshop. I was in luck because they told me they would take me to someone named Ms. Yamamura, who makes the Tanabata decorations.

Inside her room was beautiful washi paper and many of the decorations I had seen hanging outside.

As I waited for Ms. Yamamura, I looked at the designs. Being the final day of the festival, it seemed like things were really busy. This was the decoration-making kit.

Finally...

While listening to her instructions, I carefully folded the traditional washi paper into a small kimono. I love this kind of delicate task. It was a lot of fun to take a simple square piece of paper and turn it into a beautiful kimono.

Ta-dah!

After folding a red obi sash, it was complete. It was my first try at this and folding washi paper is not very easy. I made the left side of the sash too big, darn it.

But I managed to make seven decorations to hang from the bamboo. Then I wrote my wishes down on a tanzaku streamer to hang beside them.