The Life of Hokusai, As Seen in the Collection of a Remarkable Museum

"Under the Wave Off Kanagawa" by Katsushika Hokusai, from the series "Thirty-six views of Mt. Fuji," 1830-34. Oban nishiki-color woodblock print.

By Alice GordenkerYou have no doubt seen the image above, the iconic view of a huge wave that seems about to crash on Mt. Fuji. You probably also know that it was created by Hokusai, one of the very few Japanese artists to have achieved and maintained worldwide name recognition. But what else do you know about Hokusai, who changed his style as often as he changed his name? In this article, arts writer Alice Gordenker traces his journey while sharing a representative work from each stage of his prolific career, all from a single collection in Shimane Prefecture.

A Massive Collection of Remarkable Size

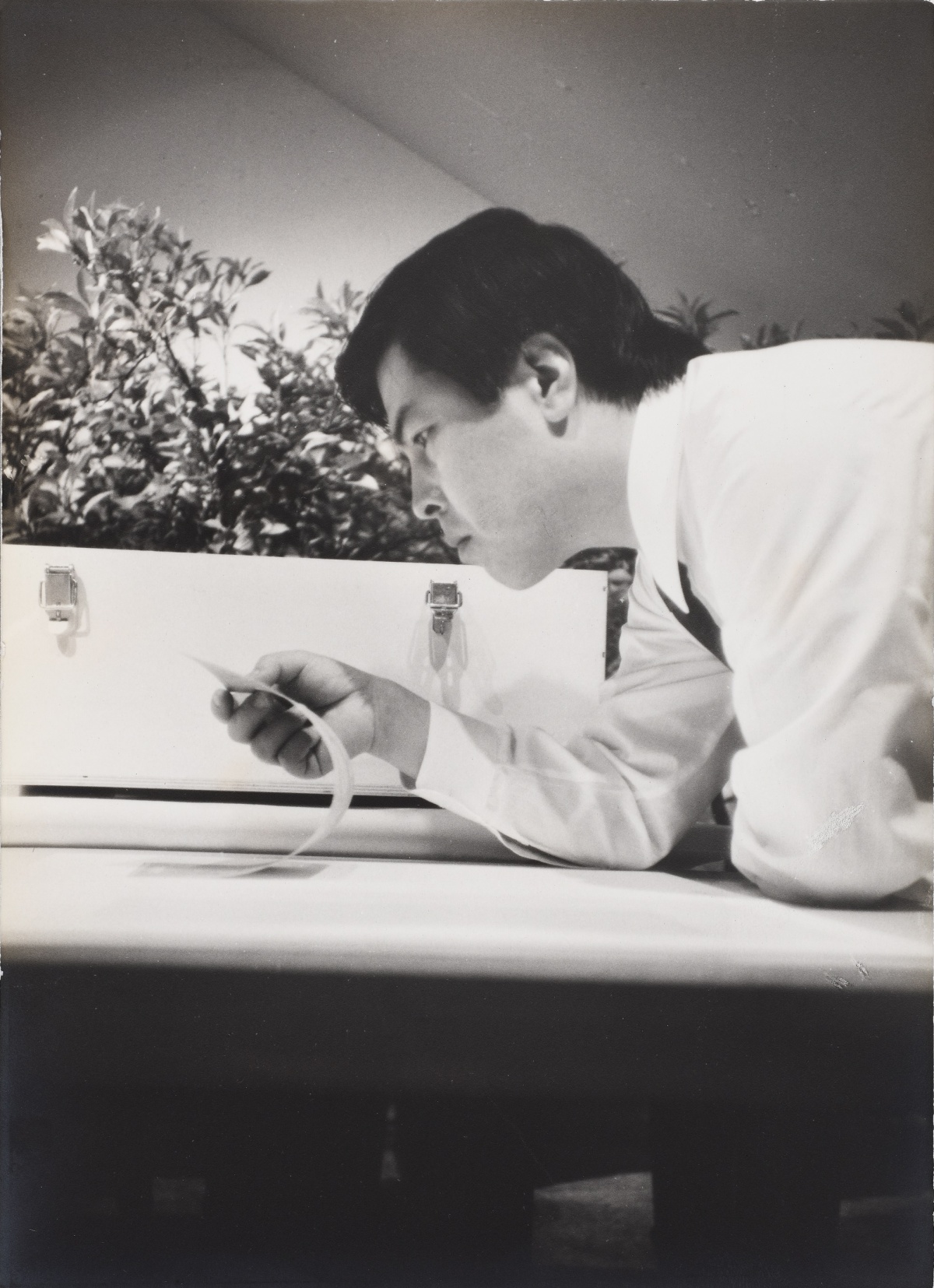

Nagata Seiji devoted his life to the study of Hokusai.

Hokusai’s works can be seen in museums around the world, including the British Museum in London and the Museum of Metropolitan Art in New York. In Tokyo, there’s even a newish museum dedicated entirely to the artist which opened in 2016 near his birthplace by the Sumida River. But of all the Hokusai collections in the world, the one at the Shimane Art Museum in Matsue is remarkable in quality and size—with over 1,600 works.

The collection was assembled by a Shimane native named Nagata Seiji (1951-2018) , who first encountered Hokusai’s work in a second-hand bookstore while still a child. Nagata went on to become both a collector and a prominent Hokusai scholar, making significant contributions to our understanding of the artist’s life and oeuvre. When Nagata passed away in 2018, he left his collection to his home prefecture. It includes outstanding and rare examples of Hokusai’s work that cannot be seen anywhere else.

Over the course of his lifetime, Hokusai is said to have used some 30 different names. While it was not unusual for Japanese artists of the time to adopt a new moniker, Hokusai changed names more often than most. In fact, his name changes are so frequent and so often related to changes in style, that they are helpful for understanding the arc of his career.

A Brilliant Start: Age 20 to 35

Tough-guy hero with demon: "Asahina Saburo Taira no Yoshihide," 1791-93. Chuban nishiki-e color woodblock.

The man we know today as Hokusai was born in 1760 in Edo (modern-day Tokyo) and given the name Tokitaro. His talent in drawing and painting emerged during his early years, and at the age of nineteen he was apprenticed to a painter and printmaker named Katsukawa Shunsho. A year later, in 1780, the young man made his debut as an artist in his own right when his master granted him the artist’s name of “Shunro.” Over the next fifteen years, he worked under this name, producing woodblock prints and paintings in a variety of genres covering subjects including kabuki actors, beautiful women, sumo wrestlers, and heroes from history. He also picked up the themes of popular spots in Edo, and even toys. Yet little of these early years remains; the Nagata collection includes the only known painting by Hokusai with his early “Shunro” signature.

Focusing on Luxury Prints: Age 36 to 44

"Turtles," 1798. Surimono color woodblock

At the age of 36, Hokusai changed his name from “Shunro” to “Sori,” and began to develop a more personal style. His focus at this stage was on a type of luxurious woodblock print called surimono. Commissioned by wealthy merchants, surimono were custom designs, made to order using only the finest pigments and paper, and were presented to friends and business associates on special occasions as a form of greeting or thanks. Hokusai made the charming print of turtles above for his own use, to announce yet another name change. Very few examples of this special surimono print survive, yet Nagata managed to find two copies and preserve them in his collection, now at the museum.

A Famous Illustrator of Novels: Age 45 to 50

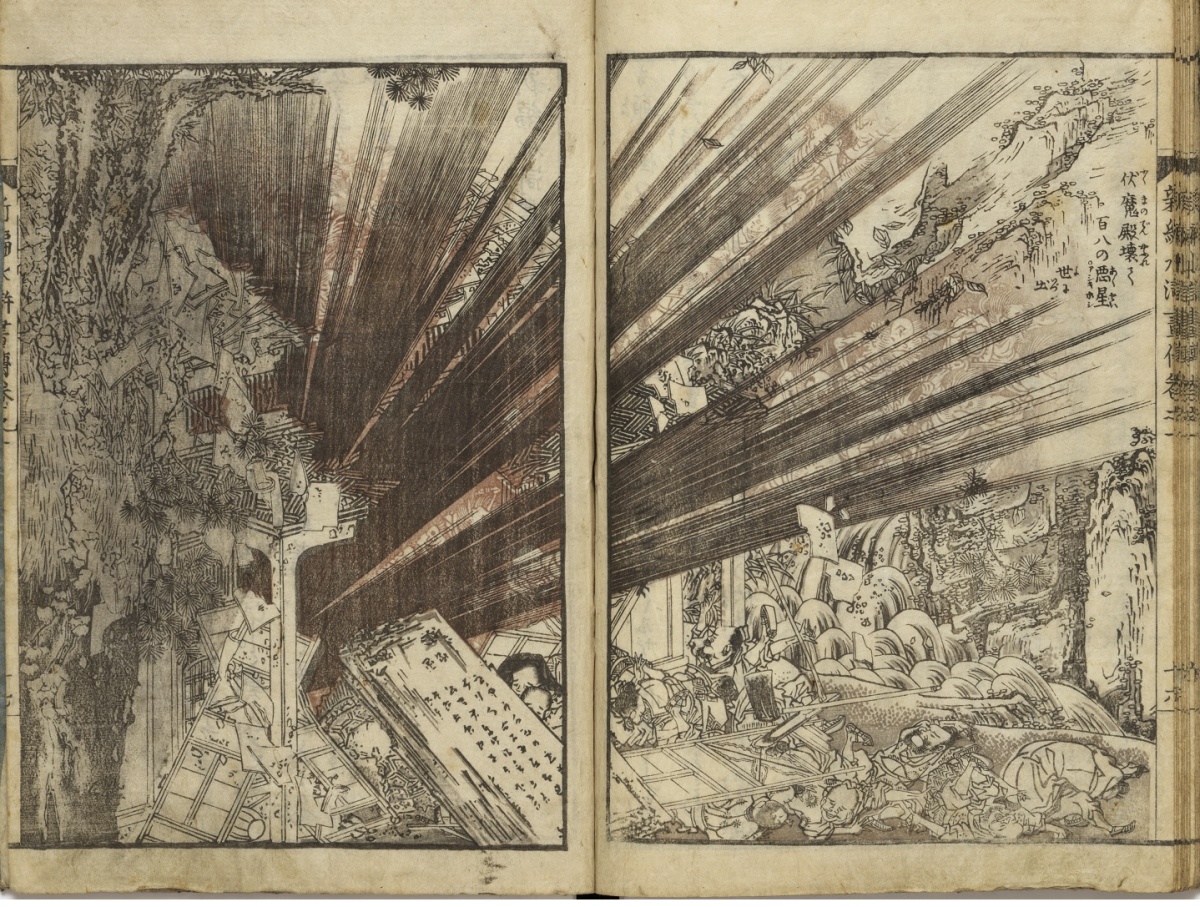

"Illustrated New Edition of Suikoden," (vol. 1), 1805. Printed paper book.

From about the age of 45, the artist began to work under the more familiar name of Katsushika Hokusai and launched himself in a new direction as an illustrator of printed stories. Hokusai contributed the illustrations for about 200 of these publications, which are known as yomihon and reproduced using woodblock prints. The stories were written by popular authors, but Hokusai’s dramatic imagery boosted sales and established him as one of the most sought-after illustrators of the day.

The scene above, from Hokusai’s illustration for a Japanese reworking of a classic Chinese story, uses radiating lines to express an explosion. It’s a device we’re all familiar with today, often seen in comic books and manga, but it must have struck readers of the time as startlingly original.

Master of his Craft: Age 51 to 60

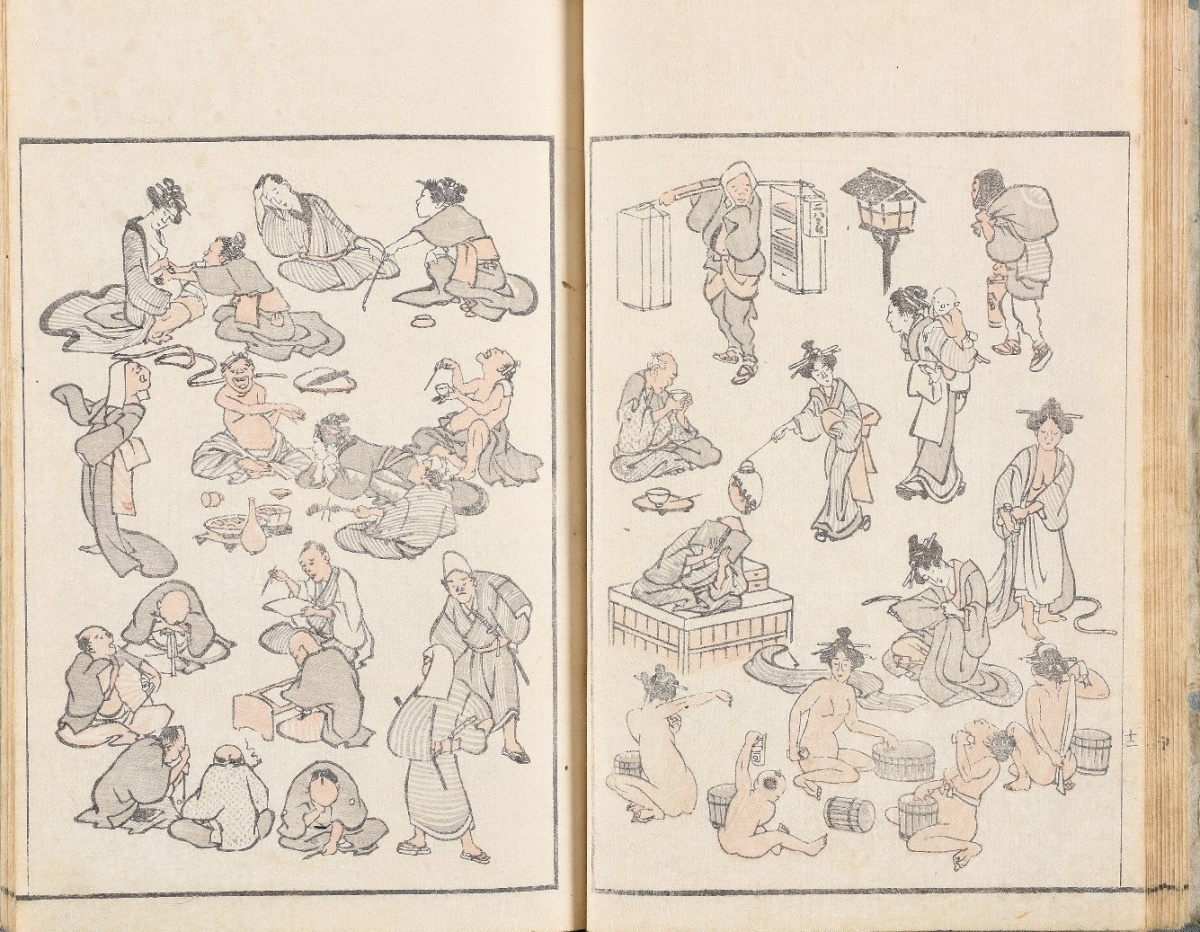

Hokusai sketches (Hokusai manga), vol. 1, 1814. Printed paper book.

In 1811, at the age of 51, Hokusai changed his name yet again, this time to Taito. By now, people all over Japan knew his work and wished to learn from him. He attracted far more pupils than he could accept, so he began to produce drawing manuals that anyone could use on their own. Known as edehon, these manuals demonstrated how to draw all sorts of subjects. The most famous of the drawing manuals are the “Hokusai Manga,” fifteen volumes that illustrate everything from people engaged in their various livelihoods to creatures of the sea. Although the title uses the word manga, these books had no storyline and were more like visual encyclopedias.

Worldwide Fame: Age 61 to 74

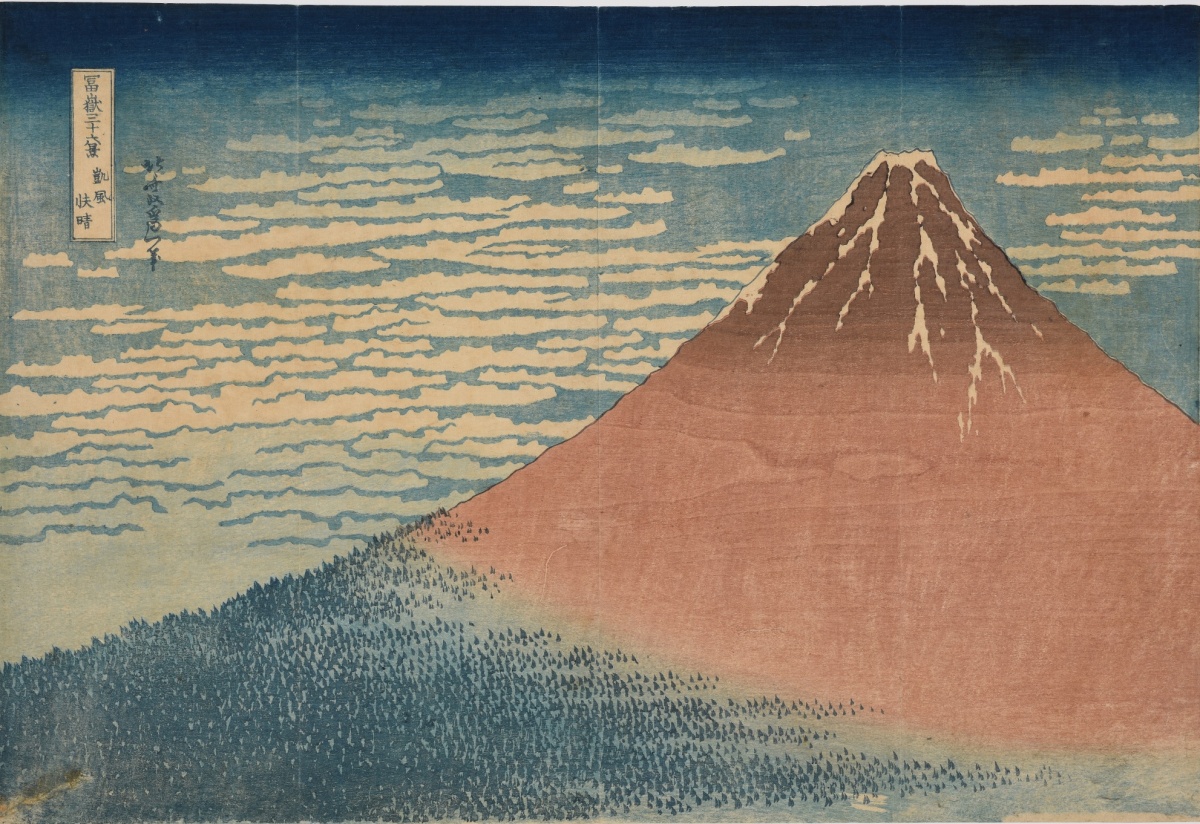

Popularly known as "Red Fuji," this famous image is actually titled "South Wind, Clear Sky." From the series "Thirty-six views of Mt. Fuji," c. 1830-34. Oban nishiki-e color woodblock.

Internationally, Hokusai’s best-known work is his “Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji” series, which—the title notwithstanding—actually consists of 46 prints. About 150 years ago, original copies of the prints were carried to Europe and North America where they inspired generations of artists and established Hokusai’s fame outside of Japan. The prints have become such symbols of Japan that they have been adopted for official use by the Japanese government: some of the images from the series now appear in the Japanese passport, and the new 1,000-yen bill, to be introduced in 2024, will feature “Under the Wave Off Kanagawa” on the back.

Crazy About Art: Age 75 to 90

“Salted Salmon and Mice.” Not a print but a painting, brushed in Hokusai’s own hand. From an album of paintings, c.1835-44.

From 1834, Hokusai began working under the name "Gakyo Rojin," meaning something like "Old Man Crazed About Art.” Despite his phenomenal successes, Hokusai wasn’t satisfied with his own achievements. Looking back at his life, and contemplating the future, he wrote:

“From the age of six, I had a passion for copying the form of things. Since the age of 50, I have published many drawings, yet of all I drew by my 70th year, there is nothing worth taking into account. At 73 years I partly understood the structure of animals, birds, insects and fishes, and the life of grasses and plants. And so, at 86 I shall progress further; at 90 I shall even further penetrate their secret meaning, and by 100 I shall perhaps truly have reached the level of the marvelous and divine. When I am 110, each dot, each line will possess a life of its own.”

In the spring of 1849, Hokusai died in Edo at the age of 90, having lived a life in which he surpassed his own personal best, under any name, again and again and again.

Dedicated Hokusai Gallery

Anytime you visit the museum, a good selection of Hokusai works will be on view. Photo by Alice Gordenker

The Shimane Art Museum building, constructed in 1999 and designed by prominent architect Kikutake Kiyonori, was recently renovated. The museum reopened in June 2022 with a dedicated Hokusai gallery, in which exhibitions are changed regularly so as much as possible of the collection can be shared.

Where, How and When to Go

Sunset at the Shimane Museum of Art on Lake Shinji. Photo by Alice Gordenker

Where

The Shimane Art Museum

1-5 Sodeshi-cho, Matsue

690-0049 Shimane Prefecture

+81 (0) 852-55-4700

How

The Shimane Art Museum is located in the city of Matsue in Shimane Prefecture. The closest airports are Yonago (served by ANA) and Izumo (served by JAL). The museum is a 15-minute walk from JR Matsue station.

When

Hours: October to February, 10:00 a.m. to 6:30 p.m., March to September, 10:00 a.m. to 30 minutes after sunset. (Daily times for sunset are posted on the museum website.)

Closed Tuesdays. If a national holiday falls on a Tuesday, the museum is open and closed the following day. The museum may also close for changes of special exhibitions so check the website when planning a visit.

Note:

If you can, time your visit for late afternoon. Although close to downtown and accessible on foot from JR Matsue station, the Shimane Art Museum is situated on a beautiful lake. It’s such a popular spot for viewing sunset that the museum graciously times its closing hours so visitors can enjoy both the art and the gorgeous vistas formed as the sun sets over the water.

All works pictured in this article are in the Nagata Seiji Collection. Except where otherwise stated, images courtesy of the Shimane Art Museum.

Other Articles on Japanese Art by Alice Gordenker

Why I Love Nihonga (and Want You to Love It Too)

A 'New' Museum for Your Kyoto Bucket List

Nine Treasures of Japan You NEED to See.

Winter at the Adachi Museum of Art: Superb Rosanjin Collection

California Transplant on Mission to Save Japanese Crafts