Better Know Your Shochu

There are several reasons to drink shochu (焼酎). Not only is it one of the most typical Japanese drinks, its distilling method makes it less caloric than other similar beverages, and its purity leads to less hangover effects. So, are you ready to become a true shochu expert?

By Diletta FabianiA Bit of History

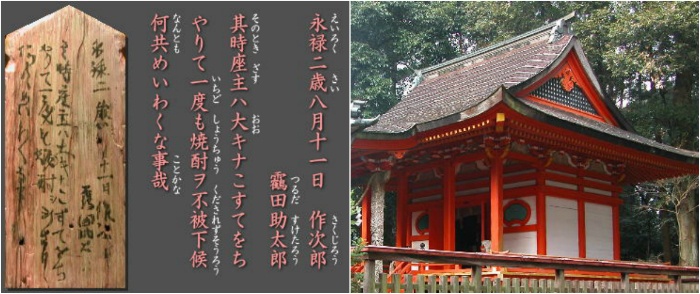

Kyushu, and more specifically Kagoshima, has long been associated with the origin of shochu. The first known appearance of the word is some 1559 graffiti written by construction workers on the roof of the Koriyama Hachiman Shrine that says, "The high priest was so stingy he never once gave us shochu to drink. What a nuisance!"

It’s hard to tell where specifically the distilling technique comes from, but it seems that it originated in Persia and then spread east toward India, Thailand, Okinawa and finally the south-west region of Japan.

Otsurui vs. Korui

There are two main types of shochu: otsurui (乙類) and korui (甲類). Otsurui shochu is distilled only once and often consumed by itself, given the stronger smell and flavor. Korui shochu, on the other hand, is distilled multiple times, making it nearly tasteless and perfect for cocktails.

Otsurui shochu is also called honkaku shochu (本格焼酎 ), or "authentic shochu," since the single distillation is the original method used to produce the beverage. Mass production only started when machinery for repeated distillation was imported from Great Britain in the Meiji Period (1868-1912).

Otsurui shochu and korui shochu can be blended to make konwa shochu, which tries to combine the price benefits of mass production with the distinctive taste of the purer shochu.

How Is Shochu Made?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n2GNaeIwVuc

Shochu typically starts with rice or barley, which is steeped in water, steamed and cooled. Mold spores called koji-kin (a kind of Aspergillus fungus) are sprinkled over the raw materials to transform their starches into sugar over a period of roughly two days, a process known as saccharification. The result is simply called koji, which is added to water and yeast, which breaks down the glucose into unrefined alcohol over about a week. This results in what's called moto (literally, "foundation" or "origin"), or first-stage moromi (fermentation mash).

The main ingredient, such as rice, barley or sweet potatoes (as in the video above), is then added to the first-stage moromi along with more water, creating second-stage moromi. After roughly eight to 10 days of secondary fermentation, the second-stage moromi is transferred into stills for distillation to obtain the final product.

While shochu is generally classified based on its main ingredient, there are also different kinds of koji that create different kinds of moromi with different flavors. White koji is the most common. It's easy to cultivate, grows rapidly, and creates a drink with a gentle taste. On the other hand, black koji is mostly used in awamori, a variety of shochu from Okinawa. Finally, yellow koji, which is used to produce sake, was once used for shochu as well, but its temperature sensitivity makes it difficult to work with in the warmer regions where shochu is most popular. It results in a rich, fruity flavor.

Varieties of Shochu

http://blog.umamimart.com/2013/11/umami-map-where-to-buy-shochu-in-the-bay-area/

While Japanese laws admit a countless number of varieties of shochu the following are among the most famous.

Kome-jochu (米焼酎)

Kome-jochu shares its main ingredient, rice, with sake (except in sake the rice is brewed, not distilled). Kome shochu has a thick, mild taste that goes well with Japanese specialties like sashimi, tofu or rice-based dishes. Kumamoto Prefecture is well-known for kome shochu, especially Kuma Shochu, produced in Hitoyoshi-bonchi, a fertile basin in the southern part of the prefecture.

Imo-jochu (芋焼酎)

This potato shochu was originally produced in Kagoshima and Miyazaki Prefectures, with Kagoshima's Satsuma Shochu brand being geographically protected. It has a sweet, stronger taste that might not meet everyone’s liking, but it goes well with fatty dishes, cheese and fried foods.

Mugi-jochu (麦焼酎)

This shochu is made from barley. With a milder and cleaner taste compared to the previous two varieties, it's easier to drink and perfect to accompany simpler dishes like fish. Produced mostly in Oita Prefecture, Miyazaki Prefecture and Nagasaki Prefecture, Nagasaki’s Iki Shochu has also been given geographical protection.

Soba-jochu (そば焼酎)

As the name suggests, this shochu is made from soba, or buckwheat. It was invented in 1973 by the Unkai Brewery of Gokase Town in Miyazaki Prefecture. Now it’s produced all across Japan, known for tasting milder than mugi shochu and vaguely bitter, making it a good accompaniment to spicy meat and fried seafood.

Kokuto Shochu (黒糖焼酎)

Hailing from the Amami Islands in Kagoshima Prefecture, this brown sugar shochu has a history dating back to the Edo Period (1603-1868). It’s not very common further away from the islands, but its subtle sweetness couples well with condiments like soy sauce and dishes like yakitori (grilled chicken).

Awamori (泡盛)

Okinawan shochu is made from a special type of rice, called long-grain Thai Indica rice, and is fermented with the indigenous black koji mold. Traditionally aged in clay pots to improve its flavor, it has a strong scent and mellow taste, perfect to accompany heavy or creamy dishes. While it generally contains about 25 percent alcohol, this shochu variant can go up to 43 percent in some cases. For example, a variety called hanazake (花酒), manufactured on Yonaguni Island and originally used in religious ceremonies, has a 60 percent alcohol content. Ryukyu awamori has also been designated a protected geographical indication protected by the WTO's TRIPS Agreement on intellectual property.