Teaching at a Japanese University

Landing a teaching job in Japan isn't particularly difficult. In most cases, you'll get hired without ever stepping foot into the country, provided you have a bachelor's degree, proven English competency, and don't completely blow the interview. However, those seeking a job at a university have a few more hurdles to jump.

By Wendell T. Harrison1. The Easier Way

http://www.westgate.co.jp/application/

The easier way to get a campus gig is through a recruiting agency, or a company that dispatches teachers to universities. There are several agencies out there, and some eikaiwa (English conversation) schools offer this service as well. However, while they have roughly the same hiring requirements, these agencies typically pay a little more than the standard English conversation school. The pay from these jobs could be monthly or hourly, depending on your particular contract.

One well-known and competitive company is Westgate, an agency that hires teachers for monthly pay that starts at ¥260,000 (US$2,389) for less-experienced teachers and comes with a round-trip ticket for successful applicants living abroad.

2. The Harder Way

http://www.fla.sophia.ac.jp/meetprofessors

Getting hired directly by a Japanese university is a more daunting form of job hunting, and universities require a lot more on their applicants' résumés. Far beyond the expectations for an eikaiwa position, universities typically insist the instructors have a master's degree in TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language) or a related field, prior teaching experience (preferably in Japan), and published articles in field-related academic journals. While conversational Japanese ability and holding a PhD are not always requirements, these qualifications will surely set you apart from the rest of the intrepid instructors-to-be.

3. Pay Structure

http://game-designschools.com/game-designer-salary-expectations/

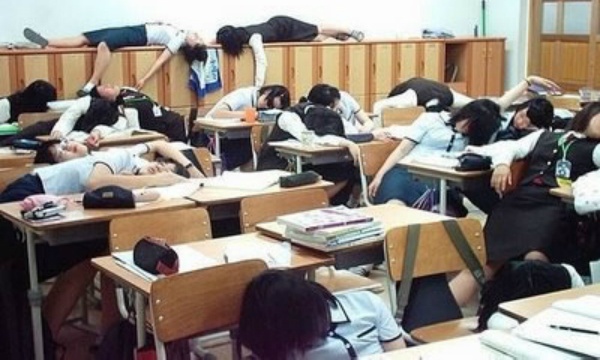

University lessons are generally arranged in 90-minute blocks called koma. And if you pass by some classes, you may see a few students sleeping peacefully through the lesson very much as if in a—ahem—coma.

Part-time professors are paid per koma, and even better, they are typically paid through the summer even though they won't be teaching. Of course, the wages vary by school, but a typical estimate for each koma is around ¥20,000 to ¥40,000 (US$184-$368).

Full-time professors, on the other hand, are paid a monthly salary, and are often given a day off teaching every week to conduct research or for writing. Since full-time professors are expected to represent the school through scholastic publications, that day off is anything but a holiday. The salary range typically scales around a much more pleasing ¥300,000 to ¥600,000 a month (US$2,756-$5,513).

4. Student Life

http://singersworld.wikispaces.com/classrules

While each university is different, the general truism in Japan is that the hardest part of university is getting in. Having worked themselves into the ground through six years of junior high and high school just to get into a good university, once they're accepted, many students will simply coast until graduation. They'll attend classes, but they won't necessarily be attentive.

In some schools, the faculty have all but given up on trying to rouse their students from their slumber or getting them to stop sending text messages in the middle of class. There's an upside, though: the students who are awake are often very focused and dedicated to learning, which makes the job more worthwhile.

Students aren't all sedentary, of course, and some take full advantage of campus life. School activity groups, called circles, are very popular, and the students take a lot of pride in their extracurricular activities and school events. It's often considered a big deal to see non-Japanese teachers in attendance at certain circle events, so it can be nice to use your local celebrity to help the students feel their extracurricular efforts are being validated.

5. Turnover & Uncertainty

Every rose has its thorn, and for teaching at a university, the major issue the high rate of turnover and uncertainty of contract renewal. The vast majority of foreign university teachers in Japan work on renewable, fixed-term temporary contracts. Unless you become a tenured instructor, akin to obtaining the Holy Grail of teaching positions, each year you'll be on pins and needles waiting to see if your contract will be renewed.

The scary part is, this may have nothing to do with teacher performance. Perhaps one department ran out of funding and had to release a few instructors. Or maybe you've lived in Japan too long to be considered capable of having a first-hand understanding of the current state of the world outside Japan. Or, more likely, the university has a cap on the number of consecutive years it will hire staff to avoid having to convert them to permanent positions (legally five years for most jobs, but 10 years for universities). The factors can be quite arbitrary, and teachers can be left in limbo while waiting to get their next contract confirmed.

In fact, it's important to understand this factor before even applying, because university-level teachers need to quickly learn how to ride this process and start building a network of resources and references for the next job. This network, along with exemplary research and a proven record of academic success, is the key to having a university invite you to stay for the long haul—or at least for another year.