Water, Rocks, Plants, and More: Five Types of Japanese Gardens

Japanese gardens are everywhere in Japan from the biggest cities to the smallest towns. While many enjoy strolling through these green spaces, how often do we take note of the different styles and meanings that lay in their roots? Here is Elizabeth Sok's overview of the history, characteristics and prime examples of five styles of Japanese gardens!

By Elizabeth SokA Brief History of Japanese Gardens

Japanese gardens have long captured the imagination of admirers. Japan’s first novel and one of the oldest in the world, The Tale of Genji, spotlights the importance of Japanese gardens in the dramas of court life. Gardens have also long been promoted as key spots for tourism. Since at least the turn of the 20th century, for instance, Kenrokuen (Kanazawa), Korakuen (Okayama) and Kairakuen (Mito) have been considered the Three Great Gardens of Japan. All were featured together in a 1904 brochure aimed at incoming overseas tourists and continue to appear as top destinations for visitors today.

Japanese gardens have existed in some form since the fifth century. The oldest ones recorded in historical documents, but lost to us today, date back to the earliest incarnations of the Shinto religion. Areas teeming with spiritual power, such as trees, mountains and other natural elements were demarcated with pebbles. These stones marked the boundaries between the human and divine worlds and are considered to be examples of early Japanese gardens. While these proto-gardens don’t exist anymore, their remnants can still be seen today, as in the pebbled areas in the East Palace Garden of the Nara Palace Site.

East Palace Garden of the Nara Palace Site

As Buddhism began to spread in Japan in the sixth and seventh centuries, so too did its influence on Japanese aesthetics. Gardens built on the grounds of the nobility and near Buddhist temples tended to be large and contained several key elements, including ponds big enough for boats, hillsides, islands and streams throughout. Kyoto’s Shosei-en Garden maintains one of these large ponds which covers about a sixth of the total area. Except for a few examples from archaeological excavations or later gardens, none of these early Japanese gardens survive in their entirety.

Over the centuries, Japanese garden designs have blended influences native to the archipelago with cultural imports from overseas. In the rest of this article, we’ll see how these ideas have been shaped into five types of Japanese gardens that you can visit today.

Karesansui: from stones to natural landscapes

Ryoan-ji's stone garden (Kyoto)

Originating near the end of the Heian period (794-1185), karesansui, also known as Japanese dry, rock, or Zen gardens, are a unique type of garden in which landscapes are depicted using sand and stones. Karesansui gardens became popular during the late Muromachi period (1336-1573) and were commonly built by temples and monasteries to visually express Zen Buddhist philosophy.

Karesansui gardens were constructed to be relatively small and were usually surrounded by buildings or stone walls. These gardens were not designed for strolling, but created as sources of contemplation to facilitate Zen meditation. Karesansui gardens were meant to be quietly admired from a central viewing spot, such as on the porch of a hojo (a Buddhist monk’s hall). The compositions of karesansui gardens were carefully arranged to mimic natural scenery, such as large standing rocks to portray hills or mountains and white sand or gravel to imitate water.

A dry garden in Nansen-ji (Kyoto)

White sand or gravel has long been a sign of purity in the Shinto religion and, as we saw earlier, often denoted the borders between the human and the divine. So, in this way, Karesansui blend together Shinto and Buddhist ideologies. But, in Zen gardens, compared to the pebbles of early Shinto, the white sand is meticulously raked into a variety of ripple patterns to represent emptiness, like the white space around a painting. Perhaps the most well-known examples of Karesansui gardens are located at Ryoan-ji, Daisen-in, Nanzen-ji and Ginkaku-ji Temples in Kyoto City.

Chaniwa: a quiet place to enjoy your cup of matcha

Rakusuien (Fukuoka)

Tea gardens, known as chaniwa or roji in Japanese, refer to a style of garden which developed around tea houses used for tea ceremonies. Initially created in the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573-1693), when Sen-no-Rikyu developed the tea ceremony based on Zen Buddhism, chaniwa were the first Japanese garden to embody the expectation of a stroll or walk through. The Tea Garden’s second Japanese name, roji, refers to a pathway towards spiritual enlightenment. Meant to cleanse your mind on the way to the tea house, these gardens were originally only found adjacent to Buddhist temples.

The key characteristics of this garden lie in its rustic simplicity and lack of ornamentation. In their most traditional form, no brightly flowered plants or trees that change color in autumn were chosen to distract from the quiet garden path. Perhaps the main feature is the pathway to the tea house, usually made of stepping stones left in their natural shapes and lit by a lining of Japanese lanterns. While the pathway and lanterns are now considered typical of most Japanese gardens, they began here in the chaniwa, as a gentle guide away from the bustle of the world towards the solemnity of the tea house. Another important element is the stone basin or tsukubai, where guests are expected to rinse their hands and mouths before entering the sacred space of the tea ceremony.

A beautiful example of a chaniwa or roji is in the Myoshinji temple complex in Kyoto. There, at a smaller sub-temple called Daiho-in, in the autumn and spring, you can enjoy a cup of green tea at the tea house while overlooking the roji. Fukuoka City’s Rakusuien is also a charming example of a small chaniwa, stately in all four seasons, with a tea house accessible to the public.

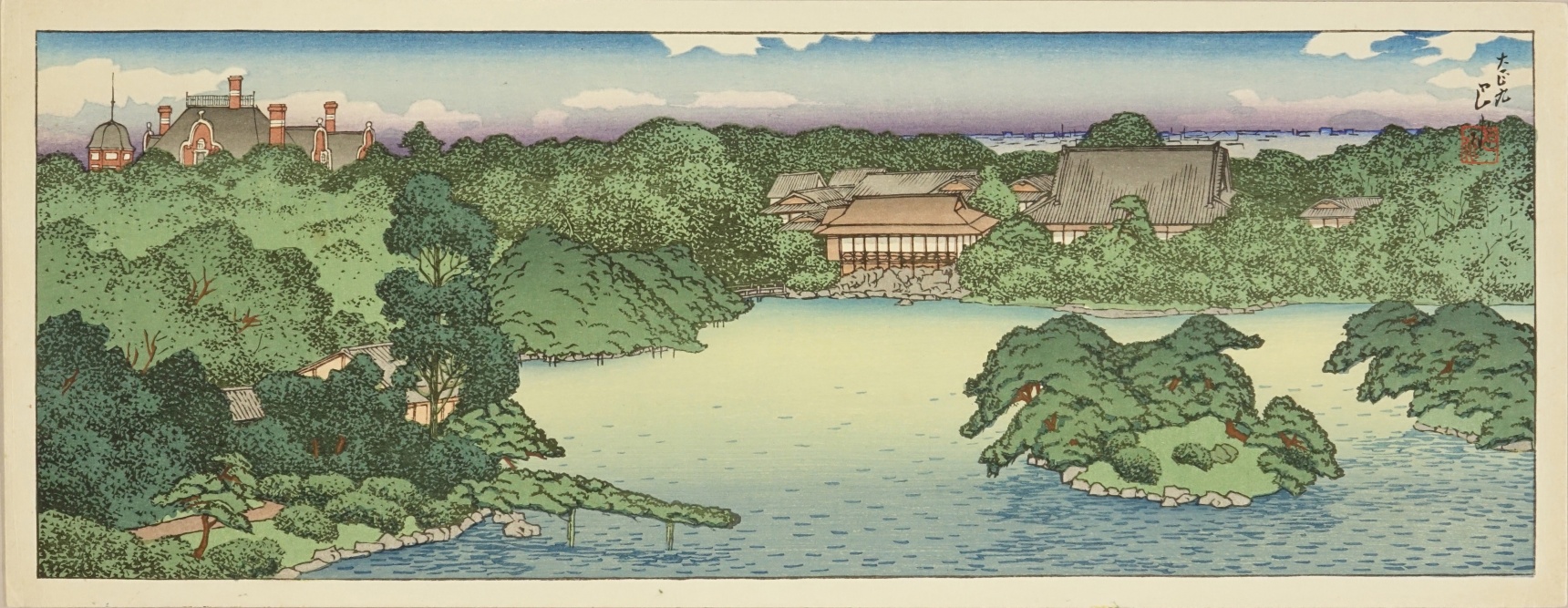

Kaiyu shiki teien: stroll through Japan without leaving the garden

Korakuen Garden (Okayama)

Kaiyu shiki teien, or stroll gardens, are often considered the culmination of Japanese gardens in that they combine elements of earlier styles. Originally built around Zen temples in the Muromachi period (1336-1573), these gardens are thought to have reached peak construction during the Edo period (1603-1868). Spreading from the temples to the nobility, the daimyo (feudal lords) in Edo built them as part of their lavish residences, giving rise to their alternative name, daimyo teien (Daimyo gardens). Japanese strolling gardens served to showcase a daimyo’s wealth and prestige. For this reason, they were often quite large, with some ranging from 50,000 to 100,000 square meters.

There are various types of Japanese strolling gardens built by temples and daimyo, but the most common style is the chisen kaiyu shiki. This garden consists of a large pond in the center, usually sizable enough to accommodate pleasure boats, surrounded by a network of walking paths. There are also miniature hills, small islands, curved bridges and large iconic stones placed throughout the garden. Garden designers also sought to bring famous scenery into the garden, such as creating artificial hills to mimic the appearance of Mount Fuji. Another feature of these gardens is that they typically have pavilions and tea houses which serve as both resting places and observation areas from which you can view the garden.

Overall, these gardens are stunning to behold. One needs look no further than the so-called Nihon-santei (Japan’s Three Great Gardens), introduced above, which are all stroll gardens.

Tsuboniwa: urban oases with a practical purpose

Tsuboniwa refers to small enclosed gardens that were features of palace courtyards beginning in the Heian period. These gardens eventually gained popularity among merchants in the Edo period who built them between their shops. Tsuboniwa were particularly prominent in Kyoto, where the grid-like street organization resulted in narrow plots of land on which merchants could build their machiya or traditional Japanese homes. Given the cramped conditions, tsuboniwa were placed at the back of these homes and provided a much needed urban oasis that doubled as sources of light and ventilation. Nowadays, these gardens continue to be attractive additions to homes, restaurants, hotels and shopping centers.

The term tsuboniwa originates from the traditional unit of measurement known as the tsubo which measured about 3.3 square meters and niwa meaning garden. As the name implies, these gardens are designed to be small and are not meant to be walked through, but rather viewed from the indoors. Tsuboniwa are often placed in inner courtyards and enclosed spaces within homes and restaurants, where they can be observed while eating. Tsuboniwa typically include a small number of plants, especially shade-loving varieties like moss or ferns given the reduced lighting available. These gardens commonly contain sculptures like stone lanterns, large ornate stones, a water basin for cleansing one’s hands and white sand or gravel that is carefully raked and kept free of weeds.

Kyoto remains the center of tsuboniwa culture with many gorgeous examples in restaurants, inns and private homes. Check out Machiya Residence Kyoto, where you can rent small Kyoto houses, for some truly beautiful examples.

Blending Traditions: Modern Fusion Gardens

Sorakuen (Kobe)

In the Meiji period (1868-1912) and beyond, many modern gardens which opened to the public combined elements of the Japanese gardens above and added features of western-style gardens. For example, some of these contain a lawn or bed of flowers in addition to a strolling garden while others include both a Japanese tea house and western-style brick buildings. Many of these gardens were created with the support of private families or government initiatives towards westernization and tourism. Tokyo, the site of the new capital in Edo and center of much modernization in the Meiji and Taisho (1912-1926) period, is home to many of these Japanese and western mixed gardens.

Since the structure of these gardens are so diverse, it is easier to imagine them by describing famous ones. Tokyo’s Kyu-Furukawa Gardens are one lovely example. Originally the home of a notable Meiji era family, the English-style residence and garden were designed by famed architect Josiah Condor while the Japanese garden was designed by the renowned Kyoto designer, Niwashi-Ueji. The juxtaposition between the western mansion and rose garden, and the Japanese tea room, lake and strolling garden, is at the heart of what makes these modern fusion gardens so stunning.

Kobe’s Sorakuen Garden is another example that blends Japanese and Western influences. Once owned by a former mayor of the city, it was opened to the public in 1941. While the original grounds included several Western buildings nestled in the Japanese style stroll garden, only one survived the bombings of World War II. After the war, several Western buildings were relocated to the park, including the former home of a local Anglo-Indian merchant.

Plenty more to explore!

Ritsurin Garden (Kagawa)

Whether you’ve visited dozens of Japanese gardens or are looking to stroll through your first one, we hope you’ll be able to appreciate them a little more. Of course, there are many types of Japanese gardens beyond this list and there are nuances even within these examples. After you’ve visited some of the gardens we’ve highlighted, here are a few more:

- Ritsurin Garden (Kagawa Prefecture): a large kaiyu shiki teien-style garden often mentioned alongside Japan’s Three Great Gardens

- Saiho-ji Temple (Kyoto Prefecture): a moss garden featuring over 120 kinds of moss and designated a Special Place of Scenic Beauty by the Japanese government

- Adachi Museum of Art’s gardens (Shimane Prefecture): awarded Japan’s best garden for 21 straight years and counting, this modern garden contains several elements from the history of Japanese gardens, including a tea garden, dry garden, pebble garden and more