Highway to the Gods: In the Footsteps of Oyama Pilgrims

Mt. Oyama, a peak to the southwest of Tokyo, has long been the goal of pilgrims eager to pay their respects to the gods. Today, visitors can follow in their footsteps on a short, fun trip out of the city.

By Selena Hoy

Fall foliage at the entrance to Oyamadera temple. Photo: Isehara city.

What do tattoos, tofu, and a millennium-old temple have in common? They’re all part of the Oyama Pilgrimage, a religious and social journey to Mt. Oyama that was wildly popular during the Edo Period (1603 – 1868).

A few hundred years ago, the capital city of Tokyo, then called Edo, was booming. Though it boasted a population of one million, the skyline was low-slung and wooden. The distinctive conical shape of sacred Mt. Oyama was clearly visible, rising majestically in the southwest. It looked magical in the sunset, beckoning to the Edokko, the city’s denizens, to visit, pay their respects, and pray in the nature-revering Shinto tradition.

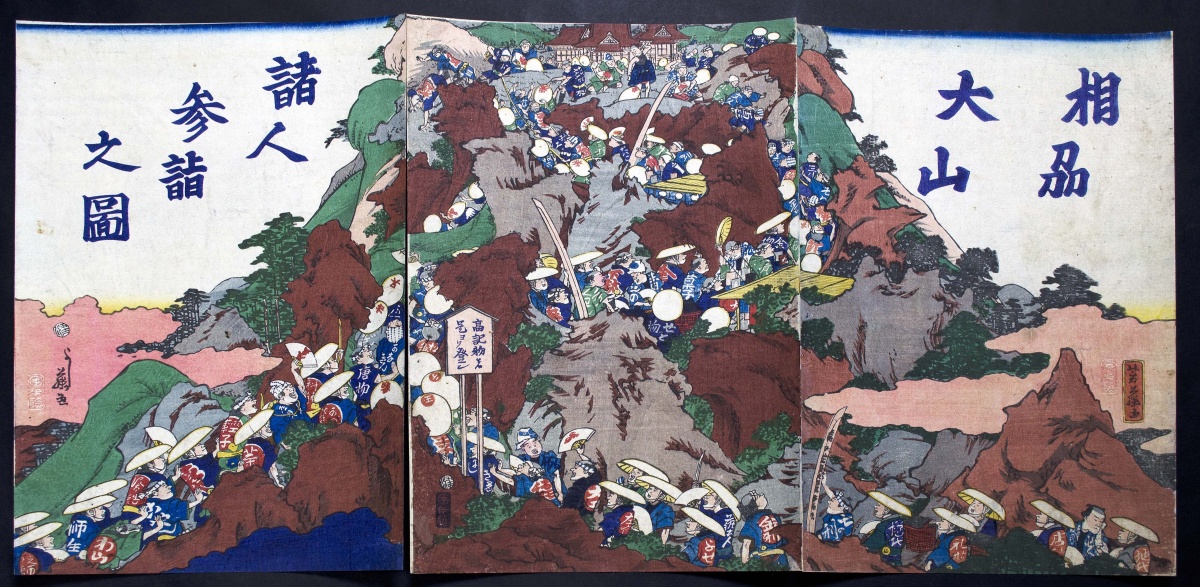

A woodblock of the Edo era, showing the masses of pilgrims ascending the mountain to make offerings to the gods.

And visit they did. At the height of its popularity, 200,000 people, nearly a fifth of Edo’s population, visited Oyama during the several weeks of the annual summer pilgrimage season. Groups of hardy worshippers traveled on foot to the mountain, sleeping in roadside inns over the several day trip.

Another woodblock depicts the colorful tattoos, known as "horimono," that adorned the bodies of many of the pilgrims.

The road thronged with the groups, made up of tradespeople and shopkeepers organized into associations or guilds. They would travel together, wearing matching jackets and carrying staffs. Many were heavily tattooed, as was the fashion at the time, in a style known as horimono. These pilgrims and their colorful body art were a popular subject for ukiyoe artists of the time.

The pilgrimage-related trade along the road boomed as businesses sprung up to serve the pilgrims. Inns and teahouses lined the route, some making nearly their entire year’s take in a few raucous, frenzied weeks. The mountain was covered in shukubo, or pilgrims’ inns, and each would host the same groups year after year.

A typical, tofu based meal at one of the local "shukubo," or pilgrim inns.

The shukubo were typically paid for their services in agricultural products, often including soy beans. Innkeepers would process the beans with the mountain’s excellent spring water to make tofu. Before long, Oyama became known for its tofu cuisine, packed full of healthful nutrients for pilgrims in need of sustenance for their journey.

The people running shukubo were more than mere innkeepers; they also served as pilgrimage leaders, and minor Shinto priests. Each inn had a small shrine where the final leg of the journey would begin, the guides providing spiritual navigation along the way.

Oyama is alight with spirits, and farmers long revered the mysterious mountain, with its rainy, mist-shrouded peak. During drought and famine, they prayed that some of the precipitation that always seemed to linger on Oyama (which was also known as Afuriyama, or “rainfall mountain”), might descend from the heavens onto their crops.

Oyamadera temple in summer foliage . . .

. . . and a night view from temple with lights from the urban sprawl in the distance.

Pottery from the late Jomon Period (2470–1250 BCE), thought to be used in worship rituals, has been found at the summit. Afuri Shrine, which sits at the mountain’s crest, is said to have been established about 2200 years ago, during the reign of Emperor Sujin. A bit below the shrine is Oyamadera, a Buddhist temple established in 755. Over the centuries, warring political factions have muddied the waters of which gods and religions resided where, but one thing has been constant: the belief that this is a sacred place, bathed in rain and crowned by sunlight, with views that stretch across the land and into the sea.

The hike to the peak consists of many rough hewn rock steps. Those looking for an easier approach take the cable cars.

Today, the flood of visitors to Oyama has slowed to a trickle, but the mountain’s magnetic power endures, and some of the old traditions still survive today.

The pilgrimage road then known as Oyama Kaido has become part of Route 246, a major highway that runs from Tokyo to the far side of Mt. Fuji, but vestiges of the popular journey still remain. A small museum in Mizonokuchi, called Oyama Kaido Furusato Kan, displays exhibits related to the history and folklore of the road.

Even today, pilgrims continue to band together, continuing the traditions of the ritual journey. Some groups even bear the traditional full-body tattoos, and carry that art with them to share with the gods (as chronicled in the short documentary entitled Horimono).

Pilgrims take part in a sacred cleansing in the pounding flow of a waterfall in this woodblock print by the artist Kunisada. (Isehara City)

A few dozen of the pilgrim inns are still operating on Oyama. In many cases, they are operated by the same families, maintaining the line for hundreds of years. Tofu has retained its status as the mountain’s famed cuisine, and lodgers load up on multi-course soy-packed meals in preparation for their final spurt. Guides lead guests on the last segment of their pilgrimage: conducting blessings, shepherding them through a sacred cleansing in the waterfall, and helping them complete the last arduous stretch to Oyamadera temple, Afuri Shrine, and the summit.

The view from Oyama Seison Teahouse located at the Afuri shrine. (Photo: Selena Hoy)

And the pilgrims who make the climb can stand at the peak, marveling at the natural wonders Oyama offers, and communing with the spirits residing there. The view stretches from the Izu and Miura peninsulas beyond the sprawl of Tokyo Bay to the Boso peninisula in the distance.

Plan Your Very Own Pilgrimage:

How to Get There:

Mount Oyama is in Isehara City, Kanagawa, and Isehara Station is about an hour from Shinjuku on the Odakyu Line. From Isehara Station, a bus runs to the base of the mountain and the Oyama Information Center.

The Tanzawa-Oyama Freepass is a great deal for those who are visiting Oyama either on a day trip or overnight. It includes a round-trip on the Odakyu Line from Shinjuku, unlimited rides on the local Odakyu Line between Hon-Atsugi and Shibusawa, the local area Kanachu Bus, and with an option to include unlimited rides on the Oyama Cable Car (¥2520 from Shinjuku and including the Cable Car). Local attraction discounts are also available with this pass.

The Hike:

There are a number of trails on the mountain ranging in difficulty, and can easily take up a half day or more of hiking even for strong hikers. For those who want to minimize their hiking, the Oyama Cable Car covers the steep ascent between the Oyama Cable Station at the foot of the hill and Afuri Shrine near the top.

Where to Stay:

Several shukubo are still in operation and accept guests from the general public, including Tougakubou, Kageyu, and Iwae. A more complete list can be seen here. Most packages include a full-course tofu-based dinner. While wild boar is also a local specialty, some inns can also make vegetarian arrangements with advance notice. Oyama has hot springs, and many inns include onsen baths, including some that offer day use (such as Tougakubou).

A recommended break is the stylish Teahouse Sekison at Afuri Shrine, which sells beer, coffee, sweets, and other snacks with an unbeatable view.