Shimbun Nishiki-e: The Meiji-era Origins of Japan’s Lurid Tabloids

In the Meiji Era (1868--1912), some enterprising woodblock artists used their traditional skills to bring a mix of news and entertainment to the masses. These woodblock "newspapers" were the origins of what later became Japan's lurid tabloid media.

By Mark Schreiber"They were called shimbun nishikie (color news sheets), and were illustrated by some outstanding artists of the day."

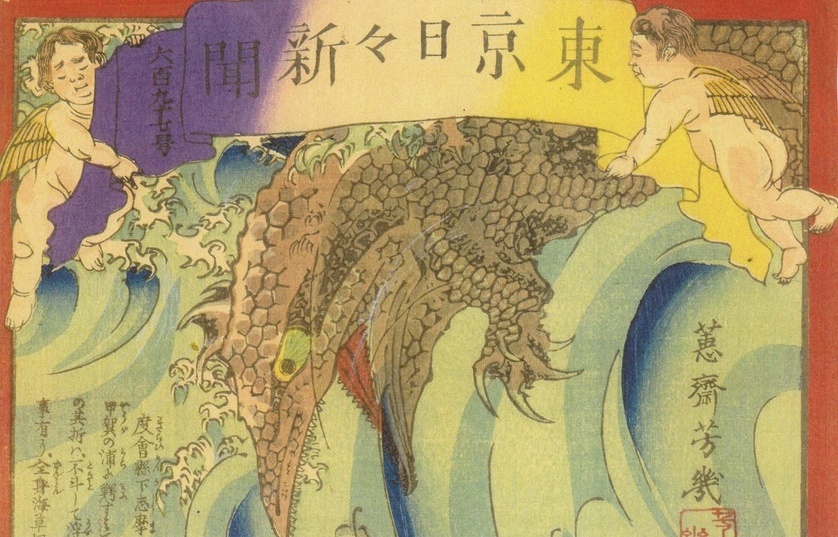

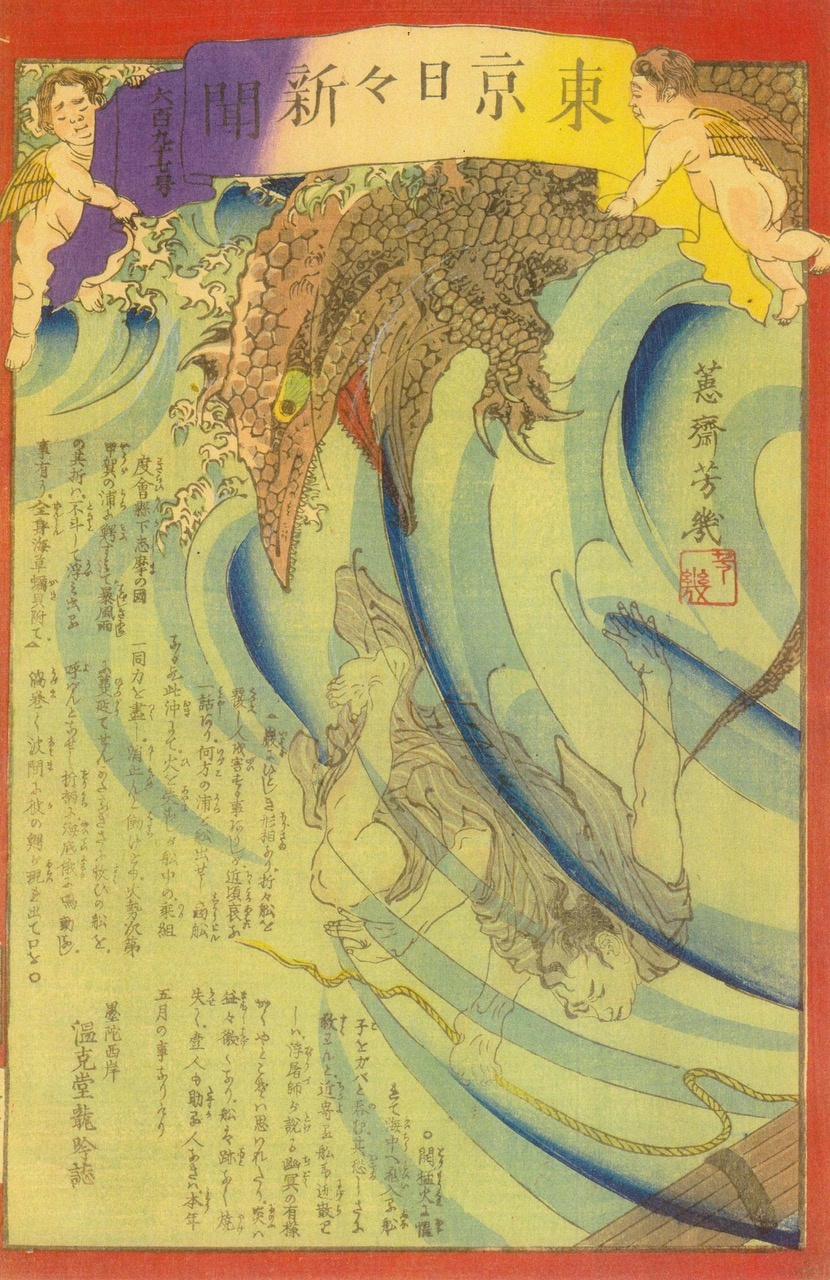

Japanese Jonah: This edition by the artist Yoshiiku was a story of a crewman from a sinking ship being eaten by a sea monster.

With the Meiji Restoration which began in 1868, Japan's imperial government moved from Kyoto to Edo (which was renamed Tokyo, the “Eastern Capital”), and within a short time, almost every aspect of society was beset by major change. In 1871, the feudal class system of samurai, peasants, craftsmen and merchants was abolished. Soon to follow were laws requiring compulsory education for every child.

Many traditional occupations, hit hard by social progress, struggled to find new sources of revenue. Beginning from the summer of 1874, several entrepreneurial individuals came up with the idea of producing colorful souvenirs, single sheet woodblock prints that retold articles that had appeared in conventional newspapers. Along with their graphic color illustrations they featured a readable, narrative style that facilitated their being read out loud to an audience.

These were called shimbun nishikie (color news sheets). Published between 1874 and 1876, they were illustrated by some of the outstanding artists of the day. The two most famous were Ochiai Yoshiiku and Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. Both men had been students of Utagawa Kuniyoshi, one of the most celebrated woodblock print artists of the late Edo period.

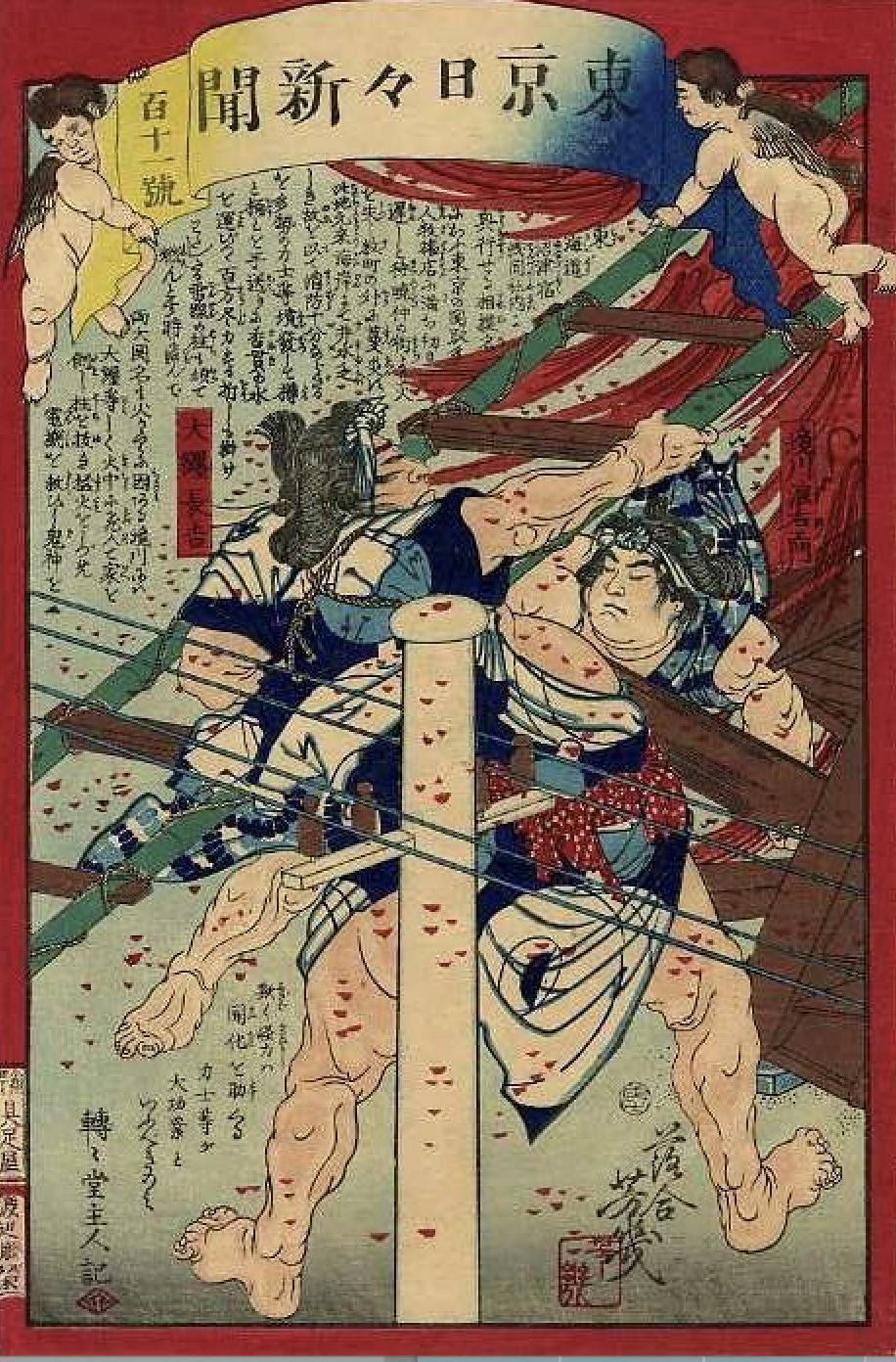

Two muscular sumo wrestlers respond to a fire emergency. With no water, they have no choice but to tear apart the burning structure in hopes of limiting the fire. Notice the utility poles, which were a symbol of the "civilization" of the Meiji times.

Two of the artists, Yoshitoshi and Yoshiiku, gained notoriety in 1866 when they engaged in a friendly competition, each creating a portfolio of 14 prints that mocked historical murderers and other infamous villains as “heroic,” portraying them in bloody scenes. The style of these 28 prints and use of popular gesakusha (writers of minor stories) to provide the accompanying text were almost a dry run for the color news sheets that were to follow in the next decade.

Yoshiiku's Tonichi stories were taken from the Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun newspaper—a forerunner of today's Mainichi Shimbun newspaper. Tonichi is immediately recognizable for its pair of winged cherubs holding up a banner with the publication’s logo, an irreverent poke, perhaps, at Western religious art. They were produced by a print shop named Gusokuya. Each print bore a number, but they were not printed in consecutive numerical order. Their number was a reference to the issue of the newspaper from which the original story was sourced.

The rival Yubin Hochi Shimbun—which today still exists as a sports newspaper affiliated with the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper—was illustrated by Yoshitoshi.

"The text was embellished with puns or plays on words, and written in a style that could be read aloud to listeners."

Rockin' 'n rollin'. A pair of robbers flee when a bride startles them by the sounds of stones they think someone is throwing from the roof. (Yoshiiku)

In terms of style, the subjects in Yoshitoshi illustrations tend to have more expressive faces; his drawings also depicted colorful skies, both daytime and nighttime. The prints can be easily differentiated from Tonichi by the text, which did not flow around the subjects but was inserted within a pinkish cartouche.

In contrast, Yoshiiku prints tend to be more two-dimensional, but project a strong image, almost evocative of Hollywood posters from the silent movie era.

Soon a host of imitators sprang up in other parts of Japan. Prints in Osaka tended to be smaller—about the dimensions of a trade paperback—and were roughly similar in style and content.

Unlike the newspapers on which the stories were based, which adhered to terse and straightforward wording, the text in shimbun nishikie were embellished with puns or plays on words, and written in a rhythmic style that could be enjoyed by either a single reader or read aloud to listeners.

"There were tales of good Samaritans and stories about wrong-doers who ran afoul of the law."

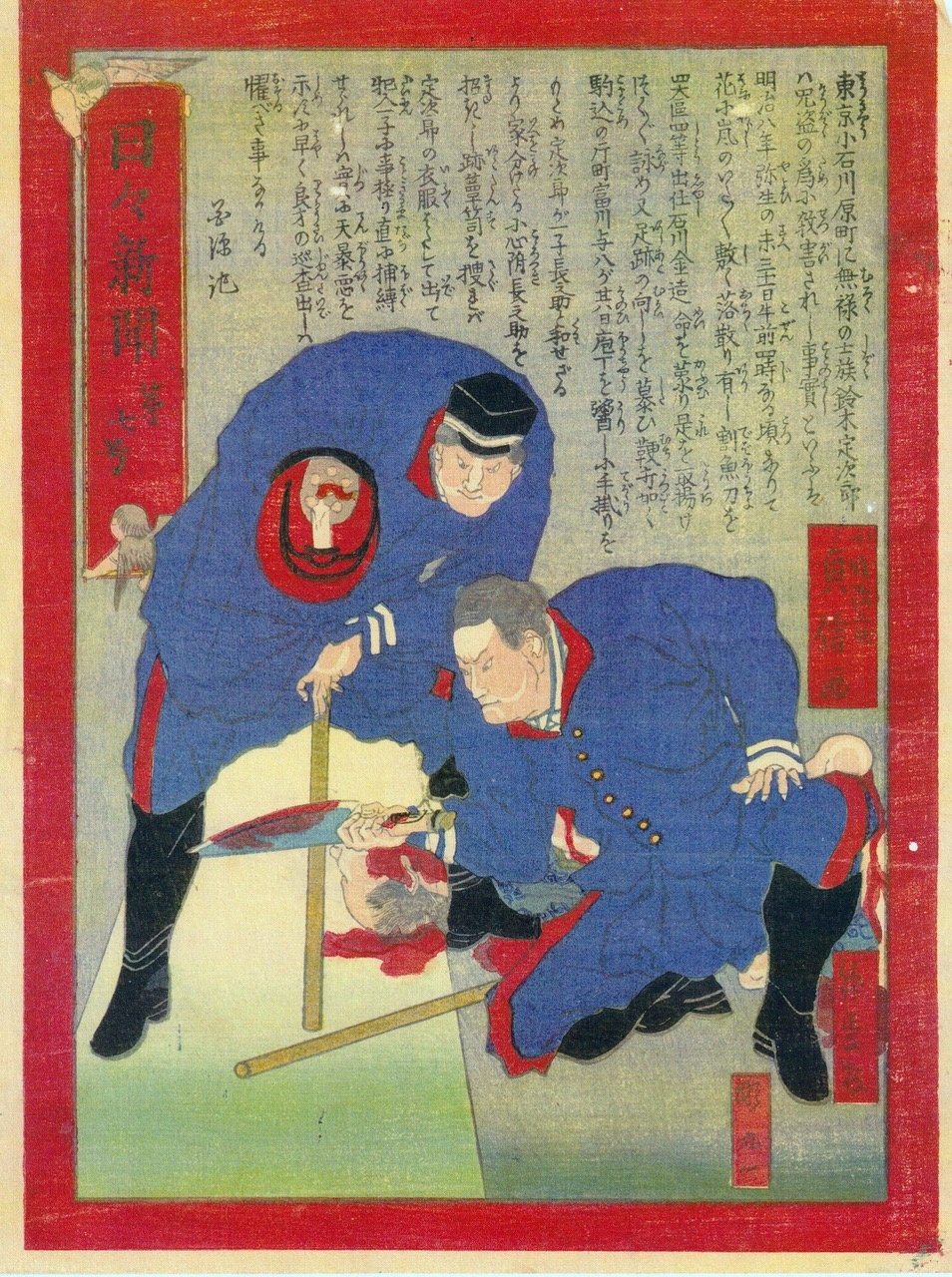

CSI Tokyo: Police examine the scene of a crime in Tokyo's Koishikawa district, following the murder of a former samurai named Suzuki.

The types of news they covered were mostly what passes today as human-interest stories. One Tonichi print, No. 101, the ghost of a woman who had died in childbirth is shown tenderly embracing her sleeping infant during the midsummer O-Bon period, when the spirits of the dead return home. In Yubin Hochi No. 556, the wife of a farmer is praised for faithfully caring for her husband who had contracted leprosy.

The stories also made efforts to convey the moralistic message of kanzen choaku (reward good and punish wrongdoing). These were tales of heroic officials—long a popular theme in Asian countries—who brought outlaws to justice; of Good Samaritans, such as a man who came to the rescue of a suicidal girl attempting to jump off a bridge. Or stories about wrongdoers who ran afoul of the law, to give readers a feeling of satisfaction of seeing them meet their just deserts.

Dysfunctional families were definitely a popular topic, and here's one example of the style of the stories. In Tonichi No. 1015, a gentleman dealt with his wife's infidelity by gift wrapping her and formally “presenting” her to her paramour. As its writer named Tentendo tells it:

A pharmacist selling stomach medicine named Rodayu had a wife so famed for her beauty she had been nicknamed the Kyoto Doll. For some time she had been carrying on a secret affair with a boarder in their house.

When Rodayu learned of the affair, he made a large gift ornament, attached it to his wife's back, and told the boarder, "I've had this Kyoto Doll for many years. Now I give her to you as your toy. So take her."

Upon their eviction from the house, the illicit lovers both broke out in sudden tears and departed, hand in hand.

Yubin Hochi Shinbun. Convicts in the Tokyo workhouse on Ishikawajima island use their free time to learn to read. (Yoshitoshi)

Unfortunately Tokyo has no museum where these prints are on permanent display, but they can be found for sale in art shops along Yasukuni Dori in Tokyo’s Jimbocho bookstore district. They also appear in online auctions. Depending on their condition and rarity, their prices generally range between ¥15,000 and ¥25,000.

Shimbun nishikie are not real journalism and not quite fine art, but appeal to collectors as colorful and unique portrayals of Japanese society during an era of unprecedented change.

To read more on their history and view sample translations in English, visit www.nishikie.com.