Hakko Department: One-Stop Shop for All Things Fermented in Trendy Shimokitazawa

Tokyo’s Shimokitazawa is known as a trendy hangout for young people and creatives, popular for its second-hand and vintage clothes shops, Instagrammable snacks and sweets, and quirky businesses. Phoebe Amoroso introduces Hakko Department, a fermentation-focused store that forgoes the fads and draws on Japan's past to inspire the future.

By Phoebe AmorosoHakko Department—“fermentation department”—opened in 2020 as part of Bonus Track, an eclectic shopping area that came as the area was redeveloped by the Odakyu Corporation when it moved a major train track underground.

It’s part-shop, part-cafe, part-museum; a space dedicated to Japan’s fermentation culture and beyond. The shop stocks roughly 450 products from around the country, and even some from overseas. Beyond the classics of miso, soy sauce and sake, you can expect to find everything from black koji, a kind of mold for your own fermentation experiments to tofu-yo, a fermented tofu from Okinawa, or kanzuri, a fermented chilli paste from Niigata.

The products here are far from being randomly selected.

“There are three rules for how we choose what products we sell,” says Hiraku Ogura, Hakko Department founder and fermentation evangelist.

“Our team members must have gone to the place that makes the product and met the producers. We apply this rule for products from abroad too, so we do travel overseas.”

The next rule is that the product must be as close as possible to the way it was originally made, with added amino acids, sugars and other things kept to a minimum. And the final rule—and this is quite important, Ogura says—is that the team chooses products that match with the modern diet. They even go as far as developing recipes and serving suggestions.

“If we only preserve the traditional way of doing things, these products won't be used any more. Even if the production method is traditional, the item is being used in the modern environment,” Ogura says.

“If we only preserve the traditional way of doing things, these products won't be used any more."

Outdoor natto—fermented soy beans designed for camping and picnics. Simply squeeze them out the packet.

Ogura himself was late to the world of fermentation, having grown up with little interest in food or nutrition. Starting out as an art director, his role was to solve problems through design, leading him into the world of social enterprise, including working on regional revitalisation projects. Even as he visited dying villages, plagued by rural-to-urban migration and an ageing population, he was impressed by the ongoing importance of local soy sauce and miso factories or sake breweries.

It was personal circumstances that were to push him either further down the fermentation path. He had suffered with asthma and allergies in his younger years and then these problems returned. A recommendation from a professor at Tokyo Agricultural University got him eating more fermented foods like miso and pickles, and his health improved.

“Fermentation changed my life,” he says with conviction.

Now, Ogura calls himself a member of the fermentation research society, determined to make the world a better place through the power of mold and microbes.

"Fermentation changed my life."

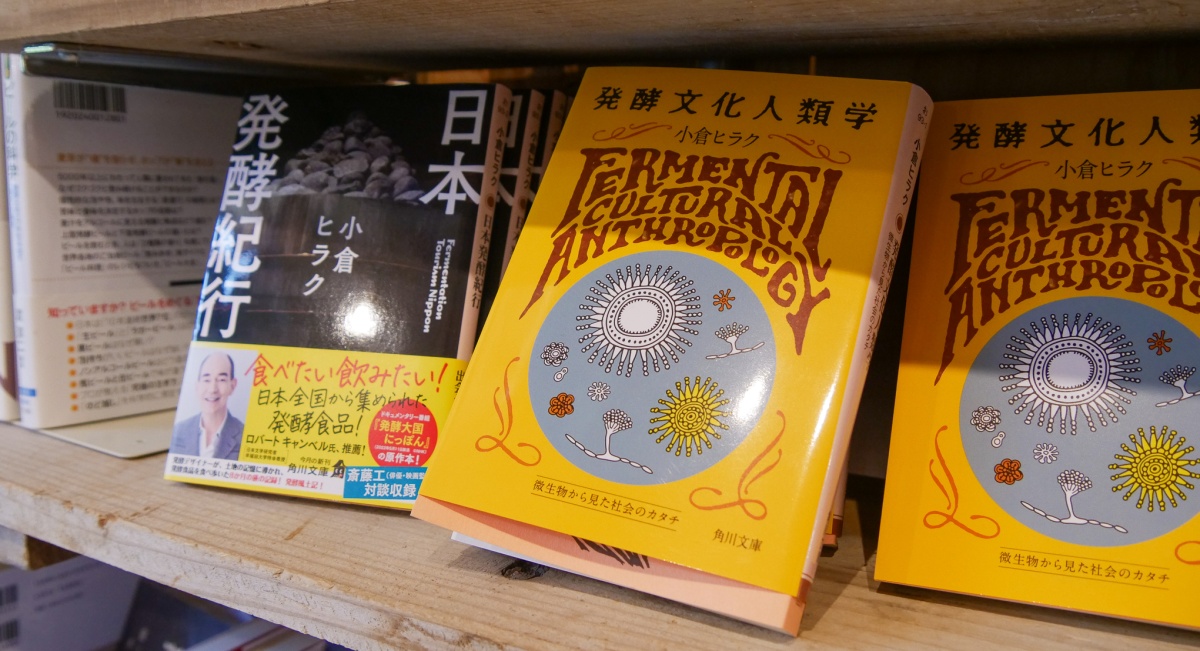

Ogura's book Fermental Cultural Anthropology brought him wider recognition for his work

It has been a long road. When he first started out 15 years ago, he struggled to attract interest.

“I think people just thought of fermentation as something traditional, or they had an image that it was something aimed at old people,” he says.

The Tohoku tsunami, earthquake and nuclear disaster in 2011 was to change that. Severe disruption to the country’s food supply and fears over food safety prompted the younger generation to take a greater interest.

“Young mothers started coming to my workshops,” Ogura says. “Up until then the focus had been on good value food items that were also delicious but, from that time onwards, people began to think about the safety of their food. People started questioning where the food they were eating had come from and how it was made, and they realised they didn’t know and started to feel uneasy about that.”

Roughly five years later came a different shift that he calls the “beauty boom.” This saw fashionable, health-conscious young women looking to improve their gut microbiomes and internal systems in the hope for an improvement in their outward appearance.

For Ogura, more widespread recognition of his work finally came in 2017 when he published the book Fermental Cultural Anthropology, which sold well and was subsequently translated into Korean and Chinese. It was around this time that he felt some of the generational and gender divides began to dissipate and fermentation began to permeate the wider public consciousness.

Fermented products from Japan's 47 prefectures

In 2019, he was invited to exhibit at d47 Museum in Shibuya, which showcases design products from Japan’s 47 prefectures. The concept was "Fermentation Tourism Nippon—Rediscovering Japan through Fermentation.” This was accompanied by a challenge: they had to choose fermented products from each of Japan’s 47 prefectures, but none of them were to be repeated.

“It would be an easy win to repeat sake and soy sauce, and that would be no fun, so we made the rule. But it was really hard,” he says.

Ogura and his team travelled Japan extensively to track down products, visiting villages where only a few elderly members of the community were making a fermented foodstuff that no-one outside the immediate vicinity knew.

The resultant exhibition was a hit, and it led to him being invited to open Hakko Department as one of the flagship stores at Shimokitazawa’s new Bonus Track development in 2020.

Veggie tantanmen made with miso, tamari soy sauce and kanzuri fermented chilli paste

Now, Hakko Department is the go-to space for people wanting a taste of the fermentation lifestyle. As well as selling DIY fermentation kits to aspiring home-fermenters and stocking hundreds of books on the topic, it serves as a venue to workshops and other events. The cafe serves up healthy yet hearty lunches—some boasting foodstuffs fermented on site—or otsumami, light snacks to pair with a selection of sake that lines temptingly transparent refrigerators.

Yet Ogura says the development is having a ripple effect beyond its trendy western Tokyo setting, inspiring visitors to visit the origins of the products. That, of course, was precisely his aim—to help revitalize rural economies through fermentation tourism. Fermented products, he argues, are a living museum, a doorway into understanding regional culture and the history of a place and its people.

Yamaroku soy sauce made in traditional wooden barrels

The Hakko Department team is busy developing regional tourism programs. The d47 exhibition continues to tour. Last year, they exhibited in a tourism information centre in Fukui on Japan’s western coast, tying it to several local tourism itineraries and experiences. People were encouraged to visit local sights or take part in local culinary workshops, for example, making heshiko, fish pickled in rice bran. They hope to expand their activities further, working on regional revitalization through fermentation.

Ogura has several missions, beyond fostering deeper regional connections. He wants people to have life-changing experiences through connecting with fermentation, strongly advocating the joy and empowerment of making fermented foods oneself. He also aims to make Japanese fermentation culture globally accessible, to share ideas with different cultures overseas, and to develop it collectively.

“I want to make the culture of fermentation an asset for all humankind.”

Hakko Department

Shop: Daily, 11am - 8pm

Cafe: Mon - Sat, 11am - 4.30pm (last order 4pm); Sun, 11am - 7pm (last order 6pm)