Seeker of Japanese Spooks: Lafcadio Hearn’s Life in Matsue

Koizumi Yakumo (Lafcadio Hearn) and his wife, Setsu. (Photo courtesy of Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum)

The Greco-Irish writer became Japan’s master of macabre storytelling—and the city of Matsue is the perfect place for a close encounter.

By Matt Alt

I am in a “ghost tour,” standing in the gloaming darkness on the grounds of Matsue castle when a great crack of thunder peals above. A silence falls over our small group, which is listening to story about a legend within the castle walls that stretch before us. “Long, long ago, a maiden of Matsue was interred beneath them – alive,” the storyteller had only just begun, before being interrupted by the blast from the heavens. We all giggle nervously. Is this some kind of sign? Our guide clears her throat and starts again. “The unfortunate girl’s name was never recorded, but her sacrifice…” Another interruption! This time, a meowing from the darkness. Suddenly a stray cat rushes out of the shrubbery to the storyteller, walking figure-eights around her legs. There’s no question about it, we all agree. The maiden is here! This is enough to give even the most jaded a chill down their spine. It’s a quintessentially Matsue moment, based on a quintessentially Lafcadio Hearn story.

“No one ever goes to Matsue,” wrote a reporter for The New York Times in 1974. Just “occasional tourists – and Lafcadio Hearn.” Times have changed. People most certainly do go to Matsue – and often because of Hearn, its most famous foreign resident.

" He wrote for newspapers there, then moved to New Orleans, where he immersed himself in the city’s culture, chronicling everything from crime to cuisine to Voodoo.”

Hearn, who lived from 1850 to 1904, was a journalist by trade. But his true calling was as a teller of tales of terror. Born in Greece, he was abandoned by his father and mother, then sent by an aunt to be raised by distant relatives in Ireland, France, and London. When Hearn turned 19, he was put on a ship to the United States. He wound up in Cincinnati, “dropped,” as he later wrote, “moneyless on the pavement of an American city to begin life.” He wrote for newspapers there, then moved to New Orleans, where he immersed himself in the city’s culture, chronicling everything from crime to cuisine to Voodoo. His keen eye for people and stories ignored by mainstream society caught the eye of a major national magazine, Harper’s. It sent him to report on the West Indies, and then, in April, 1890, Japan.

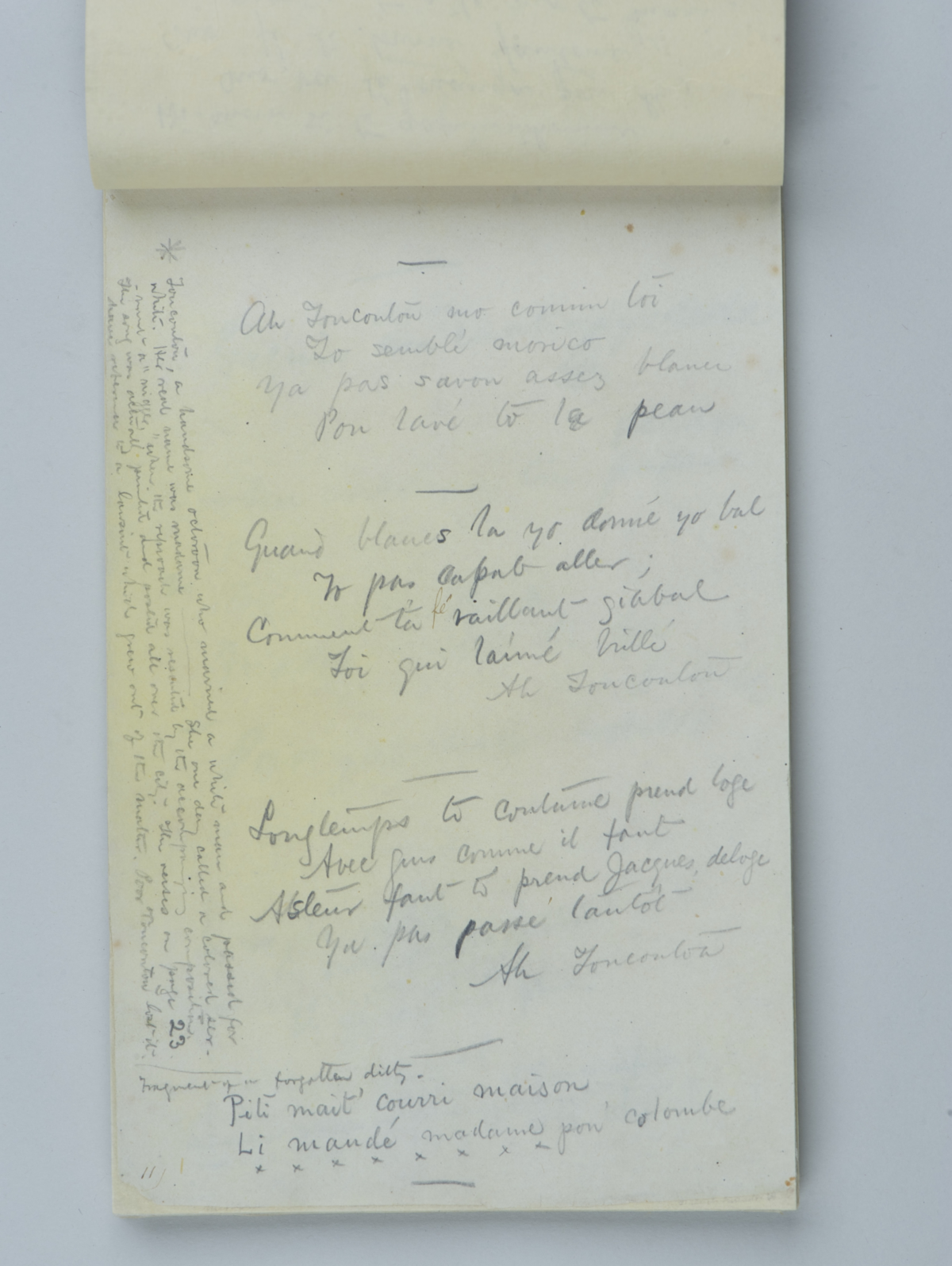

Hearn’s Field Notes from His New Orleans Days. (Photo courtesy of Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum)

Today, this sounds like a refreshing sort of assignment. Japan is renowned as a factory of fantasies. Its playthings can be found in homes around the planet; its games in pockets all over the world; its manga occupy bestseller lists worldwide; its anime competes head to head with Hollywood in movie theaters around the globe. Every year, millions of tourists flock to Japan to make contact with their favorite characters and stories. But this wasn’t always the case. For many years after the country opened its ports to the West in the mid-19th century, Hearn’s heyday included, the nation was widely seen as a hopelessly distant backwater, a supplier of charming arts and handicrafts but nowhere one would ever actually visit.

In Japan, Hearn became something more than a journalist. The nation’s culture, so different from his own, seduced and transformed him. For someone with a background as unmoored as Hearn’s, the chance to immerse himself in something totally new seems to have possessed keen appeal. Hearn threw himself into Japan like a man possessed, absorbing its customs like a sponge. Then he used his talents to share what he saw and heard with outsiders. Hearn wasn’t the first to transcribe Japanese stories for foreign readers, but he was among the first to deliver them without condescension or judgement, and the only one to do so with such literary panache that they took off among mainstream audiences. He unwittingly repackaged local folklore into a new commodity that paved the way for an international entertainment empire to come.

“. . . a portrait of a Japan less exotic than enchanted, a mysterious realm inhabited by as many ghosts and goblins as living people.”

In books such as In Ghostly Japan (1899) and Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1904), Hearn recounted tales of the weird he heard from Japanese story-tellers and citizens. Through this web of strange stories emerged a portrait of a Japan less exotic than enchanted, a mysterious realm inhabited by as many ghosts and goblins as living people. Decades later in 1964, the director Masaki Kobayashi took Kwaidan from page to screen in a film by the same name. It won the Jury Prize at Cannes, earned an Academy Award nod, and did a great deal to promote Japan’s growing reputation as a storytelling powerhouse.

First Edition of “Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things,” tales Hearn collected from story tellers and others. (Photo courtesy of Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum)

I think about all of this as I sit upon the tatami mats of a beautifully preserved traditional home in downtown Matsue. Built in the 1860s, it lies a stone’s throw from the spooky walls of the castle. Hearn once described those ramparts as “fantastically grim… a vast and sinister shape, all iron-gray, rising against the sky from a cyclopean foundation of stone.” He must have meant this as a superlative, for he chose to live here, just a few moments’ walk away. Lafcadio Hearn’s Former Residence, as the place is known today, sits next to the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum. Combined with Matsue castle and ramparts, it’s a great way to spend a day.

The Former Residence of Lafcadio Hearn. Photo courtesy of Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum

Inside, the house is anything but grim. Traditional Japanese homes can often feel dark and stuffy, but not this one. Sliding doors of antique glass make up the wall in front of me. Through them can be seen an immaculately curated Japanese garden, knotted trees of ancient vintage surrounding a raked-gravel “pond,” flanked by stone lanterns laden with decades of moss. The windows and greenery bathe the interior in warm light. How often had he sat here, working over the details of some story or another? I recall having seen Hearn’s favorite old-fashioned glass in a showcase in the museum next door, and am seized by a sudden urge to liberate it for a contemplative drink.

Adjacent to Hearn's former residence, the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum displays his treasured possessions, including autographed manuscripts and first editions. (Photo courtesy of Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum)

After a series of blow-ups with his American editors, Hearn abandoned journalism to teach and write. The great British Japanologist Basil Hall Chamberlain introduced him to a middle-school in Matsue, where Hearn taught English for fifteen months, starting in the summer of 1890. In Matsue he met Koizumi Setsuko, the woman who would become his wife, and from whom he took his Japanese name of Koizumi Yakumo. The pair married and settled in this house in 1891. It is here where they started a family, and where Hearn began writing a book that came to be called Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan. Now, 135 years later, I find myself sitting where they once sat, looking out at the same sights they had seen.

And the things they had heard.

“Hearn liked the shadows, peering into the places most people didn’t, whether Japanese or not, to find the true nature of things.”

“On quiet nights, after lowering the wick of the lamp, I would begin to tell ghost stories, ” wrote Setsuko in her memoirs, “Hearn would ask questions with bated breath, and would listen with a terrified air. I naturally emphasized the exciting parts of the stories, when I saw him so moved. At times our house seemed as if it were haunted.” She also confessed that after these sessions, “I often had horrid dreams and nightmares.” The things we do for love!

Hearn lost an eye as a child, and his remaining one was so myopic that he had to work with his face hovering just inches from the paper upon which he wrote. He had a special desk constructed to aid him, its surface much higher than standard, so that he didn’t have to lean over while he worked. An exact replica sits in the corner behind me. Of course, I can’t resist trying it out.

Sitting in this unconventional arrangement, with desktop nearly at chin level, makes me feel a little like a child in a high-chair. But the stories that Hearn spun from this perch were anything but childish. Glimpses used Matsue and its residents as a lens into the Japanese worldview. Its pages brim with evocative descriptions of Shinto and Buddhist ritual, and immersive depictions of local life and lore. He couldn’t have done it without Setsuko, who played a combination of cultural consultant, fixer, and interpreter for his explorations, all the while raising their children. And reading the occasional ghost story.

When Hearn was sixteen years old, he lost the sight in his left eye as the result of an accident. To bring his eyes as close to his paper as possible, he instructed his carpenter to build a desk much higher than usual. (Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum)

The peripatetic Hearn soon moved his family, first to Kumamoto, and then to Tokyo. But his experiences here seem to have left a deep mark on him. The San’in region, which encompasses Shimane prefecture (of which Matsue is the capital) and the neighboring Tottori prefecture, takes its name from mountains (san) and shadows (in.) In a literal sense, the name refers to the region’s sheltered location alongside the northern face of the mountains separating it from Okayama, Hiroshima, and Yamaguchi. “But Hearn liked such isolated places,” wrote Setsuko. “He liked Matsue much better than Tokyo.” Which is another way of saying, I think, that Hearn liked the shadows, peering into the places most people didn’t, whether Japanese or not, to find the true nature of things.

I wonder what he would have thought about Japan now, risen from the shadows to become one of the planet’s most popular destinations. I wonder what he would have thought about his role in all of that. He passed away of a heart ailment in 1904 at the too-young age of 54. But the spooks and monsters he introduced to the outside world now play a prominent role in the global imagination, from the folkoric yokai and yurei of his books to more modern ones like Godzilla, the Pokémon, and the baddies of anime hits such as Demon Slayer, Jujutsu Kaisen, and Chainsaw Man. If you find yourself dazzled by the limelight these pop fantasies are bathing in, you might consider a trip to the comforting shadows of Matsue, where Hearn laid the groundwork for it to happen. I like to think he’s still there, somewhere, watching all of us enjoy Japan just like he did, over a century before it was fashionable.