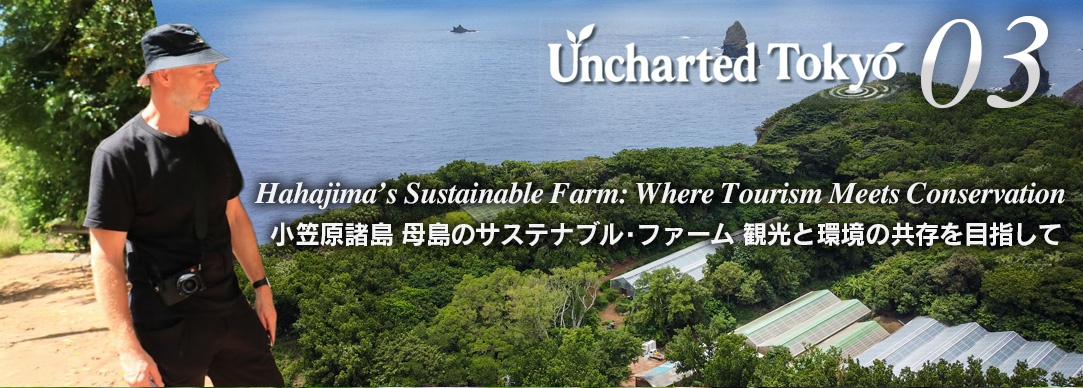

Uncharted Tokyo 3|Hahajima’s Sustainable Farm: Where Tourism Meets Conservation

When people think of Tokyo, they often picture neon-lit streets and busy crowds. But just beyond the city lies another side of Tokyo—one of islands, forests, and quiet mountain villages. In these lesser-known areas, you’ll find experiences that go beyond sightseeing: nature, culture, and community. Responsible travel here means slowing down, exploring with care, and discovering something new. Uncharted Tokyo—step into the unknown.

By AAJ Editorial TeamA Remote Farm with a Twist

It was hard to believe I was still in Tokyo. Yet here I was, eating one of the best mangos I’d ever tasted, on a tiny farm on one of the metropolis’s most remote islands. As the mango’s juice dripped off my chin and made a sticky puddle on the ground, I looked at the greenhouses nearby, full of tropical fruit and cacao, framed by the towering palms trees of the jungle around us—and felt about as far as possible from the crowded, hyper-modern city that is Japan’s capital.

Taekoni Farm, the eco-tourism project I was visiting, is located on Hahajima (Mother Island), the second largest of the Ogasawara Islands, some 1,000 kilometers south of mainland Tokyo. Here, tour-guides-turned-farmers Taeko Morosawa and Toshinori Konishi teach visitors about sustainable farming and conservation through tours and hands-on experiences with local farmers such as Kazuo Orita, who had kindly offered me the mango.

On Ogasawara Islands' Hahajima, operating Taekoni Farm and guiding tours: (left) Toshinori Konishi and (right) Taeko Morosawa.

“Mangos are not usually part of the tour,” Morosawa says, laughing. “But Orita sometimes gives them out—especially when he’s in a good mood.”

“You can just throw the skin over there,” Orita adds. “The birds will eat it.”

On cue, a couple of small green and yellow songbirds fly by and Morosawa tells me they’re Hahajima meguro and are designated as a Japanese national natural monument. “They’re found nowhere else on Earth,” she says.

World Natural Heritage Site

Around 400 residents live on the island of Hahajima in the Ogasawara Islands (as of August 1, 2025).

The Ogasawara Islands (aka Bonin Islands) are a side of Tokyo few inbound tourists know exists: a UNESCO World Heritage Site with forests that are home to unique species of plants and animals. It is a place with hidden beaches, and water so clear and blue it seems unreal; where you can dive with dolphins and green turtles year-round, or watch whales frolic among the waves in the early spring.

But reaching Ogasawara takes commitment, and its remoteness keeps many away.

The only way to get to the islands is the overnight ferry from Takeshiba Wharf in Tokyo to Chichijima (Father Island), Ogasawara’s main hub. The 24-hour journey may seem long, but the voyage itself is rather special. A few hours after departure, as phone service drops away, passengers slowly enter holiday mode—heading to the seats on deck to watch seabirds chase flying fish, or to the lounge to relax with a drink. If the weather cooperates, evening on the sky deck offers one of the most dazzling star views in Japan, and waking up early for sunrise is a must. On arrival, most passengers stay on Chichijima to join diving tours, while those heading on to Hahajima must board a smaller ferry and travel two hours further south.

Of the many Ogasawara Islands, only Chichijima and Hahajima are inhabited.

This isolation has become Hahajima’s greatest protection from over-tourism.

“The boat to Chichijima only runs once every six days and has limited capacity,” says Morosawa, “and it takes an additional one to two hours by boat to reach Hahajima. So we never have to worry about being overwhelmed by visitors. Those who do make the journey stay at least three nights, which allows them to truly understand and appreciate the islands.”

Taekoni Farm offers a range of tours and experiences for visitors that do make the effort to get to Hahajima. These include guided hiking and trekking adventures through endemic forests to scenic viewpoints, or sightseeing tours by car, covering the island’s natural beauty and historical sites.

The 6-hour trek to Chibusayama (Breast Mountain) is a favorite of Morosawa’s. “It’s hidden by clouds now,” she says, pointing out the low clouds formed by the humid winds blowing in off the ocean. “But this mountain, with its endemic land snails, is why the area became a World Natural Heritage site.”

This endemic snail species contributed to the Ogasawara Islands being designated as a UNESCO World Natural Heritage site.

During these hikes the pair takes special care to prevent the spread of invasive species that could threaten the island’s natural treasures. “If we’re moving between mountains, we collect plant seeds that might be on our clothes when we move, or animal eggs,” explains Konishi. The island’s red soil also creates problems because it sticks to shoes. “We’re careful to use mud-removing mats,” he adds. “And make sure that our customers are careful too.” Tokyo Metropolitan Government rangers also ask visitors to clean their shoe soles when boarding boats traveling between the islands to prevent contamination.

For those who choose not to stay overnight on Hahajima, there are short cultural experiences such as island folk song ukulele lessons and traditional craft workshops, and hands-on agricultural experiences making lemon jam and cacao nibs.

Making jam from lemons harvested at Taekoni Farm.

“The experience program typically runs 1.5 to 2 hours,” says Morosawa. “For day-trippers from Chichijima, it works perfectly. We start around 10 a.m. and finish around 11:30, which gives them time for lunch, visiting local museums, and swimming before they have to return. It gives them a chance to experience the slower pace that’s more characteristic of Hahajima than a rushed tour that ends 30 minutes before the afternoon ferry leaves.”

From Crisis to Opportunity

(Left) Kazuo Orita and (right) Taeko Morozawa of Taekoni Farm.

The idea for Taekoni Farm was born during the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. Like much of the world, Ogasawara completely shut its borders from April to June, and tourism disappeared, seemingly overnight. Morosawa, then working at the Hahajima tourism association, and Konishi, working as a guide, suddenly had unexpected free time. “Orita-san asked if we wanted to help grow watermelons since we had time,” Morosawa says. "And we found that working in the fields, touching the soil, and seeing the beautiful scenery was incredibly healing during that stressful period.”

She realized that her feeling of connection to the land was something visitors should also experience. “They can do more than sightseeing,” she says. “They can learn about the island and get an emotional connection through agricultural activities.”

(Left) Konishi explains how to clean shoe soles at the entrance to the protected area.

(Right) A cleaning mat and vinegar spray for shoes are some of the measures to help protect the ecosystem.

Building Community Through Collaboration

Front of the container adapted to house the kitchen and workshop.

Before settling on Hahajima, they both lived in Tokyo, where Konishi was a systems engineer and Morosawa worked in biotech research. A particularly cold winter in 2013 pushed her to seek work somewhere warmer, and Konishi followed. “I realized if I didn’t make a change then, I never would,” says Morosawa. “I started looking for jobs on southern islands and found a position with the Hahajima Tourism Association.” She went on to spend eight years there coordinating with travel agencies and government bodies.

Taekoni Farms' success rests on the community ties the pair have made during their 13 years on Hahajima, especially with Orita, whose family has been on the island for generations. “Without him, we never could have succeeded here,” Morosawa says.

Their first meeting was memorable. She tried to hand Orita a whale-shaped banner at the port during the traditional farewell given to the ferry each day. When he gruffly dismissed it as a koi-nobori (carp streamer), she corrected him. It was a kujira-nobori (whale banner), she said, a symbol of the island. Somehow, that sparked a friendship that led to their working together.

Orita taught them how to farm on the island and now shares access to his cacao greenhouses, shima (island) lemon groves, and mango trees. The cacao operation originally began in 2011, when the Saitama-based Hiratsuka Confectionery Co. sought farmers to grow cacao in Japan and partnered with Orita to produce “Tokyo Cacao.” When the project ended this year, Orita inherited the greenhouses and trees. He now shares the facilities with Taekoni Farm, which uses them as the base for their “Farm Tour and Island Lemon Jam and Cocoa Nib Making Experience.”

(Left) Cacao pods grown on Hahajima, filled with beans that become the base of chocolate.

(Right) Fermented and roasted cacao beans, crushed into cacao nibs — the starting point of chocolate.

The couple also collaborates with other island guides to minimize the strain on the island’s limited resources. “Hahajima has very few guides,” Morosawa says. “By working together and sharing facilities, we can offer more diverse experiences while reducing our individual environmental footprints.”

Their approach emphasizes visitor comfort and environmental responsibility. “We want visitors to Hahajima not just to come, sightsee, and leave, but to have a place where they can truly learn about, savor, and feel this island,” Konishi says.

Guided experiences deepen visitors’ understanding of Hahajima’s nature.

“The most important thing is to make sure that customers have a comfortable stay. For example, we remove all the tedious parts of the cooking experiences—everything is pre-measured and prepared. Customers should only experience the fun parts and leave with happy memories.”

Up until now the only thing that’s prevented that from happening has been the weather.

Sustainable Adventures in All Weather

The facilities at Taekoni Farm, designed to allow experiences even on rainy days, are steadily nearing completion.

In the past, they’ve had to cancel or move activities because of sudden heat waves or typhoons. “On Hahajima, the weather shifts quickly, and the humidity is extreme,” says Konishi. Even in winter we need to run dehumidifiers all the time. But with the all-weather space we’re building, we can finally offer stable, year-round experiences.”

The project, funded by a grant from the Tokyo Convention & Visitors Bureau, is set to become the centerpiece of Taekoni Farm when it opens in late August 2025.

As we finished our visit to the cacao farm, Morosawa and Konishi showed me the refurbished shipping containers that will make up the new facility. Painted a cheerful light blue to stand out against the jungle, they feature wide windows that will overlook both the farm and the ocean beyond.

Visitors will be able to join various experiences that will be offered in these containers.

“The facility is designed to handle rain and wind, but also heat like we’re experiencing today,” Konishi says. “It has wooden deck areas outdoors, so we’ll be able to use the same space year-round, whether it’s a sunny or rainy day.”

The design serves several other purposes beyond comfort. When hikers trek during wet conditions they may veer off path to avoid the mud, which can cause trail degradation. Alternative activities, such as those provided at Taekoni’s new facility, can reduce trekking during bad weather and protect the mountains from erosion. The new buildings also provide a permanent base that removes the need to transport equipment for each tour.

The farm includes greenhouse facilities, allowing visitors to enjoy harvest experiences even on rainy days.

Later, onboard the departing ferry, I watched the locals wave farewell with the traditional kujira-nobori, while someone drew a giant whale with water on the concrete wharf. Seeing the delight in the faces of the families beside me on the boat, I thought about something Konishi had said.

A whale painting drawn with water.

“We want families with small children to come,” he said. “Some tour operators don’t accept them, but we believe childhood experiences are crucial. We often meet people who say, ‘I came here decades ago,’ and find that those early memories are what brought them back.”

Perhaps what we need are more places like Hahajima and Taekoni Farm—remote enough to slow us down, remarkable enough to make the journey worthwhile, and sustainable enough to ensure they’ll be there for many generations to come.

Among the numerous tours Konishi and Morosawa have led are tours for blind guests, featuring activities focused on the sound and sensations of the natural environment: wind, birdsong, and the sound of waves.

Taekoni Farm

Location: Hahajima, Ogasawara Village, Tokyo [MAP]

Access: Takeshiba Pier → (Ogasawara-maru, approx. 24 hrs) → Chichijima → (Hahajima-maru, approx. 2 hrs) → Hahajima

Experiences: Farm tours, food processing workshops (see website for details and pricing)

Reservations: Via the official website’s booking form

URL:https://poco.taekoni.com/

SNS:Instagram https://www.instagram.com/taekonifarm/

Sustainable Traveler: Andrew Lee

Andrew Lee is a writer with extensive experience in the publishing industry. He spent 10 years at The Japan Times, where in 2017 he led the rebranding and redesign of the newspaper. He has written numerous travel articles on Japan’s nature, culture, and cuisine, always drawing on firsthand visits to showcase each region’s unique appeal. He also brings a wealth of reporting experience and insight into sustainable tourism.

※This content was produced with support from the Tokyo Convention & Visitors Bureau Sustainable Travel Promotion Grant Program.