Why I Love Nihonga (and Want You to Love It Too)

Uemura Shoen, “Woman Waiting for the Moon to Rise” (1944), Adachi Museum of Art

Long-time Japan resident Alice Gordenker shares her appreciation of a genre of modern Japanese painting that captivates people all over the world with its rich natural colors, lyrical themes and surprising compositions.

Kawai Gyokudo, “Distant Thunder in Early Summer” (1952), Yamatane Museum of Art

My love affair with nihonga, a genre of modern Japanese painting, began with a casual invitation. My friend Carol, an art historian, asked me to join her on a visit to the Yamatane Museum of Art. This must have been at least twelve years ago, because the museum, which specializes in nihonga, hadn’t yet relocated to its current location in Hiroo. I can’t recall what the exhibition was, or even what we saw. Yet all these years later, I clearly remember feeling swept off my feet: in the rich colors and surprising compositions of nihonga, I had found the Japan of my dreams.

What is nihonga and why is it so captivating?

Although nihonga draws on the traditions of over a thousand years of painting in Japan, it is a distinct genre of modern Japanese painting that developed from around the turn of the twentieth century. At the time, Japan had only recently reopened to the West after more than 200 years of isolation, and many Japanese were seeing Western art for the first time.

Around 1880, the term “nihonga,” which translates literally as “Japanese painting,” was coined as a way to distinguish traditional methods of painting from Western oil painting. Soon, however, “nihonga” came to refer to a movement that arose among prominent Japanese artists and critics who were seeking to revitalize indigenous painting amidst the rising influence of Western art.

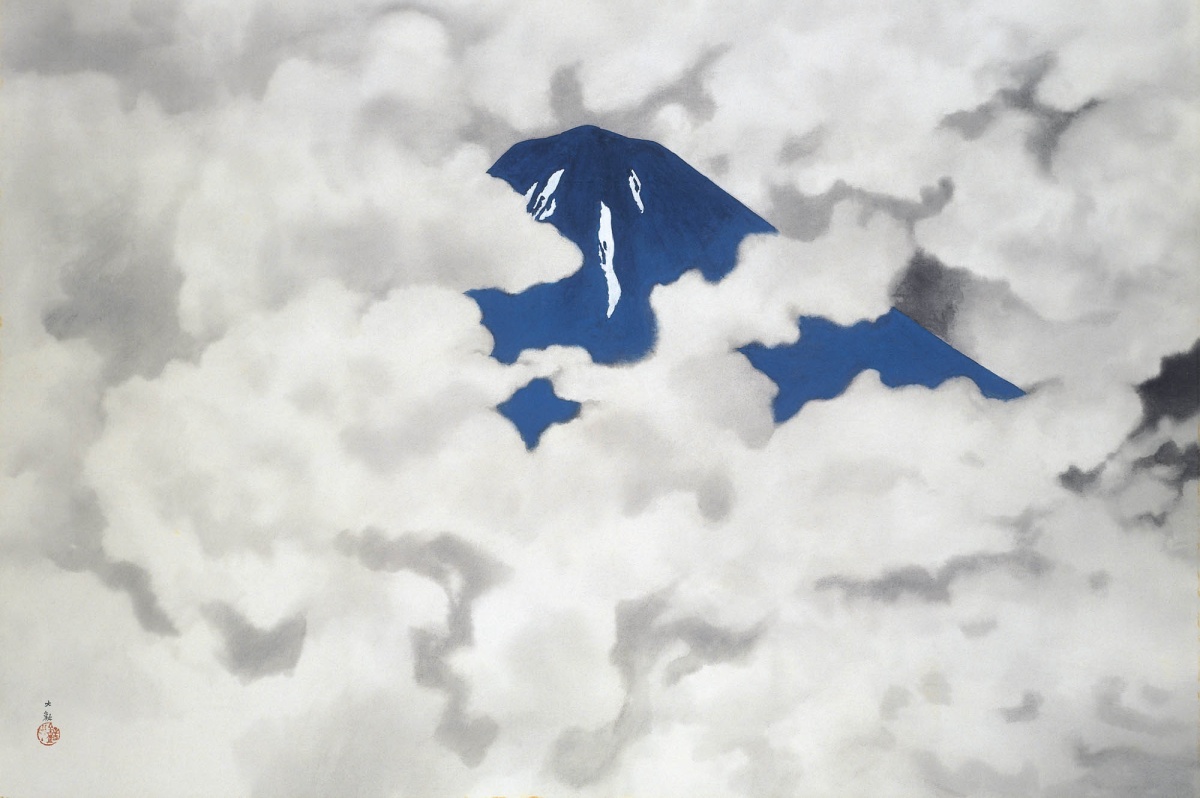

Yokoyama Taikan, “Four Seasons of Sacred Mt. Fuji, Summer” (1940), Adachi Museum of Art

A leading figure in this effort was Okakura Kakuzo, best known in the West for his 1906 treatise, “The Book of Tea.” In 1887, Okakura helped found the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, now called Tokyo University of the Arts and one of the finest art schools in Japan. Japanese painting was increasingly under attack as being flat and primitive compared to Western painting. The primary criticism was that it lacked the mechanisms used in Western art, including scientific perspective and chiaroscuro shading, that create dimension and variations in light. In response, Okakura challenged his students to develop original ways of expressing air and light. Rather than borrow from the West, he urged them to look within the traditions of China and Japan, so that their solutions might be authentically Asian.

Takeuchi Seiho, “Tabby Cat (1924), Important Cultural Property, Yamatane Museum of Art

Okakura was ousted from the school in an administrative struggle, but soon created a new institution called the Japan Arts Institute. Among the students who followed him were Yokoyama Taikan, Hishida Shunso, Shimomura Kanzan and Kimura Buzan, all of whom now rank among the most famous of nihonga painters. One approach the group tried was to do away with the strong outlines that previously characterized Japanese art. Instead, they used wash techniques to put down pigment in subtle ways so that colors or tones seemed to melt into one another without perceptible transitions, lines or edges. Shunso and Taikan, in particular, came to be recognized as masters of this highly atmospheric way of painting, and their works in this style are in the collections of top-notch museums around the world.

Hayami Gyoshu, “Two Themes on Insect Life: Spider's Trap Beneath the Leaves” (1926), Yamatane Museum of Art

Initially, the nihonga movement was consciously nationalistic, with proponents focusing in tightly on local landscapes and the beauty of nature close at hand. Many affiliated artists took up existing themes in Japanese painting, such as birds and flowers, and used the newly developed nihonga techniques to carry them forward in novel directions. Hayami Gyoshu, for example, created startlingly original representations of insects and spiders, while the female painter Uemura Shoen invigorated the long-established genre of Bijinga (depictions of beautiful women) with richer coloration and compositions distinguished by the bold use of empty space.

Today, nihonga has evolved into an international art form, adopted by artists of many nationalities working all over the world. Subject matter, too, is no longer limited to traditional Japanese themes. For these reasons, nihonga is now best defined by the very distinctive set of materials used.

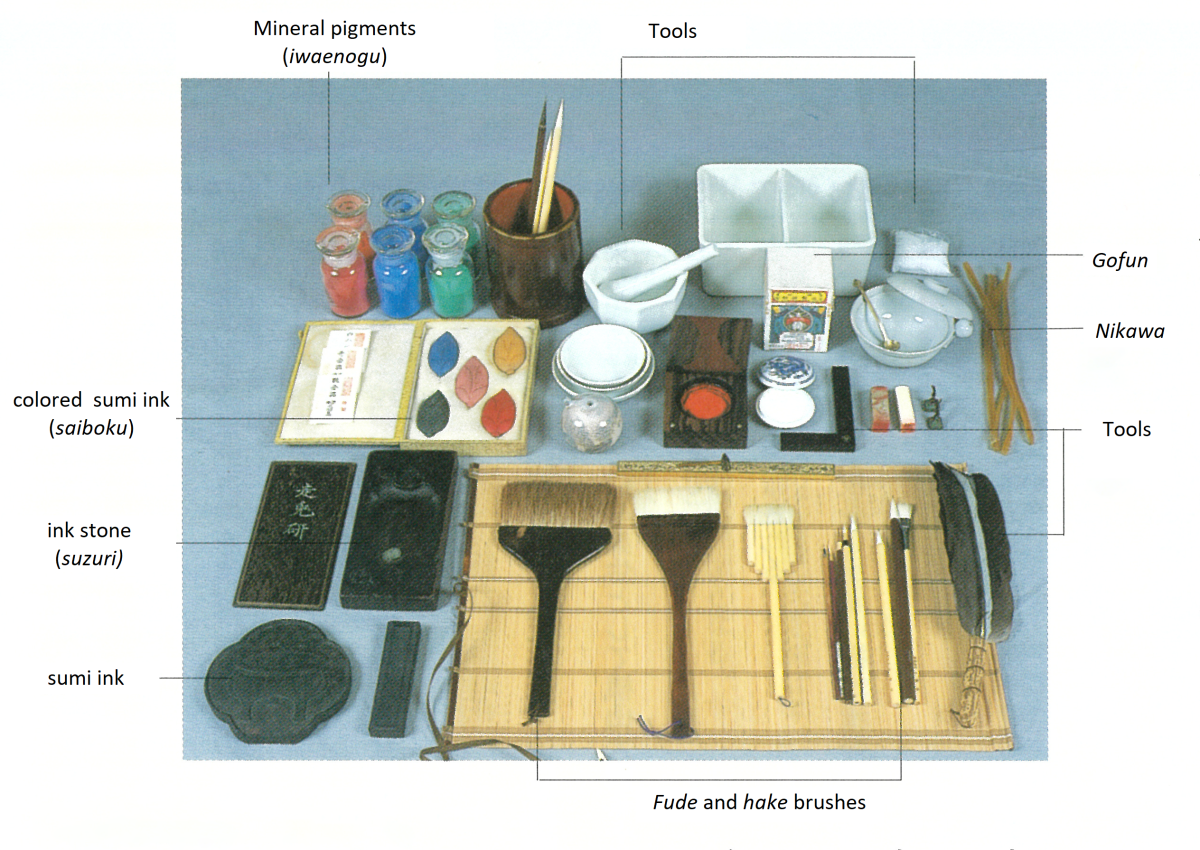

Tools and materials used in nihonga painting. Image courtesy of Tokyo University of Fine Arts and arts publisher Tokyo Bijutsu.

Silk, paper, gold and rocks

Unlike oil painting, which is most often done on canvas stretched on a frame, the support for nihonga is generally silk or handcrafted washi paper made with plant fibers such as mulberry and hemp. Paper is easier to work with, but the open weave of silk permits the use of special techniques such as applying pigment or even gold or silver leaf to the back of the composition to add richness or light.

The vibrant colors that are one of the hallmarks of nihonga come from special paints that must be prepared by hand immediately before use, mixing finely ground pigments with water and a special glue called nikawa as the adhesive. These paints take a long time to dry, so the support is placed flat before the artist, on the floor or a table, not at a slant on an easel.

Many of the pigments are rare and expensive, derived from semi-precious stones such as azurite, which creates a vibrant blue, and malachite for one of the many variations of green. Various clays and chalk are used for earth shades, and a beautiful white called gofun is made from shells. Traditional sumi ink is also widely used in nihonga, as are gold and other metals, which can be applied as paint, powder or thinly pounded metal leaf. Part of the power of nihonga comes from the inherent beauty of the materials themselves.

Konoshima Okoku, “Spring on a Main Road” (1913), Fukuda Art Museum

We’ve provided images with this article to help introduce nihonga, but a digital reproduction is never as good as the real thing. When you’re getting to know a potential love interest, there’s no substitute for spending time together, face to face. To experience the full depth and splendor of Nihonga, you need to see the paintings in person. To that end, I’m recommending a few museums with terrific collections. Go, and I’m betting you’ll fall as hard as I did.

Best Museums for Nihonga

Although many major museums in Japan organize limited-run exhibitions of nihonga, there are a handful of excellent museums where you can be sure nihonga will always be on view. Most are located in top destinations for foreign tourists, and are easy to build into a visit to Japan.

In Tokyo, the first museum in Japan to specialize in nihonga, and where I lost my heart. With over 1,800 works centered on modern and contemporary nihonga, this museum is noted for its extensive collections of works of individual artists, including 135 paintings by Okumura Togyu, 120 by Hayami Gyoshu and 71 by Kawai Gyokudo.

Yamatane Museum of Art

3 Chome-12-36 Hiroo, Shibuya-ku,

150-0012 Tokyo

+81 (0) 47-316-2772

In Kyoto, a new museum opened in 2019 in a stunning location on the river in Arashiyama, near the famous bamboo grove.

Fukuda Art Museum

3-16 Susukino Baba-cho, Sagatenryuji, Ukyo-ku

616-8385 Kyoto

+81 (0)75-863-0606

In Hakone, a popular mountain retreat west of Tokyo near Mt. Fuji, a charming lakeshore museum that specializes in nihonga and holds many works by more recent nihonga painters, including the well-known Kayama Matazo, as well as contemporary artists such as Yanagisawa Masato.

Narukawa Art Museum

570 Moto Hakone, Hakone, Ashigara Shimo-gun,

250-0522 Kanagawa Prefecture

+81 (0) 460-83-6828

In Shimane Prefecture in western Japan, near the charming city of Matsue, a museum perhaps best known for its stunning Japanese garden but also noted for its extensive collection of works by Yokoyama Taikan and many other top nihonga artists. Don’t miss the annex dedicated to contemporary nihonga works selected from top entries to the annual Japan Art Institute (Inten) Exhibition.

Adachi Museum of Art

320 Furukawacho, Yasugi,

692-0064 Shimane Prefecture

+81 (0)854-28-7111