Good Reads: "War on Wheels" and Keirin Cycling

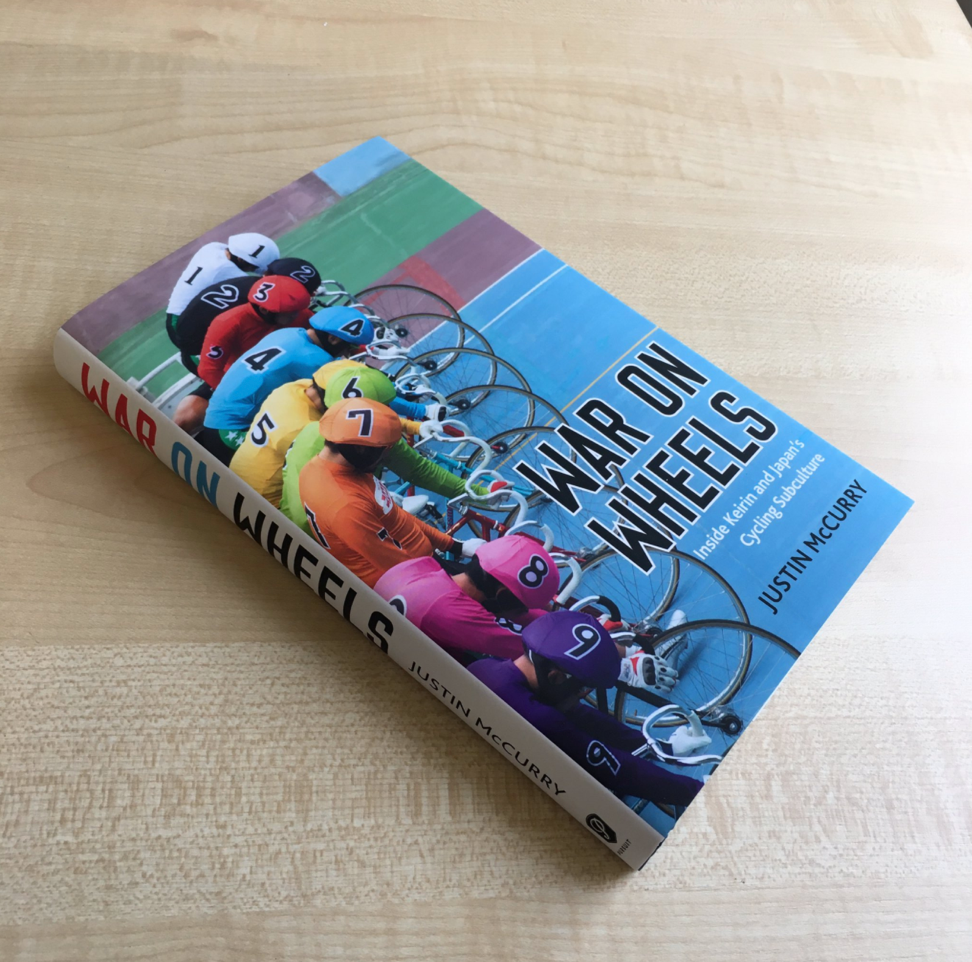

The best books in any genre have something of substance to say that has meaning beyond their immediate subject. Justin McCurry--the Guardian’s Japan and Korea correspondent--has achieved that feat comfortably in The War on Wheels, his exploration of Japanese keirin bicycle racing and the culture around it. (Photo: Justin McCurry)

By Gavin Blair"The competitors have to declare before a race what tactics they will use and even when they will start their final sprint. "

Riders line up at the start of a race at Kishiwada velodrome, Osaka prefecture. (photo: Justin McCurry)

Weaved into the engaging narrative that explains what keirin is, how it works and why it works the way it does, its history, the gambling that underpins it, and who and what the riders and their bikes are, is a series of insights and commentaries on post-war Japan delivered through the prism of the sport.

Like the bikes themselves, the nuts and bolts of keirin appear deceptively simple: nine riders make their way around a banked velodrome behind a pacing bike for a few hundred meters until the pacer pulls off the track with a lap and half to go, which triggers a sprint for the line.

In reality, there are rules on when certain riders can make their move, collaboration between riders from the same region, designated roles depending on seniority and a physicality that extends to moves such as head-butting and shoulder-barging. In addition, the steel-framed bikes have to confirm to extremely stringent standards that ensure no rider has a mechanical advantage, and the competitors have to declare before a race what tactics they will use and even when they will start their final sprint.

"Keirin was launched after the war as a way to raise funds for rebuilding the nation, along with the other three forms of publicly-controlled gambling races: horses, powerboats and motorbikes. "

Women line up for a race at Kokura velodrome in this undated photo. The women’s sport was scrapped in 1964 but revived in 2012, the year women’s keirin also made its Olympic debut. (Photo courtesy Japan Keirin Association)

These elements are essentially what separate Japanese keirin from the version seen in the Olympics and international races. McCurry explains all this in a way that pulls even a non-cycling aficionado into the story, while deftly placing it in the context of Japanese culture and society.

Keirin was launched after the war as a way to raise funds for rebuilding the nation, along with the other three forms of publicly-controlled gambling races: horses, powerboats and motorbikes. The book recounts how keirin developed and sheds light on the ambivalent relationship with gambling that Japan still maintains to this day.

The sport is resolutely working class in a nation that for decades has largely bought into the myth that nearly all of its citizens are middle class. Meanwhile, keirin is barely recognized as a sport and its riders largely ignored as athletes in most quarters in Japan due to the strong association with gambling. McCurry tells of a visit to a bookshop looking for research material on keirin, only to find the little that was available was to be found not in the sports section but in the gambling one. The War on Wheels guides readers through these contradictions into the unique subculture that has been shaped to no small degree by them.

"While the austerity of trainee life does ease once riders turn professional--they can at least then choose their own haircuts - not by much."

Keirin trainees must spend a year at the Japan Institute of Keirin (formerly the Japan Keirin School) near Mount Fuji to qualify for a professional license. Their training regime involves spending a lot of time on rollers. (Photo: Justin McCurry)

All riders seeking a professional license must spend 11 fairly grueling months at the recently renamed Japan Institute of Keirin near Mt. Fuji, a course that prepares them not only for the physical demands of a career that can last for up to three decades, but also for what is expected of them in terms of being a keirin pro.

While the austerity of trainee life does ease once riders turn professional – they can at least then choose their own haircuts - not by much.

One example of this is the way that, in order to eliminate the possibility of race-fixing, riders live together during a meet, essentially cut off from the outside world, with no access to phones or the internet. These are referred to as ‘lockdowns’ in the book, one of a few gentle reminders of how the world has changed over the last couple of years.

Another comes in the description of the keirin school graduation ceremony: “The lecture theatre was a sea of shaved heads, with some faces partly hidden behind white surgical masks, worn habitually in Japan by owners of runny noses who want their public sneezing bouts to be a victimless crime.”

These days of course, such masks need no such explanation for a global audience and have taken on a very different connotation.

"Interspersed with the chronicling of keirin’s evolution are McCurry’s own experiences visiting velodromes as a spectator and punter."

Fans gather near the start line at Hiratsuka velodrome to watch the men’s Grand Prix final in 2017. The winner, Kota Asai, won almost one million dollars in prize money. (Photo: Justin McCurry)

Interspersed with the chronicling of keirin’s evolution, the technical aspects of the bikes and races, and the shifting social and political environments that the sport has negotiated, are McCurry’s own experiences visiting velodromes as a spectator and punter. These vignettes provide a brief but vivid glimpse into the world of the velodrome, and by extension into a slice of Japanese life unknown to many even within the country.

A typical keirin betting slip from a race at Tachikawa velodrome. (Photo: Justin McCurry)

Days after finishing the book I told a friend of more than 20 years about it at a year-end party. He suddenly became extremely animated and told me his best friend since high school was a keirin rider and that he often went to watch him. The fact that I’d never heard about this in more than two decades of friendship perhaps speaks to the peculiar position that keirin occupies in Japanese society. And I’m now committed to going to my first keirin meet with my friend.

(In the interests of full disclosure: I sometimes cover for Justin McCurry when he takes time off his day job at the Guardian, and did so a number of times while he was writing this book.)

War on Wheels: Inside Keirin and Japan's Cycling Subculture

by Justin McCurry

Published by Pegasus Books