A Primer on Japanese Homoerotic Manga

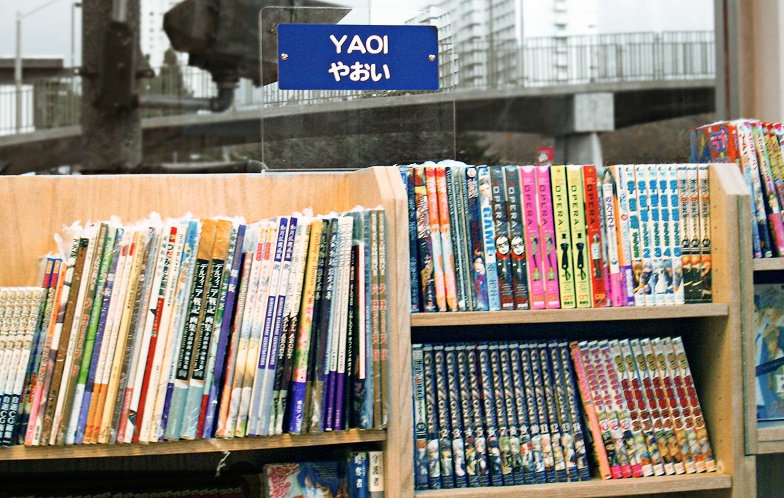

If you step into a major comics shop like Animate in Ikebukuro, you'll soon stumble upon piles of seemingly LGBT-themed manga, with covers more or less explicitly alluding to a romance between boys. But are those volumes really created for a homosexual male audience? Actually, the answer might surprise you!

By Diletta FabianiYaoi & BL: Gay for Girls?

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Yaoi_Books_by_miyagawa.jpg

When talking about Japanese manga depicting homosexual relationships, the first thing to do is to differentiate the intended audience. In fact, most manga in Japan that's centered around homosexual relationships is actually created for a heterosexual female readership.

Let’s first look at manga featuring male characters in varying homosexual configurations. The best-known categories of yaoi (as it’s mostly known in the west) or "Boy’s Love" (shortened to BL) are generally not created with the LGBT community in mind, but rather to fulfill the fantasies of heterosexual girls and women.

Why Make This Distinction?

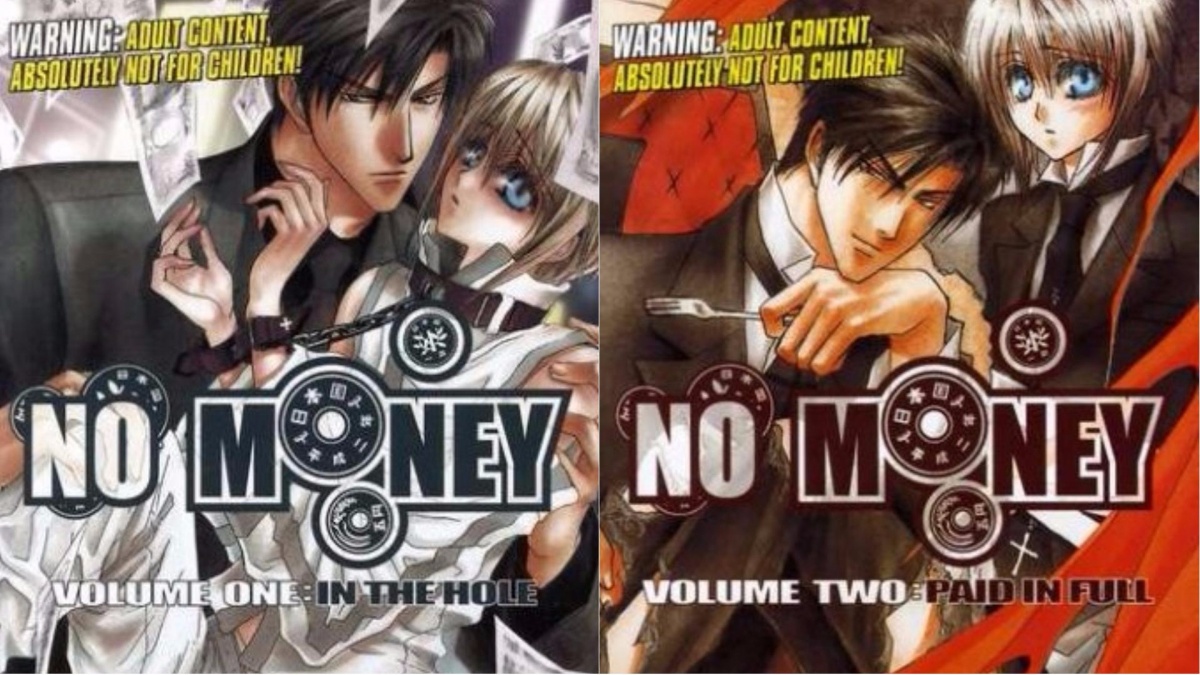

https://www.amazon.com/No-Money-Volume-1/dp/B000X20SLQ/

One might find that this genre of manga often includes a very stereotypical character division, with a seme (the “dominant” character, often physically fit with a more extroverted and/or aggressive personality) and a uke (the “passive” character, physically less hunky and often younger). These two are usually in a very hierarchical relationship, where one clearly dominates the other... in every sense.

The seme tends to embody the stereotype of masculine manga characters not only in appearance but also psychologically: a restrained yet confident macho male pursuing the soft-spoken and gentle (or, in a variation of the character, loud and feisty) uke. Both characters follow the imagery of bishonen—a term describing a specific set of aesthetics that includes slender bodies, clear skin, stylish hair and androgynous facial features. The picture above, a cover from the manga No Money (Okane ga Nai, お金がないっ), perfectly exemplifies these stereotypes.

https://www.amazon.com/Under-Grand-Hotel-vol-2-Sadahiro/dp/193412947X

The manga in this genre range from slice-of-life stories to fantasy, from high school romances to weirder settings—like mafia empires or prisons—and include various levels of explicit content depending on the authors. Pictured above, Under Grand Hotel is a good example of an explicit BL manga set in a prison. BL manga has its own relatively rich section in manga stores as well as magazines dedicated to the genre.

In conclusion, while several authors have started breaking stereotypes and offer more realistic relationship dynamics in BL manga, the aesthetics of males with fine features and slender bodies and certain tropes of the genre, like the seme/uke division, are still prevalent.

Yaoi & BL in Western & Japanese Vocabulary

https://pixabay.com/photo-1487275/

Various terms have been used in the past for BL, and there seems to be a division among how the terminology evolved in Japan and in the West. The term yaoi in particular sees two different usages.

The term itself was created in the late 70s by Yasuko Sakata and Akiko Hatsu, and it's an acronym for the words “Yama nashi, ochi nashi, imi nashi" meaning "No climax, no denouement, no meaning." This phrase was used to indicate how yaoi skipped directly to the "interesting" part of the story, while earlier shonen-ai manga had more complicated plots (shonen-ai referred to stories featuring platonic relationship between boys).

Nowadays, the term yaoi sees two different usages in Japan and in the West. In Japan, it mostly indicates parody dojinshi (a term indicating self-published work, often inspired by popular series by other authors) of popular characters and/or manga focusing on sex scenes with little plot. While in the West, it’s often used as a general term for all products—not only manga, but also anime, video games, etc.—featuring homoerotic material targeting a female clientele.

How did this division come to be? With the spread of the internet, fan-made translation and scans of BL manga started to circulate among Western fans and a found a dedicated fandom. Nowadays, popular BL manga is published and translated in countries outside Japan, albeit covering a small niche in the manga market. During this expansion to the West, the vocabulary seems to have started diverging.

The 'Rotten Woman' Fandom of BL

https://www.amazon.co.jp/%E8%85%90%E5%A5%B3%E5%AD%90%E5%BD%BC%E5%A5%B3-DVD-%E5%A4%A7%E6%9D%B1%E4%BF%8A%E4%BB%8B/dp/B002EO5W2G/ref=sr_1_2?s=dvd&ie=UTF8&qid=1492873925&sr=1-2&keywords=%E8%85%90%E5%A5%B3%E5%AD%90

The fact that this genre targets females can be also be ascertained by the ubiquitous fujoshi figure in popular culture. A fujoshi (腐女子) is a female fan of BL, and the term literally means "rotten woman" (a kanji pun where the first character in the word fujoshi, 婦女子, an existing term indicating women, is changed with an homophonic equivalent 腐, meaning “to rot”). At first, it was used by the media but then reclaimed by fans themselves, and it indicates fans of BL who often also like to imagine homosexual relationships between male characters in heterosexual works of art. The fujoshi figure is so well-known that it has often been used in drama and even manga, sometimes blurring into a more general figure of female otaku. The picture above features a movie adaptation of the popular light novel series Fujoshi Kanojo, which follows the story of a boy who falls in love with a fujoshi. While the male equivalent—called fudanshi or fukei—exists, it's a minority within the minority.

Yuri or GL? Girls Steal the Stage

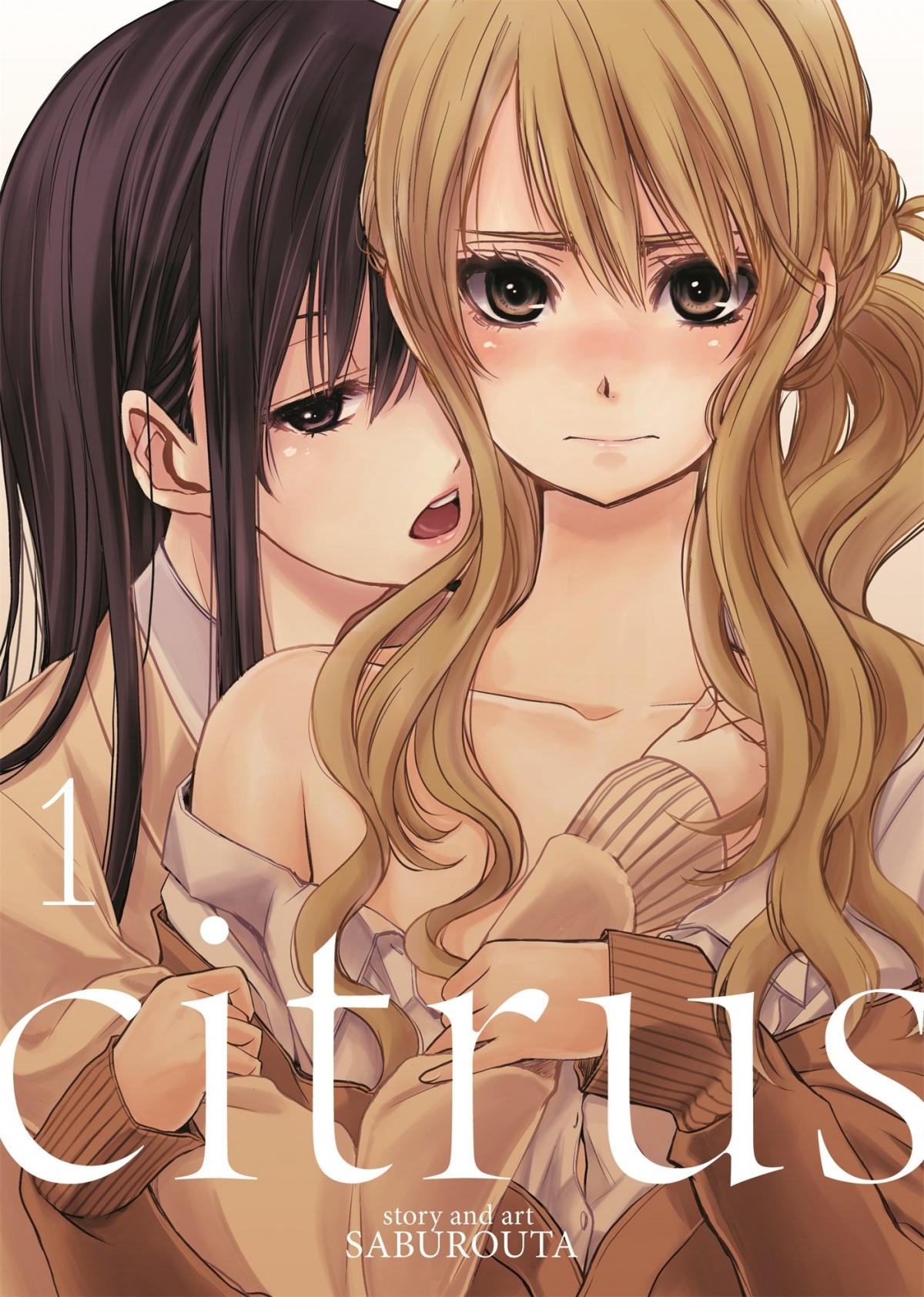

https://www.amazon.com/Citrus-Vol-1-English-Version/dp/1626921407/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1492874196&sr=8-1&keywords=citrus+manga

So we concluded that Boy’s Love is not actually written for boys, but mostly for girls. What about the lesbian equivalent? Yuri (also called GL, or Girl's Love), the girl-on-girl equivalent of BL, also originated from female-oriented magazines, even though it also appears now in male-oriented ones. In the West, the term has been used—like the yaoi counterpart—to indicate the more explicit content, with shoujo-ai indicating more romantic stories.

Yuri comics started to appear on the market in the 70s, reaching a certain popularity and more acceptance only in the 90s, with a yuri-only magazine finally being published in the early 2000s. Initially, most stories would see a love between an older, sophisticated woman and a younger girl, and such love would more often than not become impossible due to societal pressure and end in tragedy with the death of one or both lovers. However, in the 90s, manga artists started to move away from such stereotypes, realizing stories with happier endings and characters of the same age, like Citrus, a popular yuri created in 2012.

https://pixabay.com/photo-1733995/

The line among heterosexual and lesbian audiences is, however, more blurred in the case of yuri. Some argue that the while yuri manga is mostly read by females rather than males (or at least in equal parts), more explicit girl-on-girl anime is the place to find male heterosexual consumers—as opposed to BL, which performs better in manga form in terms of sales. This might be related to the fact that while manga is a socially accepted hobby at all ages (as indicated by the seinen market, addressing more serious and “adult” themes), anime is generally seen as something that mostly teenagers or a young male audience would prefer.

Additionally, well-known shojo series like Sailor Moon or Revolutionary Girl Utena that hint at, or openly portray, homosexual female relationships, are quite popular with female audiences.