A Fulbright Fellow's First Time in Japan

Ari Beser is an American writer, photographer and Fulbright fellow. All About Japan sat down to talk with him about his first time coming to Japan and the very personal story that brought him to Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Fukushima.

By Wendell T. HarrisonWhy did you decide to come to Japan?

Traveling to Japan was a childhood dream. The land of anime, flashing lights, high technology, and talking toilet seats had always been on my radar, but it wasn't until I was actually on the plane did I remember where my curiosity came from.

When I was eight years old, I met an atomic bomb survivor from Hiroshima and her niece, family friends of my mother's who were visiting from Japan. This woman—who shall remain nameless due to the generational discrimination faced by atomic bomb survivors, or hibakusha—used to work with my grandfather when she lived in America in the '60s and '70s.

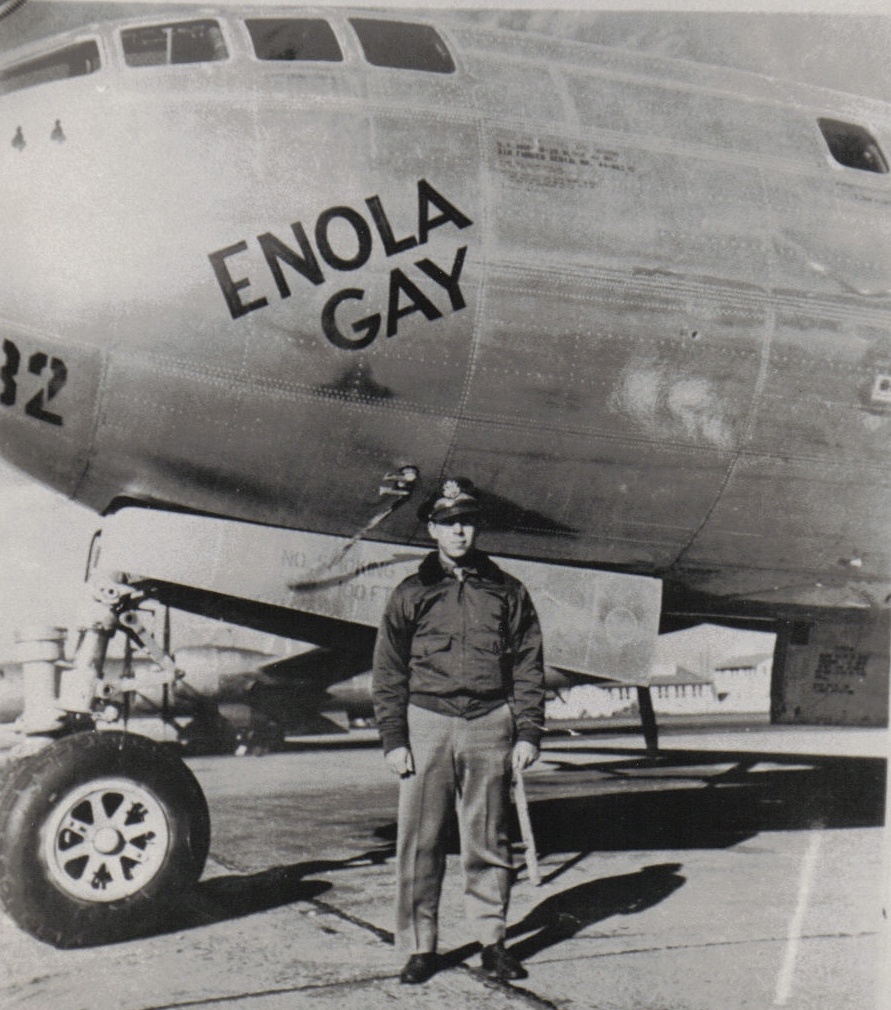

When I met her, I couldn't help but be amazed. “Mom,” my eight-year-old self asked, “Don't you think it’s strange that you and grandpa are friends with a survivor, and Pop Pop was on the airplanes that dropped the bomb?”

Airplanes? Plural?

Yes. "Pop Pop" was my grandfather Jacob Beser, the only man in the world to fly on both planes that dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Years later, on March 10, 2011, I received word that I'd won a grant to travel to Japan and write a book about my Pop Pop and the woman who survived in Hiroshima. That night was already March 11 in Japan. The 9.0 magnitude Great East Japan Earthquake struck the Tohoku region, triggering a tsunami that washed away the lives of hundreds of thousands of people.

Due to the disaster at Fukushima, many people encouraged me to cancel my travel plans. I refused. I knew I had to follow this path. To finish my book, I had no idea how far the path would go or where I would end up, but I knew I had to try.

When I arrived in Kansai where the Japanese woman’s family lived, I asked them if they would work with me to send this message of peace. “No,” they said flat out. “We will be your friends, but you must meet as many living hibakusha as you can before it's too late. They are old now, they are dying and they have a message. If you meet them, they will help you understand what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Since then I have worked to meet as many hibakusha as I could.

How were you able to meet them?

http://www.aribeser.com/contact/

I contacted the Hiroshima Peace Museum and they introduced me to two English-speaking survivors, one of whom, Keijiro Matsushima, has since passed away.

Asahi Shimbun introduced me to the artist Shinpei Takeda, who taught me that there is no such thing as truth when it comes to war: Everyone has their own truth to which they cling, and only when you comprehend the other side do you realize that we are all just humans who suffered tragedies.

Shinpei introduced me to the family of Sadako Sasaki, the girl who folded 1,000 paper cranes. When I met Yuji, Sadako’s nephew, he put Sadako’s last paper crane in my hand, and asked me if I would work with him and the grandson of President Truman to come together for the sake of peace.

The following year we were back in Japan and—thanks to the graciousness of an NPO called the Asian Network of Trust: Hiroshima (ANT), and supporters in Nagasaki—we were introduced to every single survivor that has appeared in my book, each of whom asked us to send their message to the world.

How well do you think you've kept your promise?

http://www.aribeser.com/blog/

The first thing I did in Japan was to meet them, the hibakusha, to listen to their stories and send them to the world. Now I am back with National Geographic as a Fulbright fellow, not only sharing hibakusha stories, but also sharing the humanitarian consequences of both military and civilian nuclear technologies with the experiences of Fukushima’s nuclear refugees as well.

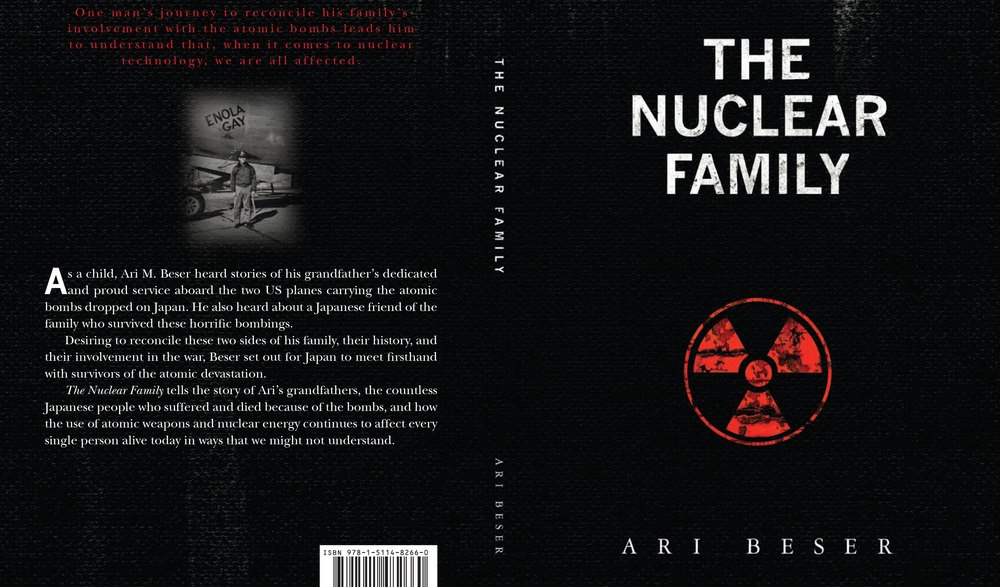

Oh, and I finished my book, too. I called it The Nuclear Family.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6yR5OUVb2gY

You can read more about Ari's incredible adventures in Japan at his website below, and be sure to catch his 2015 TEDx Kyoto video above.